Why Everything Is Created Backward

July 16, 2024

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey and Dan discuss Dan’s latest book and explore how technological advancements like AI are often perceived as revolutionary, yet are actually extensions of historical innovations. This episode challenges conventional wisdom about creativity and offers a fresh perspective on how we can harness our past experiences to fuel future success.

In This Episode:

- Although we perceive every new technological advancement, like AI, as a game changer, innovations are merely continuations of humanity's long history of tool making, dating back to the first caveman who used a rock as a weapon.

- The term “artificial intelligence” suggests something that is both man-made and potentially phony, but what does intelligence actually mean, and how does AI fit into that definition?

- The language we use to describe our creative process can significantly impact how we approach and execute our ideas.

- Viewing creativity as "putting stuff together in a new way" (as Steve Jobs described it) encourages us to find novel connections between existing concepts.

- Some of the most creative people in the world drew from past experiences and knowledge to create something new.

- Confidence in creative pursuits often comes from within rather than requiring external validation. This internal assurance allows us to tackle new challenges without being paralyzed by potential failure.

- Diverse experiences, even seemingly unrelated ones like parenting and filmmaking, can inform and enrich our creative work in unexpected ways.

- Embracing a mindset of continual learning, rather than focusing solely on winning or losing, can lead to greater creative growth and resilience.

- To put this all into practice, Dan introduces his new thinking tool, The Triple Play™, which connects three seemingly unrelated experiences, leading to new insights and creative breakthroughs.

Resources:

Personality: The Lloyd Price Musical

Learn more about Jeffrey Madoff

Dan Sullivan and Strategic Coach®

Everything Is Created Backward by Dan Sullivan

The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language by Steven Pinker

Book: Connections by James Burke

Episode Transcript

Jeffrey Madoff: This is Jeffrey Madoff, and welcome to our podcast called Anything and Everything with my partner, Dan Sullivan.

Dan Sullivan: Hi everybody, it's Dan Sullivan, and I'm here with my discussion partner, Jeff Madoff, and this is the next episode of Anything and Everything, which we're very disciplined about sticking to the main topic of anything and everything. It gives us a lot of freedom, and yet we have a focus on anything and everything. Jeff, I just sent you sort of an outline of a quarterly book that we're writing at Strategic Coach, and it's called Everything Is Created Backward, and you liked it, which always pleases me.

Jeffrey Madoff: I did. I thought it was a great way to look at things.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, so the reason I hit on this topic is because I'm very connected to the technological world, not directly myself, but through people I know in the technological world. And they're real believers, they're true believers that technology is changing everything and that we can disregard the past because everything in the future is going to be brand new and it's going to be created brand new. And it got me thinking, first of all, just my instinct was that they're true believers. It's a religious term, but people can turn anything into a religion, and I think the future is the way I'm seeing it spoken about is a form of religion. It's sort of a techno-utopian religion. But I'm also a great fan of history, as you are, and I just got a feeling there's always been the newest thing that's going to change everything, probably when the first caveman came up with a rock that was better at throwing than the opposition. I think humans instinctively come up with new tools to multiply their capabilities. And I don't see this newest thing, which happens to be artificial intelligence, is all that much different from what's been going on right from the beginning.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, it's interesting, you know, when you mentioned something to throw the rock better, I actually looked at the rock as an extension of the fist. So how could I disable the enemy before they got close enough for me to punch them?

Dan Sullivan: Because I'm without disabling my fist.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right. So throwing a rock was like throwing a fist, if you will. As a matter of fact, you know, it's interesting because they call it throwing a punch. So I think that it is really interesting because it's always the new, new thing. And the new, new thing prior to AI were smartphones. And then other than, you know, I think the public is finally tired of, do I really need to buy a new phone every 18 months? You know, which is basically a computer I'm carrying around that can also make phone calls. Do I really need to be spending that much money that often? And as that business kind of flattened somewhat, or at least was no longer that exciting, what can you do? And the big question was, what was gonna happen next? And percolating in the background was AI. But one of the first questions that I have, Dan, is why is it called artificial intelligence? What do we mean by intelligence in this?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, it was interesting that they hit on that name because when you look at the dictionary, artificial, one of the meanings is that it's man-made. That's a description, it's man-made. And then it's got a series of other meanings. And my team, one year, bought me the complete set of the Oxford English Dictionary, which is 20 volumes, big, big volumes. And I looked up artificial in the Oxford dictionary, and one of the prime meanings was phony. No, and it's fairly close to the top, phony, that artificial means phony. I said, well, I don't think a new invention disables a previous word. So there's a lot that's really phony about it, especially the proponents who want you to buy or invest and everything. I find there's a lot phony about it. And it was funny because I was just viewing on Zoom a recent conference person who was the maître d' of the conference had five artificial avatars. In some cases, they were an actual robot. In other cases, they were a Zoom robot. And one of the things I found really strange about them, they sort of talked about how intelligent they were. And I said, yeah, but this is California, and they all speak with British accents. Why did your proponent of mechanical intelligence, why do they speak with a British accent? Because I noticed the World War II films, if it was Americans against the Germans, the Nazis all spoke with British accents too, you know. You'll remember the Battle of the Bulge with Robert Shaw. You'll remember the Battle of the Bulge with Robert Shaw was the Panzer Division. And he was a marvelous Nazi, but Robert Shaw is a Brit. But the big thing is, I think that they're trying to fool you with something. When I see that there's a fooling going on, we know it's man-made, that's pretty clear. But the other thing is that it's also artificial, so that means it's not real intelligence.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. Well, and by the way, you just reminded me that Siri, had a British accent, initially. I think we still, in the United States, somehow feel like that accent, at least.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, we had a British client and coach and he had just marvelous, marvelous, I mean, real London based, you know, sort of, they don't call it proper English, but it means basically that you were educated in the right schools and probably you live in London. I said, you know, I wanna tell you something about the people in the room with you. They would pay you to read the telephone book.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, there's something very pleasing to the ears of a British accent to Americans, and there's something very displeasing to British ears about an American accent. It's quite interesting. And of course, My Fair Lady is all based on that premise. So when we get to the artificial intelligence part, the artificial—phony is one possible interpretation of it. But also, the more interesting part to me is the intelligence part. What is intelligence?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I approach it a little bit differently than what is intelligence, because I'm giving, as far as people are concerned, I'm giving intelligence as a given, that we have the ability to be intelligent. And one meaning of intelligent is that what you're saying is understandable to another person. It's intelligible, so there's that meaning of it. But one of the things for me, and I'm biased towards this because it's my living, and you're also biased towards this because it's your living, is creativity is an indication of intelligence. I'm using a Steve Jobs quote here that they asked him what is creativity, and he says it's putting stuff together in a new way. That's pretty broad. That's pretty broad. And they asked him, well, what's really creative? And he says, it's putting lots of things together in a completely new way. But there is a certain basic, almost axiomatic quality to what he's saying. And that is that people who are creative take things that other people see as obvious and they put them together in a non-obvious way.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. Yeah. I mean, one of my favorite musicians is Frank Zappa. And Zappa's definition of music was any sound I can control. I love that. And I think that it's, can you control ideas? And, you know, you talk about intelligence also being a form of communication. It's also interesting because intelligence is also synonymous with spying and intelligence gathering, you know, that sort of a thing. And in a way, since the advent of social media, we as citizens have been spied on. We volunteered. That's right. Under the misguided concept that we were getting all these wonderful social media things for free, when in fact we as the audience were being sold to advertisers.

