Mastering An Entrepreneurial Mindset With Thinking Tools And Coaching

June 25, 2024

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

In this episode, Jeffrey and Dan explore the world of thinking tools and the framework that helps entrepreneurs think strategically. Dan shares the origin story of his first tool and how it evolved into over 240 trademarks. He also touches on the concept of Unique Ability® and its role in his company's success.

In This Episode:

- Self-examination and curiosity play a crucial role in achieving success, but most people don’t make the time for it.

- So, what are thinking tools? Dan provides a definition and examples, and explains their purpose.

- The first tool Dan created, The Strategy Circle®, is still used today exactly as he first created it over 40 years ago.

- Dan has created over 240 trademarked thinking tools since then.

- Jeffrey and Dan explore the origins of Unique Ability.

- Dan reveals where he got the name “Strategic Coach.”

- Dan explains the difference between process, methodology, and strategy. One is more about the outcome, while the others are about the steps to achieve that outcome.

- Dan divulges what motivates all of his personal and professional endeavors. (Hint: It’s not money!)

Resources:

Learn more about Jeffrey Madoff

Dan Sullivan and Strategic Coach®

Book: Your Life As A Strategy Circle by Dan Sullivan

Episode Transcript

Jeffrey Madoff: This is Jeffrey Madoff, and welcome to our podcast called Anything and Everything with my partner, Dan Sullivan. Today we're, for a change, going to be talking about anything and everything. So welcome to the podcast. And today where I wanted to start off is tools, primitive man opposing thumbs, you know, all that sort of thing. And Dan, one of your distinguishing and unique abilities is the creation of tools in terms of what you've been doing with Strategic Coach over the years. And I'd really like to do a dive into that today in terms of where that came from and the whole origin story of the tools. But I'd like to start with you first telling us, how do you define tools and what you do?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, first of all, I'd like to modify my kind of tool, and I call it a thinking tool. And it's generally a series of questions, four or five levels of questions on a sheet of paper, and I have them diagrammed. You know, they're kind of matrixy. You know, you have a series of boxes, but they proceed in a systematic way. So for example, the very first tool I created was in 1982. I was a one-on-one coach in those days, Jeff, and I had coached over since ‘74 to ‘82. Eight years, I probably coached about 60 or 70. And at first, I wasn't clear that entrepreneurs were my target market. I had politicians, I had corporate people, I had people who were in foundations, nonprofits, and everything else. But very quickly, within three or four years, I realized that entrepreneurs were the type of person who, if they liked it, they could make the decision on the spot and they could write a check on the spot because I took up-front fees to make my receivables a little easier. That was after my second bankruptcy, I adopted that principle. But the tool that I came up with was called The Strategy Circle, and it's based on a formula which supports almost all the tools, and it's VOTA. You ask a person a vision of a point in the future, and usually I use something like three years. So if it's three years from today, and we're having this discussion three years from today, and I name the date. So the date were a particular date in 2024. So I had mentioned the same date in 2027. And then I said, what has to have happened in the three years, we're in the future now, we're in 2027 and we're looking back to ‘24. What has to have happened in your life, both business and personal, for you to feel happy with your progress? Okay. You know, they had agreed to have the conversation, so that was a given. And then what I would do, as they would talk about things, I'd write them down. First of all, in the old days, on a flip chart. So I'd have flip chart sheets taped to the wall, and one of them would be vision. And we talk about it, they might have 10 things up there and I'd say, okay, let's just circle the five top ones. If you get the top five done, you'll probably get the other five done too. I tried to get them to put numbers, you know, it's a quantitative goal where you have a bigger number, it's a qualitative goal and it's marked by an event. Okay. So, you know, if I'm working with Jeff Madoff, and it talks about his current play, you know, and this is 2018, there were steps upward that you've already achieved, like the, we have to have the workshops in New York, we have to open on the road in Philadelphia, we have to have a major run in Chicago. And those aren't quantitative, but they're qualitative. They're events, you know. They happened. You've got witnesses that they've happened. So I'd get them, and then I'd stop, and we'd have coffee or something. We'd chat. And then I'd go on to the next step, and I said, tell me everything in the present that opposes you getting there.

Jeffrey Madoff: So obstacles.

