Protecting Your Humanity In A Digital World

October 23, 2024

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

About 50 years ago, the microchip had people making predictions about how the technology would influence all areas of human life. Now, advancements in artificial intelligence are generating the same sorts of predictions. Dan and Jeffrey discuss the psychological effect of AI’s potential, the very different mindsets with which people are approaching it, and who is set to benefit the most.

Show Notes:

New technologies can force people to rethink their relationship to work and to everything else in their lives.

If you want to remain human, you have to adopt a theater-based attitude because the attitudes related to computers take the human out of the picture.

Every technological advancement has given a certain advantage to early adopters.

When it comes to technology, the playing field levels rapidly.

There are people whose mentality is that machines are good and humans are bad.

There's a certain Ponzi scheme quality to the way early investments are done.

In some industries, money isn’t made in coming up with new ideas, but in taking advantage of other people being enthralled by new ideas.

There are businesspeople who have been almost deified by a certain level of consumers.

The new luxury and desirability come from something that has the human touch.

You can get so far into the world of new that you've lost touch with everything that already exists.

Every time we lose the ability to connect and share an experience with others, we’re losing something fundamental to what we are as humans.

Theater is the ultimate in a shared emotional experience because it's live.

Creating a brand can be all about storytelling, theater, and connection.

Resources:

Casting Not Hiring by Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff

The Gap And The Gain by Dan Sullivan and Dr. Benjamin Hardy

Learn more about Jeffrey Madoff

Dan Sullivan and Strategic Coach®

Episode Transcript

Jeffery Madoff: This is Jeffrey Madoff, and welcome to our podcast called Anything And Everything with my partner, Dan Sullivan.

Jeffery Madoff: We don't like limiting ourselves and figure we have a big playground. And our playground today, we're going to talk about who you play with, which is other people. And we're going to talk about how AI—which everybody is talking about, everybody is curating different kind of apps and everything else—where it's having an impact, where it's not, and how important the human connection is, which is something that I think a lot of people are overlooking. And I'm going to open us up with talking about the invention of computers because we were going to have so much extra time when computers became a part of the office. And in the early '70s, you could actually get a degree in leisure studies, a new area that was going to help people deal with all the extra time they'd have, which of course never happened. And I think that we're at a real crossroads now. And just before we started recording, which prompted us to get into recording without us usually talking for an hour and a half before, Dan, you were talking about a kind of inflection point we're at with computers, AI, and people. And I'd like to build on that. So if you would bring us up on that.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I got very interested in computers in 1973, 1974. And because it was the first time that the term "microchip" was being used and all sorts of predictions were being made about the impact of microchip-enabled technologies and the impact they would have on organizations and on individual creativity. And that's right at the time, so this is 50 years ago actually, that really has been a foundational thought in the development of Strategic Coach, which is the company that Babs Smith and I have created. And what crossed me, because I'm much like you in terms of our college education, I was what could be described as a philosophy and psychology major in college, which we share that. And it really, really struck me that the impact of this microchip revolution going forward was really going to be psychological and emotional, and that humans were going to have to rethink obviously their relationship to work, but they were going to have to rethink their relationships with everything else in their lives because of the steady impact of technology where everywhere they went, this technology was going to be playing a part in how they lived their lives.

So I'm in cottage country today, but we have really good internet. So if it was 50 years ago in cottage country, you know, there wasn't technology. And I wouldn't feel good if I had to go through a week at the cottage without the internet, because I like the internet. And besides, you'd be disappointed because we missed our podcast call while I was at the cottage.

Jeffery Madoff: I would be.

Dan Sullivan: So one of the things, it was just because you and I have been talking about theater lately. You and I have been writing a book, which is going to press in a matter of a week or so called Casting Not Hiring, the difference of thinking about entrepreneurism and how you create an entrepreneurial team using a standard term called hiring, which is like corporations do, or using the word and the activity of casting, which is what theater does. And it began to occur to me before we came on today that there's a binary choice that's being made in society now, that if you want to remain human, you have to more and more adapt the attitude of theater because the attitudes related to computers take the human out of the picture. So that's what triggered our thoughts about what we would do today.

Jeffery Madoff: And it's interesting because when you think back, going back to the 1950s and the UNIVAC computer, and of course IBM's computers—and IBM, by the way, over the next 70 years, they started Watson, which was the exploration of the different kind of intelligence, AI being part of that. And what's interesting is that they would pit computers against a chess master and somehow would reach the conclusion that once it was able to beat that master, that it was smarter. So I think, you know, you need a definition for what is smarter or what does intelligence actually mean. But it's interesting because it's always comparing the human to the computer and how the computer is going to win out, you know. And, you know, the science fiction books even going back before that, you know, was the fear of robots taking over and that kind of thing. And I think that we're now entering this new reality with the promise and threat of AI. And what are the essential differences that we will experience?