Dan Sullivan: And we never worked so hard without getting paid.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. So I do think that it's interesting to go to the root words of a lot of this stuff and just figure out, oh, so that's interesting. It's in the same realm as spying, appropriating information, which has now become a huge topic because of AI. That was part of the writer's strike and actor's strike in Hollywood.

Dan Sullivan: Well, and it's part of the rebellion against TikTok that the Chinese are spying. Right.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. So when we talk about intelligence in terms of A.I., I mean, it seems like the iterations on various A.I. software, if that's the right term to call it, software or the A.I. applications, let's say, new ones are coming out daily and the old ones are iterating several times a day. So the machine learning is that it's constantly just taking in information. But does the ability to harvest incredible amounts of information and then be able to retrieve that information quickly. Because, you know, machines can do that much better than we can. Machines can both store and retrieve information way faster than the human brain can. That doesn't necessarily mean intelligence. And before we went online, you and I were talking about Gutenberg, you know, aggregating things because print became more widely used, in a way, was one of the earliest forms of AI.

Dan Sullivan: I read a very good article recently, going further back than Gutenberg, that the alphabet as a form, where you just have a discrete number of letters and then you rearrange them, was a tremendous breakthrough. If you compare the English language, which is based on 26 symbols, with the Chinese language, which a really literate Chinese knows five to ten thousand little ideograms, okay. It takes years. It takes 20, 30 years to become completely and totally literate, where a really willing and capable six-year-old can become very, very literate within a year. I remember I hated school. I grew up on a farm, and I had complete freedom on the farm, and then one day in September of 1950, they took me to a building, took me to a room, stuck me on a desk, and I was supposed to spend time there. Couldn't wander around, couldn't see what the neighbor's cows were doing. It was a very, very limiting experience. And I told my mother, I don't want to go to school anymore. And she said, well, I tell you why you're going to school. You're learning how to read. And when you learn how to read, you can go anywhere you want with your brain. And I said, okay, got it. And she says, and you have to go to school. So we compromised. But I remember just mastering the alphabet. Well, the alphabet, you know, as far as we can tell, came into the Middle East around 800 before the Common Era. So it's 2,800 years old. And the people who took to it faster than anyone else were the Greeks. So if you think about the foundations of what we call Western thought, it's Greek, because they were the first ones to master the alphabet almost as a culture. You know, they had papyrus in those days, that had been invented a long time ago, so they started turning out books or scrolls and everything like that. But I can put the alphabet up against any modern invention as being more revolutionary. And then printing, you know, widespread printing. Printing existed before Gutenberg, but they didn't have movable type. So, you know, the alphabet is movable symbols and printing is movable type. then you move into the digital age, and now you're moving digital representations of type and numbers. The other one is the Arabic numbering system with zero. I mean, there's a case to be made that the Romans collapsed because they had a really bad way of counting. How much gold do we have? I'll tell you in six months.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, it's interesting where everything else is clear, one, two, three, up, so on. Zero is an interesting concept because it means nothing, right?

Dan Sullivan: Or it means ten times.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, or it just means that's the breakeven point between something and going into negative numbers. But there are cultures that had no alphabet. And there were African cultures that communicated through drums sounds, percussive sounds, that were considered to be way more expressive than alphabetical sounds. I read The Language Instinct by Steven Pinker, which was really fascinating, you know, getting into the origins of language and that not all languages are alphabet based, you know, which is quite interesting. But in a way, that ties in very much the way it ties into what your thesis was about looking backwards in terms of invention. So talk to us a little bit about that.