Dan Sullivan: Present obstacles, yeah. And my proposition here is that you don't even know you have the obstacles until you know you have the goals. Okay, the goals actually create the obstacles. I'm very positive towards obstacles, that the obstacles your brain comes up with when you present itself with a goal that you can't achieve right now, you don't have the capability and the resources right now to achieve it, you don't really know that until you have the goal. You don't know what kind of obstacles you have. And then they'd brainstorm the obstacles, and then I said, well, eight will do. I don't know why I picked that number, but eight, I find eight really works. And then I'd say, now, let's take each of the obstacles and consider them raw material for achieving the goal.

Jeffrey Madoff: Okay, and by the way in your calling your first tool with the V was vision was the O obstacles?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Vision, obstacles, and then you transform the obstacles into decisions, into communications, actions, and achievements. Okay, so you would say, so how does this obstacle get transformed so that it ends up with an action? So it's vision, obstacles, transformation, action. We use that tool today, so it's 42 years later, and we do it exactly the way I did it the first time I did it. It's a very durable tool. And so we start off with people doing a particular project of theirs, and then pretty soon they have the tool, they have the capability of doing this for themselves. Okay, so with all of our tools, we're giving them a structured way of thinking about something, which then becomes their capability with repetition. And I have 240 of them, and they're all trademarked.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, which is incredible. So talking about your first tool, and this probably applies to all of them, would you call it a strategy for achievement or would you call it a methodology in order to achieve?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I would say it's a process for achievement. It's kind of like an algorithm. In the Patent Bureau, they have a requirement that what you have is an algorithm. And an algorithm is a series of steps that produce a predictable result. In other words, if you do this, and you do this, and you do this, and you do this, you can predict that it'll be a particular type of transformative. And they use the word transformative result. But you're doing it in a way that is non-obvious. The Patent Bureau actually has a term called non-obvious. That if you looked at the sheet up front, it's not obvious where this leads. Yeah, because then it's just common knowledge, and they don't patent common knowledge.

Jeffrey Madoff: Is there a difference between a process, a methodology, and a strategy?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I think the words are different. I mean, you could look them up and compare them, but I think process and methodology are fairly similar. And I think a strategy is more of a contextual than it is content. Well, let's use your theater example. A strategy would be that you have the workshops so that you'll get the media in for the first time and you have the investors in for the first time, potential investors, some existing investors and potential investors. And if that works, then we have the ability to go on to a first opening. And usually it's not in New York, it's on the road. And Philadelphia is famous for being a good opening city, big city, close to New York. And then if we do that, and then we package it, we have videos of the performance, and we package that it actually exists, and, you know, someone can watch three or four minutes of the actual play, then you have a good chance of going for a longer run, you know, for dollars, really for dollars in a major city. So I would call that a strategy. I mean, the next step that's being discussed right now is that it goes to the UK, and in the UK, if you open at a really top-notch regional theater, the chances are good that you would open in the West End of London. And that's just a sideways jump from West End and London to Broadway. So that would be a strategy. I think if you said any one of the three words, people would know what you're talking about. Well, it's interesting though, because you also, and I don't even know this, this is also—no, no, and I haven't been asked the question before, so I'm going to ask Perplexity, the AI program. What's the difference? What are the main differences between strategy, process, and method?

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, well, you know, I think that the strategy is a plan that hasn't yet to be executed. And the methodology, you know, is the action. But you named your company, and I've never asked ...

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: And I've never asked the question. Was it always Strategic Coach?

Dan Sullivan: You know, it's a really good question. I think if I'm not mistaken, it happened in the ‘80s. I had started coaching in ‘74, so it happened in year 13. And I did house calls in those days. I went to somebody else's office, you know, and it was quarterly and it was one-on-one. I walked in and my client had somebody in the room with him. He said, I'd like to introduce you to Dan Sullivan. He's my coach, my strategic coach. And I had never said that, but I said, bingo. We called our IP lawyer and about three days after that, then we had Strategic Coach because it's easier for someone from the outside to see it often than to see it from the inside. First of all, it was not untrue. I think that's the role I was playing. And strategy, for me, is you have an outcome in mind. Strategy is more about the outcome that you're shooting for rather than the means by which you get there. And I would say that strategy probably comes first.

Jeffrey Madoff: I think so, too.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I think successful Broadway play is the strategy.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes. Well, that's the goal. That's the goal. But it's interesting, I didn't know, it just occurred to me, that I had never asked you before, and I've never heard the story behind, well, originally I was, what did you call yourself? Just to cover it.