And you and I both know people, and I get emails all the time from others or see things on LinkedIn or whatever about people who are telling you the next hot tool that you've got to learn that's going to save you X amount of time a week and that you don't have to do all this boring stuff you had to do, that it's all going to be done by AI. And it struck me, there's something really interesting about this. And what's interesting to me about it is that every technological advance has given a certain advantage to first adapters. Of course, some things never pan out. But that first advantage, that first mover advantage that you have, but then if it's actually something that takes hold, eventually everybody had computers on their desk. Everybody had mobile phones. Everybody had electric typewriters. So the advantage that you got wasn't an advantage for very long. And it's just that you didn't, therefore, because you started using these tools, jump to the front of the line. You had to do that just to be competitive, you know. And so I wanted us to talk about that too because I think it's really interesting how rapidly the playing field levels when you're talking about technology.

Dan Sullivan: One of the things is that there's a couple of quotations. One of I don't know who said this, but one of them is, "Man plans and God laughs."

Jeffery Madoff: Yes.

Dan Sullivan: So there's a lot of planning that goes into the technology world. The planning involves that the technology, once introduced, is going to gain speed. And those who are first in are going to have a perpetual advantage to do it. And there's another quote, and I think some famous general, he said, "No plan survives the encounter with the enemy." And the way that I experience a lot of the technology thinkers, because I'm connected with that world through my entrepreneurs, is there are people whose mentality is that machines are good and humans are bad.

Jeffery Madoff: Because they're inefficient?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and I would say that what you just said is the key point is that the gold standard for human life should be maximum efficiency. But one of the things I've discovered about efficiency, it doesn't leave any room for imagination. It doesn't leave any room for creativity. It doesn't leave any room for new innovations. So the very thing that created your technology has to be eliminated to achieve greater efficiency. And I think it's because there are different people who are actually in charge of the new technological project than the people who actually created it. And we've talked about that before, the difference between the number people and the creative people.

Jeffery Madoff: And I think that, of course, ideas are strongest when it's a collage of ideas and considerations. So just as what will it do is important, it's what's going to sustain this, because it's going to cost a lot of money to build this system. So is there, in fact, a business there, or is it kind of a novelty? And I think that becomes an interesting question too because there's so many things that get tremendous hype that are gone literally within a year. But they got a lot of attention.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. The other thing is that there's a certain Ponzi scheme quality to early investment, the way early investments are done, that the money is not actually made on the new technology. The money is made on being first in the big bet that's betting on technology and getting in really fast and getting out really fast. As other investors put their money in, you're benefiting from the growth of the other investors. You're not really benefiting from the productivity of the technology that's been created.

Jeffery Madoff: That's a really important point. You're right. And you and I both know businesses that appear to do really well, and the only ones that did well were the founders because they got out. You know?

Dan Sullivan: No, I use the word Ponzi because if you step back from looking at them, when are the first people in and when are the first people out? And it looks like they're out before the technology actually proves itself or proves that it isn't anything. The whole thing is to get a major portion of the first bets on the technology when they come in. One of the people who's very key to the technology world said to me once, he says, "What have you noticed in the difference of what the game is in technology?" You know, and I would say my involvement where I know people who are really involved in technology probably goes back about 15 years. And I said, well, when I started getting interested, it was about Silicon Valley and all the bright people that were generating new ideas and inventing. And at the end of 15 years, it looks like Las Vegas.

What you want to be is the house so that you can take advantage of all the gamblers. And my sense is that in all industries, there's a house who really profits from the increased engagement and the increased investment of a lot of people, but they're taking no risk at all. They're always, and you know, in Las Vegas, it doesn't matter, minute by minute, they get a percent of all the money that's being gambled. And I think that maybe all industries take on this form after a while, that certain smart people say, well, where's the money really being made in this industry? And it's not in coming up with new ideas, it's taking advantage of other people being enthralled by new ideas. I think religion took on that form after a while. I mean, the Vatican's a very expensive building.

Jeffery Madoff: Yeah, and the clothes are pretty damn fancy too. That's true. You know, religion is fascinating in the sense that you never actually have to deliver anything. It's just, "Have faith."

Dan Sullivan: Having been involved in it more deeply than you, I would say that there's sort of peace of mind that gets delivered. There's a sense that you have the easy pass and other people don't have the easy pass. There's a lot of confidence building that's actually built into religion, you know.

Jeffery Madoff: Yeah, and I think, though, if you haven't achieved peace of mind, it's because you have done something wrong, which is a great business model. "Sorry, we don't take returns. There's no refunds on this."

Dan Sullivan: Well, let me ask you a question. I mentioned that I saw the technology world taking on the character of Las Vegas. Do you see the technology world taking on the character of religion?

Jeffery Madoff: Oh, yeah. Absolutely.

Dan Sullivan: Because I think this is really key to what we're talking about here.