Dan Sullivan: The title of the book, and these are small books, so I create a small book every quarter, and this is book number 38. And as I said, everything is created backward. And what I mean is that the most creative people actually go backward to things that have already happened, and through a process that I think is mysterious, put things together. And my sense about that is three seems to be the magic number of things to be put together. And I've actually created a thinking tool which the book goes on to explain this thinking tool, which is called The Triple Play. And what you do is you take three experiences, and I start with the individual. I don't start with something that's going to be a product necessarily that you produce for other people, but it's a way of being creative with your own experience. And what you do is, for example, I give later on in the book, I give five examples. of how The Triple Play will work with your experiences. And the first example is things that you're still unhappy about. And what I say is that it's something that happened. It could have been last year or it could have been five decades ago, that when you think about it, you still get a negative cringe from it. And I say, now, if I get you to write those in our tool, we have three arrows, and you write the first unhappy thing, the second unhappy thing, the third unhappy thing, and then around them I put three boxes. they're sort of in a circle. The arrows are in a circle and the boxes are in a circle. I said, now what I'd like you to do is to pick one of the boxes and link it to two arrows that are closest to it, and then write down what the unhappy experience is in one box and the unhappy experience, so two unhappy experiences, and then make a connection between the two unhappy experiences in the box, okay? But that's just one of the boxes. Then you go with another box, and it does two, one of which happens to be one you've already used before. So it's A and B, and then it's B and C, and then it's C and A. So you go around in the circle. And what happens is that the moment you complete the three boxes, connecting two arrows, connecting two arrows, connecting two arrows, you're not unhappy at all with those three experiences. And the reason is you change the context of the experience.

Jeffrey Madoff: So can you give me a functioning example of that?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I'll give an example, particularly unhappy dating experience I had when I was a teenager. Okay. And then another one was, I'll keep it in the same vein, my divorce to my practice wife. I call it my practice wife. I didn't used to call it my practice wife. And then another one is a business partnership that fell apart. And I still, when I think of the three things, I still think of it, yeah, but that sucked. But when I put the three of them together, I came to an understanding that in all three things, I didn't really tell myself before I got involved in those relationships what I was looking for. And because I didn't get what I was looking for, that felt like a failure, and it felt like an experience. But I can say, anytime you don't tell yourself why you're getting involved in something, it's probably gonna be an unhappy experience. So that would not be just all three experiences. That would be all the unhappy experiences in my life. I was disappointed, but I was disappointed because I never had my mind clear in the first place what I was trying to do.

Jeffrey Madoff: So what's a question one can ask themselves to avoid that?

Dan Sullivan: Why are you doing this? No, it's a good question. I mean, you've obviously been through this over the last five or six years with your soon-to-be Broadway play, and you're asking yourself, well, why am I doing this anyway? How old were you when you actually started Personality as a project?

Jeffrey Madoff: 67, 68, something like that.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and now you're older. I've aged during our conversation. Yeah, but what was the prime thing? Because, I mean, it's one thing to commit yourself to this in your mind, but when you announce it to other people, then it becomes something much bigger, okay? And the other thing was, it was about a particular person, Lloyd Price, who was alive and who you really respected. You wanted to turn his life, at least his being a music pioneer and music revolutionary, if you will, you said, you know, this needs to be a play, you know, and you were in New York. So where do you have plays in New York? You have them on Broadway. So why did you want to do that?

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, first of all, I'm seduced by ideas. And that's what attracts me to things. So probably to my financial detriment, the attraction isn't, oh, how am I gonna make money doing this? That comes later, because that becomes a practical concern, because if I wanna spend a lot of my time doing a play, I better figure out how I can make money doing a play. Same thing with my production business, same thing with teaching, all these things that I enjoy doing, a common thread is, they all involve storytelling. And none of the motivation was financial success. That to me is a byproduct.

Dan Sullivan: But financial success is necessary for the story to be told.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right.

Dan Sullivan: And to get it out there. Okay, I'm just going to stop you there. What are two other things you've done in your life that match this one in terms that you got seduced by an idea?

Jeffrey Madoff: Getting into filmmaking. Okay. And, you know, doing that for as long as I did, like over 40 years. And then the third one? Becoming a husband and father. Okay. That's a huge life-changing thing. Okay.

Dan Sullivan: So... You just lessened your future options.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, now my kids are old enough, they're back to being increased. They've been invested in my play.

Dan Sullivan: The big thing about parenting is the speed with which you can turn a liability into an asset.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes. Yeah.

Dan Sullivan: I'm just going to do it. Let's take, they don't seem connected, but I'm going to have you connect them. So I'm going to take the Personality play and I'm going to take deciding to get married and be a father. Okay. So what's the connection between those two things? Well, the common thread is me.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, that's good. That's good. I'm involved in all of those. Yeah. And, you know, it's interesting in the looking back, even stuff from my relationship, you know, and difficulties that I've had and successes I've had enabled me to identify with, you know, the ups and downs of Lloyd's life, which I think resonates with other people and the ups and downs that they have had. And when I say that money was never the primary mover, and it's certainly not that I was independently wealthy, but I always felt that I was always been able to figure out how to make money doing what I'm doing that I love doing. There's lots of ways you can make money that you hate. But I wasn't ever willing to do that. And, you know, that's why I even named my course that I taught at Parsons for 16 years, Parsons School for Design, Creative Careers, Making a Living With Your Ideas. And I think, you know, one of the things that you're talking about, then correct me if I'm wrong is, you know, so why are you doing it? And I think that things that really engage you, give you a sense of purpose. You have that with Coach and you're past the point where you're worried about the income from it, but the constant tools that you're creating, the new people that you meet, all the things that you and I share, tremendous curiosity about anything and everything, which I hear is a great podcast that people should listen to, and I think that it's that purpose and the desire to share experience and ideas and learning, and from all the things that I've mentioned to you, be it doing the play, my production company, teaching on a college level or any level, but I have some Z college, also being a husband and a parent. There are things that I have learned through all of those things, the difficulties and the successes have all informed each other. I think if your eyes are open, everything you do informs what you do. Yeah.