Dan Sullivan: It was just Dan Sullivan, you know, I had Dan Sullivan, consultant, you know. You know, when you're dealing with business cards at $50 for 500, you're not as choosy, but probably. Yeah, I had my address, I had my phone number, didn't have email in those days, that was it. But it becomes very important to name things. I draw people's attention to the book of Genesis, the first book of the Bible, and the first human skill that God gave Adam, the task of naming all the plants and the animals in the Garden of Eden. You think God was just messing with him?

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I don't know.

Dan Sullivan: So I tell a story about that. I said, you know, it's the sixth day, you know, and they've just about got everything named. It's the sixth day because seventh day is a Free Day, sort of. And anyway, they're just leaving and God points, and he says, what's that? It's a very slow moving animal coming down a path. And Adam looks at it and he says, I don't know. It kind of looks like a turtle, God says. That's what it is. That's what it is. And I tell that joke, and some people get it about five days later. You know, they laugh five days later. But everything's made up.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes, yes.

Dan Sullivan: And naming is one of the ways we make up things.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. Absolutely.

Dan Sullivan: It's like the play Personality. You named it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, that's right. You know, I mean, I wonder. Did you name it? Did I name it?

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. If you recall, that was the second name. The first name was Lottie Miss Clottie.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: Which was Lloyd's song that started it all. And then we realized that, you know, Personality’s got a double meaning. Plus, it was his biggest hit.

Dan Sullivan: It's a perfect name.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, yeah. But it took us a bit to realize that. And when we were first promoting it, doing our first reading, all the posters and everything was Lottie Miss Clottie. Then we changed that. But, you know, it's interesting. I love this story because I also think when God gave Adam all that sort of cataloging work to do, you know, it's also he might have just been concerned that Adam would be consumed with having sex, and how can you get him to do anything else? So you just got to give a bunch of tasks and create some sins in there, so they'll get the work done.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, there's a lot of mystery on how the whole thing got started. I mean, do you ever see any videos or read anything by Richard Feynman?

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, yeah. Yeah. Brilliant guy.

Dan Sullivan: He was on the atom bomb project when he was in his ‘20s. I may have recounted this to you, but he was on the BBC and I was in a very sort of snot nose, snooty BBC, clearly very, very biased in terms of the subject matter. And he says, Professor Feynman, you know, the origins of the universe, you know, many people, of course, traditionally believe that, you know, the biblical tale of God creating the heavens and the earth. But he says, you know, in the last hundred years or so, we've become pretty convinced that it was the Big Bang. It was the Big Bang that created the universe. And he says, so what are your thoughts about that? And Richard Feynman says, you know, I've given a lot of thought to that. And he says, you know, when you look at both sides and you weigh them, he says, you know, I've really thought it through. And he says, I feel you just have to come down on the side of God creating the universe. He says, the Big Bang, he says, is so ridiculous. He says, who created the bang? And so, yeah, it's really, really interesting. But what my goal is with my tools is that people think about their thinking. If I create a value proposition inside my coaching is that if I ask people questions that relate directly to their aspirations and it relates directly to their experiences and give them a structure to actually record what their answers are, they're very creative. They become very, very creative when you do that. It's the sort of questions that they can't ask themselves. They have to be presented and be kind of in the spotlight so you're asking them the questions. And so I have one that I just created about a week ago. I tested it about three times and it was a real winner and it was called, very Euclidean. I was very, very impacted by Euclid, the Greek mathematician, 300 BC. who, I don't think he was an innovator, but he was an aggregator. And what he did is he pulled together in book form all the known mathematics. So the Middle East at that time, Middle East was the center of the world in those days. His first book, Our Proposition, so I put out a proposition in my tool. It's called Confident About Your Past. And I put out a proposition that you can't create a more confident future until you first create a more confident past. That's the proposition. And then I have four columns, and one of them says, last year, last quarter, last week, yesterday. So what I want you to do is brainstorm, and I'm going to give you 90 seconds for each of the columns. And the 90 seconds is, what are you most confident about the last 12 months, last year? And they write that. Then 90 seconds, what are you confident about the last quarter, confident about the last week, and what are you confident about yesterday? Very, very interesting what happens. Because if you had just asked somebody what was the last year like, they would probably start off with the things that didn't work. Okay. You know, up and down and everything else. But the exercise here only allows them to identify and record and then share, because they go into breakout groups and they talk about it. And then they're very, very high. You can tell the confidence level in the room goes up as a result of the exercise. And I said, let's go a little further, and let's take a minute. And with each of the columns, identify the top three for last year, last quarter, last week, and yesterday. And they do that, and you can tell the energy ramps up another level. And then you say to them, now write down your three biggest insights that you got from doing the thinking above. And they write down the three insights. Then they go and talk about this, and they're as high as a kite when they come back from the conversation. And by answering the questions, they've changed their past, which allows them to change their future.