Jeffery Madoff: Absolutely. You know, I think to our peril, there have been people, be it Steve Jobs, be it Elon Musk, there are people that have taken on almost a deification by a certain level of consumers. And even in politics, now this current term, you know, we're in a heated, polarized time, and there are many religious references: "The Redeemer," "I'm your protector," "God intervened," and all these kinds of things. And I think that doesn't bode well for anybody. And I think that the deification, I think Jobs, Musk, many of the people who are deified in that realm is there's a big connection between extraordinary financial accumulation. And, you know, on our money it says, "In God we trust." I think that's not an accident.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Also in creative things that really work too. I think that there's a certain magic quality to new technologies that really work. Probably the culmination of the Apple development over a 30-year period was really the iPhone. The iPhone really works. It works in any way that you want to make it work. So it's sort of a magical instrument in a lot of ways. I mean, we've grown up with it, you know, we've gotten used to it. But if you hit the 2024 iPhone, the way it exists today, and that was possible for you in 2000, you would think that it was sheer magic.

Jeffery Madoff: Yeah, well, anything that we can't explain falls into the realm of magic or religion. And what I'm saying is nothing against religion, but it's how we as humans cope with things that we don't fully understand, or explain things we don't fully understand, or wanting something that seems to lay out both the important questions and the answers. You know, and AI falls very neatly into that category. Because at the same time, there's a growing generation of makers. And those makers are people who are rejecting 3D printing, computer-generated designs, which is kind of a form of AI that's been going on for quite a while now. So it's interesting as some of these people who are in our age group and even a bit younger are closing up their factories that young people didn't want to learn that craft anymore. Now they're being bought up. It's quite interesting. A lot of it's happening in New York in the garment industry, as a matter of fact. Luxury markets are experiencing some business contraction. Fast fashion businesses, which are huge, like Zara and Forever 21 and these kinds of brands, that instead of younger people wanting to buy that mass market merchandise, I think the new luxury and the new desirability comes from something that has the human touch.

Dan Sullivan: I agree. I was talking, interestingly enough, this topic came up at a cottage party that I was at last night. And I said, you know, there's very definitely a retro movement in terms of what people are seeking out in terms of purchases. For example, they're starting to notice that certain cars from 20 years ago that were well designed and they were popular at the time, but then they were replaced by newer models. There's now a huge market for buying these cars and repairing them, making them new again. And people say that, and it's very psychological and I think it's very emotional, that you can get so far into the world of new that you've lost touch with everything that already exists. The phonograph records, the hi-fi phonograph records, there's a huge booming industry now. One of the people at the party last night has invested in a company where they've created a new kind of vinyl that doesn't scratch, so that the needle won't scratch. But the other thing is, the actual recording process puts more sound into the vinyl than it was before. And he says there's a huge market. He says when this guy first started, he might get an order every month from somebody who wanted to do that. And he said now he can't keep up with the demand that people want to hear recorded music coming from vinyl rather than digital.

Jeffery Madoff: Yeah, that raises a few things to me. I know that percentage-wise, that's a rapidly growing industry. It's still a small part of the overall, but it's growing very rapidly. And I believe that materiality, something that you can touch, hold, share... For instance, I was watching this documentary on the Beatles on the Abbey Road Studios, which is quite fascinating, the history of Abbey Road, which is long before the Beatles. And it was fascinating because the reputation that it had, the best equipment, the best engineers and producers and all of that sort of thing. But it also made me think about when a new Beatles album came out. That was a social experience. Without fail, seven or eight of us would get together, crank up the stereo, and listen to the newest Beatles album. And that when a new release from a group that enough people liked, and there were a lot of them at that time, it was a social experience. You weren't isolated with earbuds, you know, by yourself. And I think that we lost something. I think every time we lose the ability to connect with others, to share an experience with others, we are losing something fundamental to what we are as humans.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Which brings us back to our kickoff topic for today of theater, that theater is the ultimate in a shared emotional experience because it's live. You know, it's not recorded. It's taking place right now. And it has all the energy and all the risk of something that's happening right now. And I think the more the world goes digital, I think the more the world craves theater. I'm not talking strictly theater that takes place in theater, but theatrical experiences that take place in life.

Jeffery Madoff: Right. Right.

Dan Sullivan: Like having a great evening and a conversation with just the right people.

Jeffery Madoff: Yes. Yeah. And, you know, drama just doesn't refer to something that happens on the screen or on a stage. It can happen around that dinner table. It can happen on the job, you know, and, there's something very much related when there are young people, people in their 20s, who are in a sense, not in a sense, they actually are apprenticing in some of these leatherworking shops, millinery factories, and there's a kid who just got financing to take over this major leatherworking plant in Brooklyn. And his stuff is being bought by all kinds of stars and all that sort of thing, which gives him great publicity. But if he wanted to get back to that craft, that artistry, that human touch, and it also creates a product that's unique. The grain and the leather is never the same from the same style. There's something different.