Dan Sullivan: OK, so we did the parenting and we did the Personality play. Let's try out parenting with the beginning of your film career and see if you can see a connection there that's different from the first one that you made. Something new that you see by doing those two, you know, connecting those two, that's different from connecting the first one.

Jeffrey Madoff: I think that the link is the experience gained that if you are emotionally open, can lead you to deeper and more relatable insights, whether you're telling a story about Lloyd's life, whether I'm making a film or not.

Dan Sullivan: But you did a documentary film first.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right.

Dan Sullivan: That's where you found out about the life.

Jeffrey Madoff: Exactly. That's right. Yeah. And you know, I did the same thing with Ralph Lauren. Yeah.

Dan Sullivan: So you did one with Shirley Horne, too, didn't you? I did.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. I've done a number of them.

Dan Sullivan: How many would you say documentary where it's about a person's life, about their career?

Jeffrey Madoff: Martha Graham, who created the art form of modern dance. Brooke Astor, who is a cornerstone of New York philanthropy and just an amazing, amazing woman. Shirley Horne, Abby Lincoln, who is also a great jazz singer like Shirley Horne. Liza Minnelli, Renee Fleming, the great opera singer. I mean, there's been a whole lot of people that I have done that with. And so that learning how to tell a compelling story and realizing that everybody has their stories and there's lots of experiences that are common to all of us. And when you can create that resonance, you know, one of the reasons it's interesting, you know, one of the reasons that I wanted to do a play instead of a film is the immediate emotional impact that a play has, because it's live and you're at risk and things can go wrong every night.

Dan Sullivan: That's right. That's right. Sometimes in the afternoon, yes, they go wrong in the matinee.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. All of those things. And it gave me an also a certain perspective. And there's a bunch of things that have, I think, that have impacted me, that have given me perspective on things. You know, at our age, we've all experienced loss. You know, we've experienced things that, if you look at those things, and I mean really look at those things, I think it can create a greater sense of both compassion, but also allows or facilitates the telling of more meaningful stories. I certainly have no desire to set up an armored picture that no one can penetrate in terms of these stories I'm telling. And what Lloyd said that was so great when we started off on this journey, because I said, you know, you're not going to look good in all this stuff. There's stuff that you did in your life. And he said, Jeff, the truth needs no defense. And I thought that was just, you know, fantastic.

Dan Sullivan: That's true in marriage and parenting, too. That's right.

Jeffrey Madoff: It is.

Dan Sullivan: It truly is. All the problems come from not telling the truth.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, that's right. And as we've talked about before, then you have to remember which lie you told them. I mean, I do see hand in glove so many things in life which have to do with one's career, one's job, one's relationships, all of those things. And I think purpose, and I'm not even talking about it in the... Well, it's certainly meaning.

Dan Sullivan: It's certainly meaning. Yeah. I think purpose and meaning go together. We create our meaning with our purpose. But at the same time, we create our purpose with our meaning.

Jeffrey Madoff: And because whether it's birthing children or birthing an idea, you know, you have no idea what the outcome is going to be. So life, as you say, is guesses and bets. You don't know which you can either look at that with trepidation and fear or embrace the adventure that it is. And I'm not saying that in any kind of Pollyanna way. And I think that that's really important. As you have spoken about often, your divorce was the end of one thing, but it also facilitated a new beginning in something else.

Dan Sullivan: Same thing with bankruptcy. Two bad report cards that I took seriously.

Jeffrey Madoff: Which is smart because look at what the outcome has been. And I think that with you, and I like to think the same of myself, what you see is what you get. There's not a facade going on. Is there some self-protection? Of course there is. But we have met many people that are just a projection of what their desires are as opposed to what the reality is.

Dan Sullivan: So, the thing I'd like to point out that this has really been very, very eloquent, it's been very multi-dimensional, and it just came from you putting three things together. And that's The Triple Play. And what I'm saying is, I think this is how all creativity happens. When it happens, there are three things that are personal to the creator that they just put together and drew new meaning. I mean, what have you learned just from identifying and talking through the connections among these three things?

Jeffrey Madoff: What I get from it is, frankly, reinforcing, because one of my mantras is, everything you do informs everything else you do. So I have always looked at what I'm doing as, you know, where did this come from? You know, what is this about? And as I said, even why, as a filmmaker, I decided to do a play. You know, so that's an examination that has always been kind of a part of me. I've never been just, well, we'll see what happens. You know, that's not how I've ever operated. And because I try to know as best as I can, and we're all flawed in this, why did I make that decision? You know, what is it? And I think we construct our own narratives to help our lives make sense, and those narratives change as we change.