Jeffrey Madoff: This is fascinating for a number of reasons. And by the way, I wanted to just give you a nod for getting us back on track again. That was a great segue as we were going spiraling into biblical times in the origin story of the universe. It all relates. It all relates, because it's anything and everything.

Dan Sullivan: We've given blanket forgiveness beforehand. Naming's important.

Jeffrey Madoff: So Strategic Coach, the name came about because actually one of your clients kind of just calling that out and it somehow resonated. And what you have done, every time you've talked about a tool, if they start off with eight things, you have them get it to four. So there's a reductive aspect to it, which is really smart because those eight things may be overwhelming, but four become manageable.

Dan Sullivan: Three actually. Yeah. I mean, I had four, I started with four and then you get down to three. But when they brainstorm up above, they might have 25 things.

Jeffrey Madoff: Exactly. Exactly. So you create a methodology of reduction so that the task isn't so overwhelming that they can't get their arms around, what do I do next? You know, that kind of thing. which brings me back to another core thing of Coach, which is Unique Ability. When did you understand and how did you come to understand the concept of Unique Ability? And what is your, I think I know it, but what is your Unique Ability and how did you land on that?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, two questions. I'll go after the origins first. Actually, it happened in 1980 because, you know, my goal was to be a coach, but every 30 days you make sure that you can pay your bills. So I took a side job, and it was someone that I got to know in Toronto who ran for Parliament, the Canadian federal government, and he won. And he won in 1980. And he was immediately appointed by the prime minister at that time, Pierre Trudeau, the father of the present prime minister. And 1980 was the United Nations Year of the Disabled and the Handicapped. So the United Nations has designations for this year is about this, and it's trying to focus people's attention on a major issue that needs solutions. So I was hired as the writer of the report and also the artist, because I'm a layout artist and a writer. That comes from my advertising agency days. So we went around the country for about four or five months, and my job was to interview disabled and handicapped people. And then to have them photographed to the degree that they allowed that. So we were going back and forth by jet, government jet, across the country. And I was just pondering after I'd done about 15 or 20 interviews. I said, you know, these people are sort of disabled and handicapped in a very visible way, in a very obvious way. But I said, I'm sort of disabled with lots of things. I'm sort of handicapped. You know, if it's real detail work, you know, I have to really keep track of details and things like that. I'm sort of disabled, you know. I can maybe do it for three hours, but I can't do it for three weeks. You know, I am good at some things, which I can do every day, and it gives me energy, but there's a lot of activities, follow-through work, detailed work, any kind of bureaucratic work. You know, it just tires me out and I'm really no good at it. And you wouldn't hire me for that. You'd interact with me for an hour and say that disqualifies you from about 90% of activities. But what was really interesting, Jeff, is that the majority of the people that we interviewed had actually normalized their lives. In other words, they had a job out in the general population. They were leaders of things and everything. So this wasn't the usual handicapped or disabled person. You wouldn't see that person, and they wouldn't give you permission to interview them. So by its very nature, the fact that they agreed to an interview, they had already declared independence from their handicap. They had already declared independence from their disability. And then I started to identify that the thing they shared in common that was positive was that they owned their situation and just decided to normalize their lives out in public. So I said, there's a sharp distinction between where you're disabled and where you have something unique about you that you're just capitalizing and maximizing what you're actually great at.

Jeffrey Madoff: And how did you then land on what you were?

Dan Sullivan: I kept going back and forth of, you know, I can't do this very well. I'm sort of incompetent here, barely competent here. So I might have a above average skill here, but it doesn't really interest me. You know, I wouldn't commit my life to this. I'm a good writer, but I wouldn't make my living writing. I don't make my living writing. I use writing to support the coaching program, but I wouldn't agree to be a writer for someone else even though I was at the ad agency, and I'm a good enough artist that I can present my ideas to a finishing artist so that they can do a really good job. But I just began to see, and then I established a proposition that everybody's born with a Unique Ability, but most people don't have the proper surroundings, they don't have the proper support to actually build their life around their Unique Ability. They're educated to sort of fit in and do what other people want them to do.