And in a time where things are so mass-produced, and even those mass-produced items, by the upper-tier designer names are ridiculously expensive. And I much rather have something- I enjoy clothes, they're fun. I much rather have something I'm not gonna see everywhere else. Because why do you dress in a certain way? It's either to blend in or you enjoy standing out, theater, performance, wardrobe, all of those. Ralph Lauren would say that he doesn't design clothing. He said, "I write through my fashion. I tell stories through my fashion." And he doesn't know how to drape. He doesn't know how to draw. Yet he knows how to create a wardrobe for lifestyle that tells a story.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And Ralph Lauren has, you know, all of his merchandise, because in Chicago, it doesn't exist anymore, it didn't survive COVID, but they had a restaurant and I think they had one in New York too.

Jeffery Madoff: They do.

Dan Sullivan: I don't know if they still do, but...

Jeffery Madoff: Yes, they do.

Dan Sullivan: ...the one in Chicago is gone because that whole Michigan Avenue is going through a vast depression right now. There's as many empty storefronts now as there are active stores. But he had a club. It was very club-like.

Jeffery Madoff: I ate there, actually. It's wonderful. It was really cool.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, it's like a '50s club. But if you go through the merchandise section, the clothing, the furniture, and everything else, it's from the '40s and '50s. I get a feeling very, very much. And I think he had a feel right from the beginning that there was a retro kind of period in—certainly in American history—that there was a sense of style, there was a sense of glamour that got lost after the digital technology started taking over the world in the '70s and '80s and '90s. There was something personal that was being retained in this type of style that has been lost in the digital age.

Jeffery Madoff: Yeah, and I think there's other factors too, but as you know, Ralph was a client of mine for 38 years, and I worked directly with him. And, you know, as I mentioned, he said he writes through his clothes, but what he did as a young kid, and when I did- He got a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Council of Fashion Designers of America, and it was at Lincoln Center, and I created the film that was introduced by Audrey Hepburn. So for who I met, who by the way was as lovely and wonderful as you would hope she would be.

Dan Sullivan: And classy.

Jeffery Madoff: Total. Total. You know, the word icon is way overused, but she was iconic. You know, she deserves that title. And to Ralph, he wasn't getting a fashion award. He was getting an Oscar Lifetime Achievement Award. And the person who he watched on that screen, Audrey Hepburn, along with Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn and Gary Cooper, that these figures dressed in a way... He didn't see suits that had that kind of peaked lapel in stores that he could buy them. And it's like, God, these people look so great. I want to dress like that, you know. And so it came from, that was his escape. You know, he was a kid of Russian immigrants, had his nose pressed up against the glass of Brooks Brothers and these other, what used to be, you know, the where the wardrobers for Madison Avenue and Wall Street. And the movies were his escape from a life that kind of marginalized this young Jewish kid.

And he built an empire. It was his imagination. It was his creation. It was his unique connection and forming the bridge between our fantasies and the product he could offer, which was, you know, when you think about what he did, it was really masterful. And it was all based on human connection. And, you know, everything he did, you go through his stores and it's like, you know, the stuff that's part of the decor, actual antiques and paintings and portraits of those movie stars and all of that, you know, you wanted to be a part of that world. And he was so effective at creating it. It's really fascinating because nobody did what he did better in terms of creating a fashion brand. And it's all about storytelling. It's all about theater. It's all about connection.

Dan Sullivan: I've been following the whole study of human consciousness, right about the same time I got interested in the microchip, because of the predictions that these technologies were going to take on human-like quality down the road. And I said, that would be really interesting if we knew what human-like quality actually was. And the more and more technology goes forward, it seems the less grasp that they actually have of what a human-like quality actually is. And so where this all starts is really with Galileo, and Galileo consciously said there's two parts to human thinking, and one of them is mathematical. And he said, we can make extraordinary, fast gains if we disassociate the mathematical part of human thinking from what goes into the arts, what goes into music, what goes into literature.

He said, both of them make part of human thinking, but he said one of them is measurable and the other one isn't, so why don't we just separate that whole non-measurable part of humanity, put it off to the side, and just concentrate on everywhere where we can do measurements? Well, we're now at the 300-year mark since he made that distinction. And he didn't mean to ignore it. He simply said that there's progress that you can make just by measurement. Well, not many people in the technology world can tell you who Galileo was and how long it was. And they've created a world where there's only measurement. And measurement leaves out 99% of what makes up human experience.

Jeffery Madoff: And that measurement, the reason for the measurement, it's interesting, and I don't have this thought fully fleshed out, but it just, you know, you inspired this thought, is the reason for measurement is comparison. That's the only reason you measure. And I'm not saying that's good or bad, how it's applied can be good or bad.

Dan Sullivan: The only way we can do measurement is through…

Jeffery Madoff: Measurement.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. No, the only way we can do comparison is through measurement.

Jeffery Madoff: Right.

Dan Sullivan: Well, there's qualitative measurement, there's qualitative comparison too. I would say the easiest to come is quantitative.