Dan Sullivan: I believe that's totally true. Okay, so as I started this section out, the thesis of the book is that all creativity comes from turning around and looking at things that already exist. And part of the reason for that, you're creating with things that are actually existing. I mean, the three things that exist, they had enough survivability that they could exist, okay? Then what I find really interesting is the fact that the, I call them techno-utopians, now believe that the past doesn't matter. We're just creating things in the future. We're just creating possibilities in the future. And I said, well, do the possibilities exist? And they said, no, it's just a possibility. And then I said, well, I don't think you're working with anything. There's no actual experience. There's no actual emotion. There's no actual existing meaning. There's no existing impact that you're working with. You're just working with possibilities. The British and the British language, they have a term called wanking. I'm not going to say out loud, but it's easily accessible in any dictionary. And it's very funny. We were at a conference and one of the CEOs from a major tech corporation was there. He said, you know, what we're doing is we're taking young people and we're creating the future. We're just taking a lot of young people, putting them together. And we start with about 40 and we get down to a group of around eight. And they are creating something that isn't imagined right now. And they're creating something imaginable. So I went through one example of what he was talking to, and I turned to the people that were at the conference, and I said, when does a customer get involved in this? I mean, ultimately, you want to create something that people buy, I guess. I mean, in your world, my world, there's what you hope people will buy, and then there's people buying, and there's a sharp difference between the two. One of them is a guest, and the other one is a bed. You know, what all of us do is we want to make such great guesses that people will bet on them. With dollars. I prefer American, living in Canada. But what I want to say is that that was a master class that you gave. I bet if you were in a setting and you just went through these three experiences, I want to tell you how I see three experiences from my life. My creation of a soon-to-be Broadway play called Personality, The Life of Floyd Price, and then my decision to be a husband and a parent, and my decision earlier, many years ago, many decades ago, to actually go into a film career, I'm going to put all those three, you would have an absolutely rapt audience, R-A-P-T, rapt audience for as long as you were talking. I'm just saying, you just created a master class out of that.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, you created the framework of that. From our conversations, both in the podcast and sometimes the boundaries between what we've said before and after, like 20 minutes that we're talking beforehand or half an hour and say, oh, shit, we didn't record that. But I feel like I know some of those formative things in your life. And I think that the earliest skill and talent that you embodied that I think really was significant in setting a direction for your life was the older people you came in contact with when you were a kid and getting them to talk about themselves when they were kids my age.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Yes. Yeah. And when you were my age, what was going on in the world? And not only did you know that that could get you a glass of milk and two cookies, you know, long enough, I get two glasses of a complimentary phone call to my mom. What a smart kid she had.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. But in terms of the dynamic of it, we're Strategic Coach. You're talking to people. in a way that's not unlike what you were doing 75 years ago.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, totally.

Jeffrey Madoff: So it makes sense. And to me what always never made sense is, you know, I mean, you can find the reasons, but what I'm saying is that those things that light you up when you were younger, that you get positive reinforcement for, that you love doing just for the sake of doing, to me, if you can make a living doing those things, you're going to be a much happier person.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and you'll be much more successful, too, because you won't be hopping from one disappointment to another.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, that's right. And so going back to what I was saying at the beginning is that none of these are hobbies. So, you know, my desire to do a play is not a hobby. And when I'm asked, well, is this a labor of love or is this a commercial venture? My answer is yes.

Dan Sullivan: A hobby that got out of control. Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: And the phrase that you have used, which I love and have given you due accreditation whenever I say it by saying my dear friend, Dan Sullivan has a phrase that I love, which is making your future bigger than your past. I love that because imbued in that is a tremendous sense of optimism. And I think that maintaining an optimism in one's life is critical. And it's interesting, one of the great things about teaching, and I was just a pitch coach this past week for these six different companies from Denmark, which was really interesting, but the thing about that is when you have a sense of purpose, when you have a sense of optimism, and optimism, I'm not talking about Pollyanna, But yes, at a time when a lot of people are thinking about retirement, I've undertaken the largest task I've ever undertaken professionally. At a time when most people are thinking about retirement, you have had back-to-back your best years in business ever. I think to be an entrepreneur, you also need to be a bit delusional. And I'm not saying that in a bad way. It's not being afraid to dream and to go for it. But what are you thinking now?

Dan Sullivan: The word delusion is a negative. I'm not sure I entirely agree with it because all three of your experiences that you talked about, the unhappy, well, they weren't the unhappy experiences. We just put three experiences together. But those guesses and bets were based on a huge amount of previous experience. So you weren't making up things with any of the three. I think delusion is, there's no external reality. There was a lot of external reality with Lloyd. It was his entire life. You know, you had a practice marriage first, right?

Jeffrey Madoff: No, no, that was the first.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Yes. I thought maybe you did. Oh, this was it. This was it. Well, you did well on your first crack, you know.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I needed some remedial.

Dan Sullivan: And then your filmmaking, that was based on a lot of reality. And my sense is a lot of what people call creativity now is actually delusional.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, and let me be clarified, I'm using delusional somewhat tongue in cheek. Okay. And what I mean by that is for me, who has never written a play before, to put that together, to put together the team I have, and to actually get it out there in front of paid audiences, you know. And you get great reviews. Yes, and so the initial thought was, what, are you deluding yourself? What makes you think you can do that? But I never ask myself what makes me think I can do it, I just try to do it. So that's what I mean by delusional. And you've said this far too, it's a certain part of entrepreneurship, ignorance is a blessing. You know, because if you knew how stacked the odds are against you, but- You'd be working for the government.

Dan Sullivan: Yes, that's right.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. So the delusional to me is just the awareness that you're tackling something.

Dan Sullivan: You know what, I want to suggest a distinction here. And the distinction is where does your confidence come from? Does it come from the outside or does it come from the inside? I think you have a great deal of self-assurance. Where do I think that comes from? I think it's factory installed. And you had the right conditions. You had parents that were a positive influence and you had everything else. But in my case, I don't have to have any evidence for what I want before I make the decision to get it. I was born confident, you know, I just have a natural confidence. What's the worst? I can learn something that I won't do again. What's the worst that can happen? Failure is not learning. I was saying there's three teams in life. You're on one of three teams. You're either on the winning team, which has its rewards, or you're on the learning team, which has its rewards, and if you're on the losing teams, it means that you're neither winning nor learning. Okay, and I think that people who have low confidence, they don't have the experience of being on the winning team, and they don't have the experience of being on the learning team. All they have is an experience is that everything I tried failed. That's because I'm a failure.