Jeffrey Madoff: So was this, though, a lightning bolt idea?

Dan Sullivan: Oh, yeah. This is the central idea of Strategic Coach. This is the cornerstone of Unique Ability. Again, there's a tool where people can think this through.

Jeffrey Madoff: And how far into Strategic Coach were you before you came up with the notion of Unique Ability?

Dan Sullivan: Well, the activity of coaching, I was 10 years in. I mean, I was coaching going back there. So that was 10 years in. And then before it became, well, we didn't have the Program then, it was just me doing one-on-one coaching. So it didn't really play a part in The Strategy Circle. The one I described to you became the central activity. But the moment we started The Program and we had workshops filled with people, starting off with 20, 25 people, now we have 50, 60 people in the workshop. You start looking for unifying concepts that everybody is working and Unique Ability is number one.

Jeffrey Madoff: Would you have ever imagined during those first 10 years what coach would grow into?

Dan Sullivan: No.

Jeffrey Madoff: How did that happen? Was there an overall strategy with an outcome that you wanted or was it kind of an organic thing and you were able, just like you're able to discover Unique Ability, really through self-examination?

Dan Sullivan: And experimentation. Yes. I mean, you do a lot of R&D, you do a lot of trial and error. I would say the biggest game changer was meeting Babs. Because Babs runs the company. She's got a phenomenal ability to put together great teams. And so the rule, we met in ‘82, actually about three weeks after I created The Strategy Circle, we met. And then in ‘86, I think it was ‘86, late ‘86, early ‘87, she had her own business. And she said, you know, I think the business you have with this coaching is going to be big. And she said, why don't we just team up? I've got to free you up from a lot of stuff. So my job will be to start building teams around you so that you're freed up, so that you can just do, well, one, what brings in the bucks, but the other thing, what I can clearly see you love doing. So I think the real clarification of Unique Ability really came from the interaction between Babs and me, where she was saying, free up Dan. What you have to do is free up Dan. To this day, it's the central commandment. Whatever you do, free up Dan. Dan brings in the cash.

Jeffrey Madoff: So an interesting thing is, you talk about 10x-ing your business. You talk about having rent to pay and all of that. On the other hand, and we've spoken over time quite a bit at this point, I've never actually heard you reference the income. I've always heard you referencing the process, the curiosity that drives you, the passion for creating new tools, and all of that. This is a long way of asking, is the goal money, or is money the byproduct of doing something that is good and desired by those willing to pay for it?

Dan Sullivan: Well, the way I look at it, money is the scorecard. It's the scoreboard. The creativity is the game on the field. Every once in a while, you glance up and see what the score is. But I'm not driven by money. I'm driven by creativity and growth.

Jeffrey Madoff: And so is the metric for growth?

Dan Sullivan: Money. I mean, it's one of them. Right.

Jeffrey Madoff: We were talking before, we won't mention names, unless you want to.

Dan Sullivan: People's names shall not be mentioned.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes. You know, people who clearly their goal is money. And you know, when that's solely your goal, you can pretty much rationalize any action that you take if that helps you achieve that goal. So if somebody, like the people we were talking about, if somebody has achieved the goal of making a lot of money, yet the way they've done is either through deceptive practices, taking from others or so on, how good of a metric is money for that? Well, I mean, ethics question, you know?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Yeah. I mean, I think there are people who have good character and money is their big thing. And there are people without character and money is their big thing. You know, and it's hard to tell, you know, from the outside what's the central motivator for anyone? Mm hmm. You know, I don't really know what motivates people. I know there's something that motivates them and maybe it'll be revealed and maybe it won't be. I mean, I think one of the reasons why we're attracted to each other, I think that what motivates us is very resonant.

Jeffrey Madoff: I agree.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. I mean, I don't see where there would be any ending to our conversations. I don't see where there would be any ending to our collaboration, you know, in our creating things. So you do that. But I think that's a character issue. You know, I like being useful and I don't like being use-ful. That's a result of disadvantaging other people.