Jeffery Madoff: That's right.

Dan Sullivan: But where that becomes the overriding, dominant thought for everything that involves human society, you're hitting a wall.

Jeffery Madoff: Yes. And I also think you're hitting a wall... Well, why do you think we're hitting a wall?

Dan Sullivan: Well, I think hitting a wall is that, out of the belief, and I think it's a religious belief, that at some point we can transcend ourselves, that we'll create technologies that transcend humanity. And that strikes me as a religious belief. That's not a scientific belief. That's a religious belief.

Jeffery Madoff: I totally agree. I totally agree. And my question about that is, why is that desirable?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, why do you want to do that? I mean, get a date, you know?

Jeffery Madoff: Yeah, buy one of those Japanese sex robots. I mean, come on.

Dan Sullivan: No, take in a show, get a date, you know? Why are you doing that? But I think it's from a profound unhappiness of who you are as a human being. And you're not in the technological realm here, you're in the religious realm, you're in the philosophical realm, you're in the psychological realm. This is not technology or mathematics or science or anything like that. You're in a completely different realm. But you're seeking the answer for an experience you're having over here. You're seeking an answer using a methodology which can't give you any insight on what's actually happening to you.

Jeffery Madoff: Well, yes, you're correct. And, you know, you mentioned happiness. And I would venture to say that most people aren't happy. But first, one has to define what is happiness. And how would you define happiness?

Dan Sullivan: Well, I think one aspect of happiness is liking who you are in the experience. You kind of like who you are right at this moment in this experience that you're having. And I think that all people have zones of happiness. It's certain activities they're doing or it's certain, you know, relationships that they have with other people where in fact they are happy, you know. I don't think there's any general happiness meter that you can apply to human beings because I think it's entirely subjective and, therefore, it's not measurable. But I think a lot of it has to do with feeling very good about just who you are as a human being.

Jeffery Madoff: I think you're right. And there's a professor who teaches happiness at Harvard. His name's Arthur Brooks.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, I've read a lot of Arthur Brooks.

Jeffery Madoff: Yeah, and his claim is that happiness isn't a feeling. That feelings are evidence of happiness. And he compares it to the smell of turkey is the evidence, if you will, of Thanksgiving. But it's not Thanksgiving. You know, just like the feelings are the evidence of happiness. And that real happiness mixes these momentary pleasures with the satisfaction of the sense of your life having some kind of meaning, essentially what you're saying, which I agree with, because I think if you're not happy with who you are, what really makes you feel good about being you, you're not going to achieve happiness. And it's also transitory.

Dan Sullivan: I had a client who was on his fifth marriage over about a 25-year period, and he asked to have a lunchtime conversation with me at one of the meetings, and he said, "You know, I don't know, there's just something missing. There's just something missing. Every time I get married, I think this is it. And it turns out not to be it." And I said, "Well, I mean, can I ask you a question? Of the five, are they all the same kind of woman? I mean, are you just trying to, you know...?" No, they said they're very different. Age-wise, they're different. Shape-wise, they're different. Personality-wise, they're different. And I said, "Well, if you think about all five, you're on your fifth right now, is there any common factor to these marriages? I mean, something that's always there?" And then he said, "Oh, you don't mean me, do you?" And I said, "Well, I'm just asking the question about common factors." I said, "I'd be open if there were four or five others that we could discuss, but it seems to me you already did the elimination process. There wasn't anyone." And I said, "I don't know, maybe the marriage failure has something to do with you."

Jeffery Madoff: "Not a chance. Not a chance. Yeah, it wasn't me. That bitch and I still get along. No, it wasn't me."

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, but the big thing is that I've been reading recently, because there's a lot of literature on the internet right now about consciousness, and there's been no progress whatsoever in science understanding what consciousness is, nor can there ever be because consciousness is purely a subjective experience that's not measurable from the outside. And that's the wall that science is hitting. The thing that created science can't be examined. In other words, it was human consciousness that created science all along the way, but the creation can't measure the creator. And I think there's a profound unhappiness in the technological world, in the scientific world, that they've hit the wall.

Jeffery Madoff: Well, you know, it reminds me of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein. You know, that the scientist, in hoping to play God, creates a deeply flawed facsimile of a human.

Dan Sullivan: And there was only one human who was totally involved in the whole project. Jeffery Madoff: Yes. Yes. And well, except for the guy that went out and got the wrong brain. You know, a little bit of Wizard of Oz in that, I guess, too. And it's fascinating because, yes, how do you become conscious of consciousness? And it becomes kind of a meta idea of trying to define it.

Dan Sullivan: But I think we do. I think we do.

Jeffery Madoff: We do what?

Dan Sullivan: Become conscious of our own consciousness. I think we do.

Jeffery Madoff: Yes. Or are we conscious of our own feelings?