Jeffrey Madoff: Which a lot of people think is also factory installed, so to speak. I definitely believe that the relationship that I had with my parents was hugely formative.

Dan Sullivan: Me too.

Jeffrey Madoff: And that the fact that, you know, they encouraged me doing the things that I like doing because I could draw, and I love drawing and telling stories. They would bring me home big sheets of craft paper from the store so I could draw big pictures. Then you took over the basement. Took over my bedroom, but my bedroom was my room, so I could do what I wanted in it. My parents didn't say, you have to do this or you have to do that. I feel, I don't know what the word is, when I think back of the relationship that I had with my parents and other people I know who unfortunately did not have good relationships with their parents. And, you know, I think as we get older, it becomes more and more obvious who is having to overcome certain difficulties and who plays those out and oftentimes even sabotages themselves and they just can't help it, you know, because of that. You know, but there's also, you know, the two siblings who come from the same parents at the same time and have different experiences of the parents as if they're not even talking about the same people, which is kind of interesting, too. So I think most of our formative things are the same things that were formative things back in ancient Greece. I don't know that people fundamentally have changed. I don't think they have.

Dan Sullivan: And that's the other thing, you know, what got us going on this topic was the topic of artificial intelligence. I said, you know, I find it really handy the same way that I find graphic user interface really happy. You know, if I'd had to learn codes to use my personal computer, I wouldn't be using a personal computer. And I think that artificial intelligence doesn't have meaning, doesn't have purpose. It can only assist you with your meaning and purpose.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. And the problem is, I mean, I think that's in the best of worlds, that's true. And in the real world, the other thing that happens is there will be people that will use it to con and deceive.

Dan Sullivan: Which they did with other means before this.

Jeffrey Madoff: Exactly. Because humans are involved. Yeah, I think it might have been Socrates who said shit happens. And so I think that, you know, that's the case, that there will be things that are corrupted. I think back when television was starting out and there were two phrases. One was television is the window on the world. And the other phrase uttered within weeks, I don't remember which came first, but they were pretty much synced in time, was television is a vast wasteland. Newton Minow. Newton Minow said that. I think that first was, yeah, he was the head of the FCC at that time. And I can't remember if it was Bill Paley. I don't remember who.

Dan Sullivan: It would have been Bill Paley because he was selling television.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right. But I think both of those are true at the same time. Yeah. And as it's true that AI can be, as you described it, in this fantastic dumb assistant, so to speak, that can just retrieve material faster.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, it's a useful assistant. That's right. Yeah, it's just useful. I just find it useful, you know. All the technology that I utilize every day I find useful, you know, and when improvements come, I'm pretty quick to adapt the improvements. But I was saying I have an Oura Ring, you know, which measures your sleep. And I said, I'm really happy I have that Oura Ring because it gives me a reason to keep my cell phone charged up. Cause it only measures as long as you have your cell phone, you know, actually it measures. It just doesn't give you the results unless your cell phone. So my whole point is that I don't feel deprived that I'm not using hundreds of other technologies. I have the technology that I need to move me forward in what I want to do. And that's the only reason technology is important to me.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right, I mean, because why else would it be, right?

Dan Sullivan: But it hasn't changed me from what I was interested in when I was eight years old.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right, same with me. I learned typing when I was a kid. I was the only male in the typing class at Firestone High School, and the first thing the teacher said to me is, why are you taking typing? Well, I have a sister who's four years older than I, and when she went to college, she was typing up people's term papers, and she was a fast typist, and so I don't remember if she was making like $3 a page or whatever, but she could make an extra $30 in not much time, and that would finance a fun weekend, or whatever she wanted to do.

Dan Sullivan: She could buy something. You were talking about the six days, too. Yes. She must be my age.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right, so I saw that she did, and I said, well, this is useful. This is a useful skill. And what I had no idea was just how useful. Yes, it was useful in college and I typed my papers and I wrote my first book and all that kind of thing. And I remember my aspiration was, I want to get one of those IBM ball typewriters.

Dan Sullivan: That's really cool. Especially when the IBM Selectric came out. And you could reverse your mistakes on the tape and then it would type out the... That's right. That was marvelous.

Jeffrey Madoff: It was great. It was great. And how clever it was that ball that went around because you didn't need the different keys. Yeah. So, I mean, that was terrific. So I thought that would be a really useful skill to have because I could make money. And, of course, type my own papers, not have to pay anybody to do it. But the other thing is that I didn't anticipate what was a huge, huge bonus was personal computers weren't alien to me because I already knew how to do the input device, the keyboard. So my adaptability was really quick. And what I did, there was a company called Eagle Computer. They were one of the first PC clones. And there was this guy who sold Eagle Computers, and it was a kit. You could buy them finished. And I said, I'd like to build one. And he said, you would. I said, Yeah, he said, well, we can do that. We can do that. And so I remember when I started it. And this was, you know, I mean, literally from the motherboard up, I built the thing. And it booted. And I thought, oh, this is really cool, and I never have to do this again. But doing that gave me a certain satisfaction. I had some sense of actually how it worked and what to do. And who knew that that payoff of learning how to type back in high school 30 years later would facilitate, or 20 years later, facilitate me inputting in a personal computer.