Jeffrey Madoff: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. And I think that, you know, what you and I share is curiosity in a very, very broad sense and the ability to drill down in a very specific way.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And I think we admire execution. You know, we admire getting things done. You know, having a vision and see it become a reality.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, yeah. Yeah. So you've established quite a tool kit. Have you ever thought of, this just occurred to me, but have you ever thought of really focusing on that, whether it be a book, I know it's of course a day-to-day of Strategic Coach, but you know there's so many people that would benefit from what you're doing, and you said 415 tools at this point?

Dan Sullivan: It's probably a little bit more than that, but that's what the ones we have logged in for the trademark process.

Jeffrey Madoff: So, is your Unique Ability creating tools?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: But for entrepreneurs.

Dan Sullivan: Right, tools for entrepreneurs. Yeah, for successful, talented, ambitious entrepreneurs. No, and that's it. No, I mean, you just put your finger on it. That's my Unique Ability.

Jeffrey Madoff: Is it creation of tools for thinking tools for ambitious entrepreneurs, talented, successful, ambitious, who are seeking greater personal freedom?

Dan Sullivan: Right, right.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. Where did the tools come from? What's the origin of a tool?

Dan Sullivan: Well, the thing you start with is that your brain uniquely operates in a particular fashion. You know, you mentioned curiosity. It's what you're curious about that really determines your originality. I think all creative people are curious, but what's the nature? I mean, what is the thing that you're curious about? Okay. And I'm curious about how entrepreneurs, practical creators of things that get things done. The original definition that I can find of entrepreneur comes from a French economist, before there were economists, in 1804, and his name is Say, S-A-Y, Jean-Baptiste Say. And he said an entrepreneur is someone who takes resources from a lower level of productivity to a higher level of productivity. And he was asked the question, well, what kind of resources? And he says, any kind of resources that other people will pay for. It just struck me that it's as true today as it was in 1804. And it just struck me that this is what makes the world work.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, it's also what ignites you, I think, to make the world work, is a compelling need, and I share the same need, a compelling need to create, to do something that reaches out to that audience.

Dan Sullivan: It hasn't been done before.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. And then the challenge becomes refreshing, yet keeping it unique, and keeping it coming from that same well, as opposed to as some people do, plagiarizing from others. So as original as thought can be, because same ideas can occur to different people in different places at the same time, but that compelling need to create is, my sense is, you have built a business around and what supports your compelling need to create.

Dan Sullivan: That would be totally correct.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I mean, it's fascinating because you also, the earlier on your vision, obstacle, transformation, action, you've kind of done that about yourself, the result being those are the strategic steps to enact in the methodology that creates new tools that makes strategic coaching a unique proposition value-wise for entrepreneurs.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, there's a drawing by Escher, and it's two hands drawing each other. And I think it's kind of like that, that you kind of create your next level of capability, and that level of capability allows you to create the next level of capability, and then it goes back and forth. You got to always be dealing with new material. Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, and what strikes me, though, is as fascinating is, in order to achieve what you've achieved, you've got to put yourself through it first. And that's part of, of course, the trial and error. But without that self-examination, which is something, by the way, I think an awful lot of entrepreneurs, an awful lot of people, not just entrepreneurs, don't do.

Dan Sullivan: That's right.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, you know, which is kind of fascinating.

Dan Sullivan: I think it's not a function of intelligence either. I call it thinking about your thinking, that you're aware that there's an activity that's going on inside of you all the time that's observable. And most people I think only come in contact in a crisis. Something bad happens and all of a sudden, like 9-11, I noticed people were very reflective after 9-11. I came to New York about a month afterwards and we did a big event at the Four Seasons on 57th Street. We had about a hundred from the surrounding areas, maybe five states. And they came in, we maybe had 80 or 90 there in those days. And I noticed people were enormously reflective. And I noticed walking the streets of New York, people were nice to you. But it didn't last. It didn't last. But it caused such a shock to people's systems that they started seeing things in perspective. And I had a great story. I had one client that was in one of the World Trade Center buildings. He was above where the jets hit, so he would have died. 87th floor, 90th floor, something like that. And his secretary sent him out to New Jersey that morning, but it was the wrong day, and he got out there and he called her, and this is before the jets came, and he just reamed her out. You know, you're wasting my time. And then she got so upset when she put the phone down that she got on the elevator and went down to the concourse, the shopping concourse, to get a coffee because he wasn't going to be back. And the jets hit about 20 minutes after she got down to the bottom floor. And then they couldn't get in contact because, you know, the phone systems were just overloaded, you know, after that. But they finally got in contact with each other at around seven or eight o'clock at night and they forgave each other.