Dan Sullivan: I've observed in doing podcasts with you and writing the book that at certain points, I can see your eyes and you're actually looking at the thoughts that you're thinking. I think that's consciousness of being conscious.

Jeffery Madoff: Oh yeah. I mean, you know, one of the things that I so enjoyed about my philosophy and psychology major, studying those two, is because those two made tremendous sense to me as one discipline. And, you know, it was interesting that up until 1932, philosophy and psychology were the same entry in the Encyclopedia Britannica. And then when Freud was asked by Britannica to write the entrance, the first-ever entrance, on psychology, that forever separated the two disciplines, which was kind of interesting.

And I think that, you know, thinking about thinking, which is something else that you and I share, is something we both really enjoy, the exercise of thinking about thinking and why do you think that, you know. And as it relates to happiness, I think that happiness requires work because it requires, I think, one to have a sense of purpose, which can give a sense of satisfaction, and that satisfaction can breed happiness. And that's another way of saying what you said earlier, which is that you're kind of at peace with and know who you are and are comfortable with that.

Dan Sullivan: You know, in Coach, we created this model which is called The Gap And The Gain. Okay. And what I show in the book is just, you know, a human head. And I said, there's an interesting thing we do when we measure progress. So, progress always starts is that you have a picture of the future and then you establish a goal which will be a measurable achievement that in your thinking will move you closer to what it is that you want to achieve. And you can just use your theater experience of the last six or seven years to say the achievements of jumping ahead into the future.

And we were talking about Personality, the play, before we started the... What you're doing now, you're into the auditioning process for the opening of the play in London, in England. So I said... And all human beings do it the same way. We see something in the future and we pick an achievable milestone ahead of us, that if we do this, this will move us closer to what we want, we think. And energetically, we feel that. So it's a sense of energy, it's a sense of confidence, it's a sense of progress. But I said, all of us have achievements, but we divide ourselves between what we measure the achievement against. And I said a lot of people measure their achievement against an ideal they have, and it feels to them that they've made no progress at all because ideals are not measurable.

Jeffery Madoff: Like trying to make a photograph of the close-up of the horizon.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, I actually used the horizon that, I said, when was it as a child, did you become emotionally and psychologically okay that you couldn't reach to the horizon? It doesn't matter how fast you are, it doesn't matter if you do it at night, it doesn't matter, you're never gonna reach the horizon because the horizon actually doesn't exist. It's simply a mental structure that we have to account for the curvature of the Earth. So I said, but the other way, if you measure your progress of an achieved goal against the ideal, you'll never make any progress. In your own mind, you'll never be making any progress. On the other hand, when you have the achievement, you turn around and measure backwards against where you started, you feel tremendous progress, you feel tremendous accomplishment, tremendous confidence. And I said, the two ways of measuring is what separates all human beings. And I said, when people are happy, it's because they're measuring backwards. When they're unhappy, it's because they're measuring against an ideal.

Jeffery Madoff: Right. When we first talked about that in one of our many, many conversations, that notion, which I think is a tremendous insight on your part, which is that measuring yourself against where you were, as opposed to some kind of vaporous ideal of where you should be, that you're never gonna be happy. Because it ultimately seems like, again, back to the horizon, like you're trying to shoot a closeup of the horizon, but no matter how close you move to it, you don't get any nearer to it. And I think that's, that's the thing is, looking at yourself. Where was I in... Using the play, where was I when I started this process? Where was I the first year, then the second year, then the third year? And where has that gone?

And I feel very good about the progress we have made. But it's I'm feeling very good measuring it against myself and the enterprise, not some, well, we haven't won any Tony Awards yet. We haven't had a Broadway opening yet. We've already achieved more than most plays did. But I think if you're an Olympic athlete, you've got the clock to measure yourself against. But you're the smartest when you measure yourself, your own performance against your own performance. And ultimately, then you're not competing with anybody else. And I think there's something of value that's not Pollyanna about that at all. It's a way to think about things so you're focused on achievable results and you can look at that distance that you've traveled to get to where you are, like even qualifying for, in this case, the Olympics, and give yourself a pat on the back. Feel good about what you have done as opposed to feeling bad about what you haven't achieved.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. So my sense is that the number one enemy that the technology people are running into right now is actually called humanity. And in order for them to jump to the next level, they have to give up their humanity. And I see a lot of them doing that. And it slips in. And I said, why do you hate human beings so much? What was it? What was the incident? You know, like that. But there's almost this hatred of humanity because humanity cannot be defined by efficiency. The concept of efficiency leaves out 99.9% of what constitutes humanity.

Jeffery Madoff: And fun.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. The fun is not on the efficient side.

Jeffery Madoff: No, it's not.

Dan Sullivan: If you want to come into the efficiency bar, you got to check fun at the door.