Dan Sullivan: Really interesting, my typing skills are a result of the Vietnam War, because right at the beginning, April, you know, the Gulf of Tonkin, that was the excuse that Johnson gave for starting the war. Well, the war had already started, but it became official. They started drafting from 25 downward. and I got sent to Fort Knox, where they took a whole bunch of aptitude tests, and they said, certain people are gonna be out fighting, and you're gonna be back in an office, so we're sending you to typing school. We want you to know how to type. And I did that at Fort Dix, not too far from New York City. And I always think, I was so happy, thankful for the army, that they taught me how to type. Because my whole career has been based on, you know, do-do-do-do.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and how that enabled you to put your ideas on paper and communicate them even in early stages.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, it's fantastic. I've never learned how to use my thumbs.

Jeffrey Madoff: No, me either. My kids on their phone.

Dan Sullivan: I'm a klutz. I'm a klutz. Anyway, Jeff, where would you stand now on just exploring the idea that everything is created backward?

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I believe that that's true. You know, you and I have talked about this program that was transformative for me, and I think you liked a lot too, called Connections. It's by James Burke. He is a science historian, British. And you can find this online, I think even for free. I think YouTube's got season one of it, which is the only season you need to really watch. It's brilliant. But it changed my thinking in terms of looking at the antecedents, what came before. Because I think if you're missing context, you can't possibly understand, no matter what it is, whether it's AI or whatever it is, you can't understand these things until you look at those antecedents, the things that led to that—the internet, the cell phone, and satellites allowed GPS, which gave birth to Uber and Lyft, right? So there's all of these things, you know, that look backwards that you're saying, and the things that came together. I think that if one understands that, it opens up a pretty big world of possibility of other things that you might combine that could be really interesting and fruitful. So I think that you created, when I was reading that before we got online, I just thought, yeah, this is really interesting, and I'm very much in sync with that approach. It's really good. I don't understand why people aren't more curious, because that's the only way you learn.

Dan Sullivan: I would suggest two reasons. They think they're not creative, number one. And number two is they basically think that there are special other people that create things. So why should they be curious? Because they're never going to be in charge. They're never going to be in control. You know, they're never going to be seen as important.

Jeffrey Madoff: And here we are now hearkening back to another piece of theater you just remind me of. The phrase is attention must be paid. And that's from Death of a Salesman, Willie Loman, a great archetype, you know, in American theater and literature, who felt that way, that you're saying, so where does that come from?

Dan Sullivan: I don't know. I think how one gets off to a certain life is pretty mysterious. You can have identical twins who are genetically identical, who are more or less born in the same conditions, experience the same experience. Oftentimes they dress alike and turn out totally different. How does that happen? Then they find the question which one was born first can have a big impact. One's born four minutes before the other. That makes a big difference. They found out that one of them was more dominant inside the mother, and that becomes a big difference. My sense is it's totally unpredictable what humans will pay attention to. Mm-hmm.

Jeffrey Madoff: I think that's right. And because they're paying attention to X now doesn't mean they'll be paying attention to that later. I think that's true.

Dan Sullivan: Divorce is proof of that.

Jeffrey Madoff: There's a fantastic series on Turner Classic Movies. It's a six part documentary called The Power of Film.

Dan Sullivan: I downloaded it. I haven't started it yet. Oh, did you?

Jeffrey Madoff: It's great, because the question that he poses, he said, I'm not interested in what films were successful. What this is an examination of is what makes films memorable. And because there are many films that were highly successful that disappeared. Yeah, nobody cares.

Dan Sullivan: Well, and the classic memorable film is The Wizard of Oz. Mm hmm. It didn't do well. Right. And the other one, Citizen Kane, because Randolph Hearst controlled the media. Right. And it was what he considered to be a negative depiction of him. That's right. These are in the top 10. These are in the top 10 all time movies. That's right. Casablanca wasn't a real knockout when it came out. That's right.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. I think, though, it's a really interesting point of view, not just in popular culture like film, but what is it that makes an experience memorable? You know, because there are things that get your attention. You know, I did this thing in my class a few years ago. You know, there's like 60 students in there. Everybody's talking and all that. And I walk in and they're all just talking. And I took one of the molded plastic chairs and threw it across the room. And that makes a lot of noise when those things hit the asphalt. Students are reacting, all that. And I said, okay, what did I just do, aside from throw a chair across the room? And there was silence. I said, come on, think about our last class, what we did before. What did I just do? And the previous class was about advertising and marketing. Then I see somebody go, you got our attention. I said, say that so everybody can hear it. I said, you got our attention. I said, that's right. Now, I did a cheap trick to get your attention, but now what do I have to do if I wanna build a relationship, maybe get you to buy something or get your attention to hear my pitch? And I said, follow it up. I said, that's right. And following it up means what? Keeping our attention. I said, that's right. So getting your attention and keeping your attention is essential in business.

Dan Sullivan: From a linguistic standpoint, from a language standpoint, the easiest way to get people's attention is to ask an open-ended question. In other words, they have the answer to it, but you don't have the answer to it. Yeah, I mean, virtually our entire podcast series has been based on that. I mean, you don't ask me questions and I don't ask you questions because we have an answer you want to guess at. What do I win? Am I close? Well, not quite. No, I can't stand rhetorical questions, you know, where people have an area of knowledge and then you have to guess the knowledge or show that you memorized what they told you. I find that totally manipulative.