Jeffrey Madoff: And of course, you have to be alive and present in order to do that.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Yeah. But it was really interesting. I think most people are really forced to confront the way that they think about things that I think is actually the natural activity of people who are really creative. That you're always going back and forth between the creator and the thing that's being created.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, and, you know, part of the process of that is, you know, it's necessary to get feedback. And, you know, the feedback on the play is the laughter, the applause, the silence when people are just, you know, as director Sheldon Epps said, that's the sound of people listening. And, you know, that sort of thing. Well, the tools that you have created are the result of not only the self-examination, but the thousands at this point of entrepreneurs you've spoken to, the obstacles that maybe they haven't recognized yet that you have, that you can give them the tools to work on that. And I find that whole process of discovering one's own Unique Ability, and then how do you actualize that? You know, how do you do that? Because it's also hard, you know, you are both, on one hand, gregarious in front of your audiences and all of that. On the other hand, you need a lot of alone time to do what you do. Because if you're not ever alone, you can't hear those voices that can, you know, help you discover those things that need to be done for what you're trying to express.

Dan Sullivan: I think there's a time when you're young where you realize that you're different. We have similar time period, the ‘40s, early ‘50s, you know, in Ohio. But can you remember, you know, a time when you just sensed that this is not the way other people are?

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. And that was in some of my classes. It was interesting. Classes where I had a lot of questions, sometimes because I couldn't see the value of the class. You know, I was in third grade and Mrs. Turney came in with her art cart and wearing her robin's egg blue smock. And, you know, she was really disciplined, a real disciplinarian. And I was drawing at that time, Davy Crockett, if you remember, Fest Park, Davy Crockett. And I was drawing pretty detailed pictures of the fight at the Alamo. And my classmates really loved the pictures and wanted the pictures. And I loved doing them. And it was fun. And so she comes by and she wants me to do crayon resist. You know, the wax on the crayon would not take the liquid. So when you put watercolor on top of it, it gives you some piece of crap that you can't control the outcome. And so she said to me, what are you doing? I said, I'm drawing. And she said, why are you drawing that? Well, because I want to. And … got a market. Yeah, I got a market. What's the matter with you? She said, you do the assignment. And I said, Yeah, well, I don't wanna do that. I wanna do this, and this is art class, so why can't I do that? And she said, you either do what I tell you to do or you sit there with your hands folded for the rest of the period, which is exactly what I did. But then I had a fourth grade teacher, Mrs. Ripley, who I actually acknowledge in my book, who encouraged questions. And all of a sudden, I felt so engaged in the classes because it was, well, Jeff, what do you think? You know, and she would ask other students and she encouraged dialogue. She encouraged you to think about things and it was wonderful. So yes, I realized very early on because certain teachers would get really angry with me because I would ask questions or question something. So then jump ahead literally 50 years. My daughter comes home from school, you've met Audrey, and she was sent to the office, kicked out of class. This was like actually in like third or fourth grade. And she was kicked out of class because the teacher said, no more talking. Anybody who talks is going to get a demerit or whatever it was. And so she said, turn the page, whatever. And Audrey said to the girl sitting next to her, what page did she say? Teacher tells Audrey and the girl to stand up. And she takes them out of the class into the hallway. And then you start hearing the noise in the classroom. And teacher said to Audrey, Audrey, I told you no talking, I told you both no talking, you're going to have to leave the class. Now we're out here because you have disrupted the class. What do you think of that? And Audrey said, I think it's more disruptive for you being out here in the hallway because listen to all the noise in the classroom. All I did was ask what page we're supposed to open the book to. And teacher kept her out of the class the rest of the day. And so Audrey told me what happened. We got a call from the school and Audrey told me what happened. And I just kind of smiled and I said, well, you were right. You were right. And yes, it was more disruptive for the teacher to be out in the hall, bawling you out for nothing while that's going on. So I am big on respect and decorum and all of that. But there's also times when It doesn't apply. And of course, Margaret, my wife, said, well, that's your side of the family in that situation.