Jeffery Madoff: That's right. And so I think that then ties back to one's notion of happiness. You know, how do they feel about themselves and whatever purpose they've laid themselves out? This doesn't have to be purpose in gothic print, you know, but it's having an idea of what fulfills you, what's gratifying to you, what do you feel good about. And I think that also all comes back to human connection. Without human connection, I don't care how smart you are, I don't care how accomplished you are, you are in some profound way broken.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and I think the whole thing of human connection is really that you're bigger than your own experience, as you're including other people's experience in your experience.

Jeffery Madoff: Right. And sharing that. That's right. That's right. So I think it's really fascinating because my sense is that there are always people that go back to certain basics, if you will. This whole maker's movement, which is not insignificant. You know, I would rather pay $1,800 for a pair of custom made shoes where they have my last, and it is perfect and comfortable and unique in every way that I like than to, you know, buy a pair of shoes-

Dan Sullivan: Those are the ones with the steel toes, right?

Jeffery Madoff: That's correct, that I can plug in. [laughs] But you know, I mean, the thing is, you know, I don't think luxury is having lots and lots and lots of stuff and the ability to buy lots and lots of more stuff. It's about having something that is for uniquely you.

Dan Sullivan: And you love it.

Jeffery Madoff: Yeah. And I think that's really an important factor in it. And you're right that AI is putting us up against who we are. So, what's in the reflection of that mirror? And those who say, well, this is going to eliminate a lot of the dull, repetitive tasks that are done. I mean, look, it's great to be able to have an automated calendar or something like that. I think we're often striving for things that, as we were saying earlier, is that really a desirable thing to achieve? What's the singularity?

Dan Sullivan: I think it is that when you've removed all human elements from the technological striving—in other words, that you're more and more, we're not going to depend upon human beings, we're going to replace human beings—you get to the point where you realize you've eliminated all the human beings except one.

Jeffery Madoff: Yourself.

Dan Sullivan: And I think it's, I can see some very suicidal tendencies in the part of a lot of these tech people.

Jeffery Madoff: Well, we are seeing that.

Dan Sullivan: No, no, I'm seeing it. I'm seeing a lot of it.

Jeffery Madoff: Yeah. And you know, the, I don't know if this is still true, but it was true just a few years ago that the highest income swath of residencies for Silicon Valley executives had the highest suicide rate in the United States. And it was often kids.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, yeah. Yeah.

Jeffery Madoff: We're seeing the growing body of evidence in terms of the toxic nature and effect of social media. You know, and because we can do something doesn't mean it's worth doing. And I think that that becomes another big issue because-

Dan Sullivan: Or it's not worth doing twice.

Jeffery Madoff: That's right. Yeah, I did that once. That was enough. Don't need to do that again. That's right. But it is, I mean, you know, when the goal is productivity, efficiency...

Dan Sullivan: Well, I think efficiency is the killer. It's not so much productivity.

Jeffery Madoff: Yeah, I agree with you.

Dan Sullivan: And the reason is because by its very definition, productivity involves the human being. Efficiency doesn't require a human being.

Jeffery Madoff: Well, that's true. In my conversations with Eli Whitney, he told me that when he was making the cotton gin. [laughs] "You just have fewer people in the fields, we can make a little more money." "But you're not paying them anything. They're slaves." "Well, it's all right, we can make this more efficient." You know, which, by the way, although I was just making a joke, a dark joke, that's actually, I think, a truth, is that what is the goal of the efficiency? As you've said, it's dehumanizing. And that's exactly what the early attempts at efficiency were doing, was dehumanizing a group of people. You know, so there's real-world examples throughout history of what you're talking about.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, a lot of people think the most consequential invention of the 19th century was the McCormick reaper. And the McCormick reaper replaced 16 people who were reaping, you know, cutting wheat and everything else. So one farmer with a reaper and a horse could replace 16 other human beings. Now, here's the thing. It wasn't great work. It was backbreaking and very punishing work. And that freed up those workers to go off and do all sorts of other things. So there's a second phase to it. You grew up in Akron and a lot of, say, 30 years before you, those who went to high school in Akron worked in the rubber factories. And you didn't. I don't know if it was still growing when you were growing up or it had reached its peak and it was starting to go backwards.

Jeffery Madoff: I don't know when that peak was because all the factories were-

Dan Sullivan: I suspect it was probably late '50s, early '60s.

Jeffery Madoff: Maybe a little later than that, but not much. I think you're right. I don't really know for sure, but I think by the… I don't remember. I was going to say late '70s or so, I think a lot of the factories had moved out. The offices were still there, but the factories had moved out. I think that the question to ask is, what is the potential effect of this? Is that desirable? So the McCormick reaper, this could free up people to do other things that weren't as punishing work or a different kind of work. Is that worth doing? Well, it saves us money. It saves their spines. Yeah, this is something that is worth doing. And so I think the question of, "Is it desirable? Is there a desirable outcome?" is an important question to ask.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and I think you have to ask that for yourself. Do I even want to be involved in this, you know? With 80 years behind me, I'm more and more realizing that different nervous systems approach experience differently than I do. You know, we do different things with our experiences, and more and more I'm interested in the difference of how people handle their experience than that they handle it the same way. That's not really interesting to me, is that they deal with it differently and they come up with other lessons and they come up with other insights about their experience.