Jeffrey Madoff: I had two things that reminds me that happened when I was in college, and I had a double major in philosophy and psychology. And my second semester freshman year, I took a course in basic epistemology, which is theory of knowledge. How do you know something? So we were on the sixth floor of Bascom Hall, and the professor walks over to the windows and says, you may see this as the window, but I see it as the door. And they said, over there, you may see that as a door, but I see that as a window. He said, who can prove me wrong? And I raised my hand, and I said, first of all, what is this course? And he said, it's basic epistemology. And I said, how do you know? He unfortunately didn't have your response. He's just wondering, who's this wise ass I'm gonna have to put up with for an entire semester. And then I walked over to the door and said, criteria for belief is the confidence to act on what your belief is. So I'm going to leave this classroom through what I see as the door, and I'd like you to leave through what you see as the door, and let's see how much you believe what you're saying and how you know what you're saying.

Dan Sullivan: Well, you know what I would have done?

Jeffrey Madoff: Kicked me out of the class?

Dan Sullivan: No, I would have given you an A and kicked you out of the class. One, you're not pissed off. Well, it would prove one thing. I had a client I went to dinner with this week. He lives in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, that little stretch of land between Massachusetts and Maine. And he went to graduate school, he got his MBA, and I think he went, might have been one of the Ivys, I don't really remember. But there was this M&A company in Portsmouth, and the guy approached him. This was 1980, and if you had an MBA, you could name your price. It was a real hiring period at that time, you know, master of business administration. So it was like a job fair. He came up to him and he says, can I ask you a question? He says, what's the least amount of money you can live on for a month? He says, what's the least amount of money? And my client, Pete, says, what do you mean the least amount? I'm looking for the most amount I can get on a month. And he said, I know that, but what's the least amount you can get? He said, no, no, I've got an MBA, the big banks want me, everybody wants me. He said, I know, but what's the least amount of money? And it took him five times. And he thought through, and this is 1980, so he says, $1,200. He says, okay, so he says, I'll tell you what, I'll give you $1,200 a month, but you get a third of everything you sell. And Pete came back and said, is there a cap on that? And he said, no cap. And he did it, and now he owns the company and everything. But in that moment, he proved that he was an entrepreneur.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right, yeah. Well, once again, we've been true to our title, Anything and Everything. And Dan, I think we stayed within the boundaries of anything and everything. So mission accomplished.

Dan Sullivan: I feel confident that we can't go outside the boundaries of anything and everything. I'm developing that much belief and confidence in what we're doing.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, yes, my confidence has become a capability at this point. I agree with you. So looking forward to the next one. Thanks for joining us today on our show, Anything and Everything. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend. For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

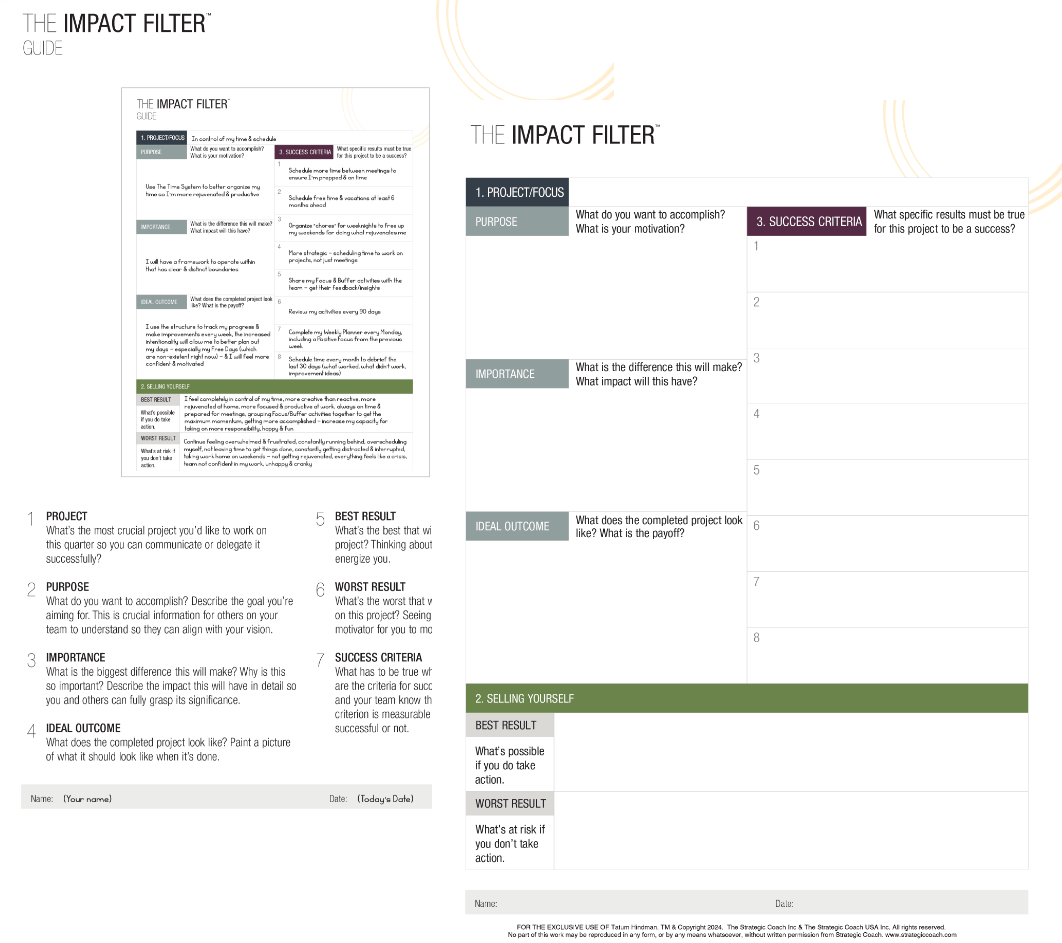

The Impact Filter

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter™ is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.