Dan Sullivan: Mine was just in first grade because I had grown up without other children. I grew up on a farm, and just because of the birth order in my family and where we lived, I just had my siblings, and they ignored you because you're younger. So I really, really learned how to talk with adults, starting with my mother, you know, my mother. And my mother was really good for me. I think I'm her vicarious child. She was born in 1910, a female, and what a boy born in 1944 could do out in the world was drastically, and I think she encouraged me a lot in the direction to be who she wanted to be. She gave me a lot of freedom. She gave me a lot of time to talk with her, ask questions and everything like that. And then I started doing it on other adults, you know, asking the questions of other adults. And I had a killer question when I was, I don't quite remember when it was, but it was early. I would meet someone, you know, and I'd say, when you were my age, what was happening in the world? And they'd talk, you know, they'd talk. And then you didn't understand something, then you talked about that, and then they'd talk some more, you know. When I got to first grade, what I found out is the other six-year-olds didn't know anything. You'd ask them a question, they didn't know anything, so that was a waste of time.

Jeffrey Madoff: Thanks for joining us today on our show, Anything and Everything. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend. For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

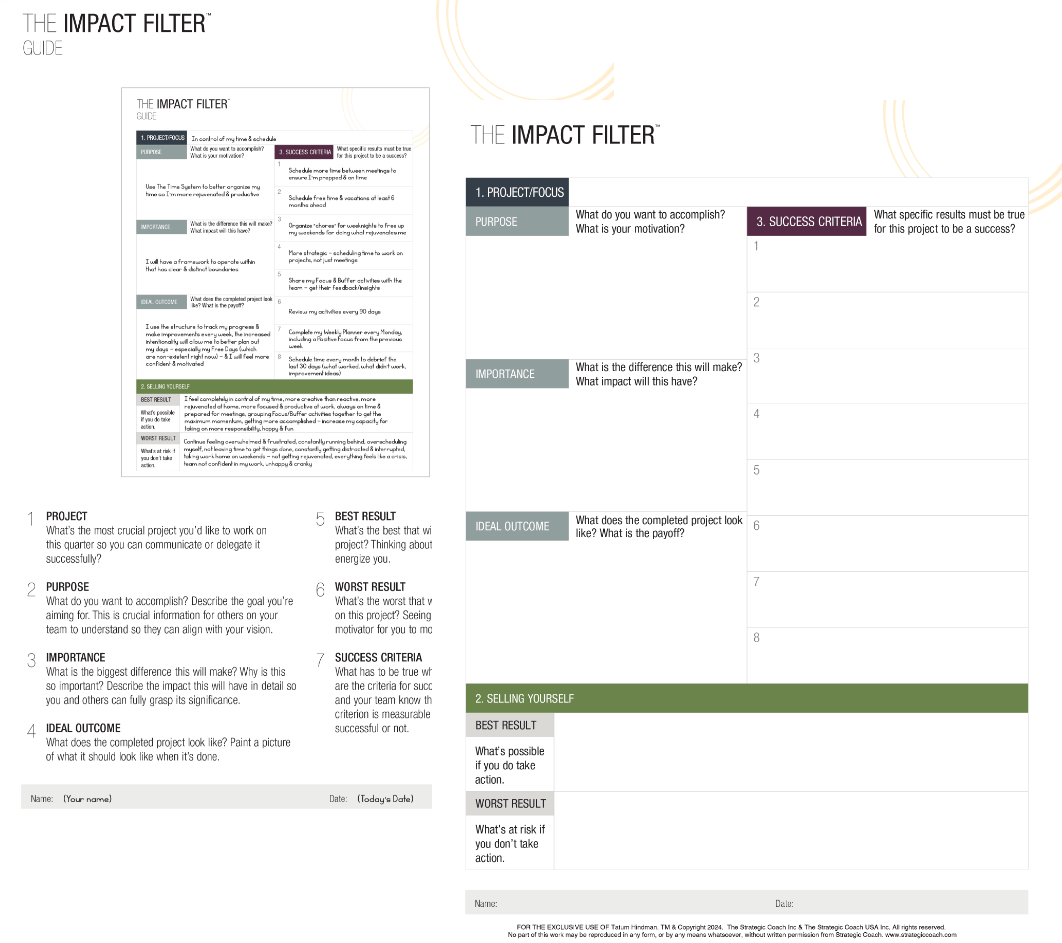

The Impact Filter

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter™ is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.