Jeffery Madoff: Yeah, I've reached that same point too, where I might, some years ago, have been more interested in a debate about those things. I'm much more interested in just, "That's really interesting. Why do you see it that way?" Because that opens the door to learning and actual communication, as opposed to shutting people off who don't believe the same thing you do.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Debates just cut down on the number of people that you can associate with.

Jeffery Madoff: Yeah, which isn't a bad thing in many cases. [laughs]

Dan Sullivan: Anyway, what new have you picked up or new ways of thinking from our discussion today?

Jeffery Madoff: Well, God, there I think there was a lot here. It's funny that, again, you and I sort of struck on the same topic of what to do. But I think that the main thing is the notion of how the more efficient, the less human. And to me, the less human, the less desirable that outcome is.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Well, the more efficient, the less human, and the less human, the less purpose for the efficiency.

Jeffery Madoff: That's right. That's true too. Very good. That's true too.

Dan Sullivan: It completes the circle.

Jeffery Madoff: That's right. What's- Maybe you just shared the insight you had.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. It just seems that at a certain point, you're cutting off all the rationale for doing what you're doing. Because if you're not doing this for the benefit of humans, then I can't think of a single other reason why you're doing it. You know, that's good. I mean, that would be a good reason.

Jeffery Madoff: And I also think another thing is, in terms of trying to understand what happiness is for you as an individual and realizing that I believe it comes from a sense of purpose and connection to others. And the resulting... I like the idea that, like, the smell of turkey is the evidence of Thanksgiving. Of course, turkey's not just restricted legally to Thanksgiving, so you can be fooled. But I think that the core we were talking about is that you have to be comfortable with yourself before you ever achieve a sense of happiness.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, comfortable and actually liking, you actually like who you are. Yeah, I felt that way... I don't think I felt that way at 60. I felt a lot more that way at 70. And at 80, I'm pretty well in the zone that I just kind of like who I am, you know, like, it's just It's kind of cool being me, you know. And I think you feel that way too. It's kind of cool being you.

Jeffery Madoff: Yeah, I do feel happy about that. I feel the relationships that I have, those connections that I have, the connections you and I have built with each other. Would I have known that was going to happen? No. Was the openness that you and I share independently, did that create that possibility? Yes. And that curiosity and sense of discovery? And along the way you discover who that other person is and the potential for that connection, which can be, which can feel so good.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Yeah. You know, I don't know how you would prove this, but we may be the two happiest podcast partners in the world.

Jeffery Madoff: [laughs] I think our belief, and even thinking that, is evidence that you're correct.

Dan Sullivan: [laughs] I mean, the key to good podcasting in a partnership is the same as improv, is that you never say no to what the other person brings up, and you always help the other person out. That's how improv works. Two rules. You never say no. You never block or stop or negate or argue with what the other person brings up. And you always help the other person out by adding more to what they've already contributed.

Jeffery Madoff: That's right. Somehow, Dan, I don't know if that was conscious, but that relates back to theater and the experience that is essential to being a part of humanity.

Dan Sullivan: No, I think the reason why we're getting such instant understanding of the title of the book is that theater is archetypal.

Jeffery Madoff: Yes.

Dan Sullivan: Humans are born with this archetype.

Jeffery Madoff: Yeah, that's right. And I think when you can create something in that way, whether it's the hero's journey, when something is understandable and understandable in concept, essentially instantaneously, I think that can be pretty profound. So did we stay within our boundaries of anything and everything this time?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I actually think we left a little room within the boundaries today.

Jeffery Madoff: Like how much?

Dan Sullivan: We're pretty consistent of touching with what the original thought was. I think that was very good. But I'm seeing this more and more, and I'm gaining more and more article evidence that there's a profound uneasiness in both the scientific and technological world, that they've hit walls, that they're not making the progress that they were making before. And I think it goes back to the separation that Galileo made hundreds of years ago. There's two ways that human beings think about. We're going to take one of them and put it to the side, and we're just going to focus on this one.

Jeffery Madoff: Well, I think it's something else too. I think it's the gargantuan growth of companies that used to be innovative, but now they either acquire or buy that innovation, which stifles innovation or stifles competition. You know, because a lot of companies get bought to kill them because they represent a potential threat. And that in and of itself is... I think that they're hitting a wall because the question becomes, why do I need this? You know, what's desirable about that? I mean, this whole idea of, you know, that we will eventually be able to transcend and blend the world's knowledge into a chip that we can implant, that sounds horrifying to me. What's desirable about that?

Dan Sullivan: Or the chip just gets rid of us.

Jeffery Madoff: That's right. [laughs]

Thanks for joining us today on our show, Anything and Everything. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend. For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

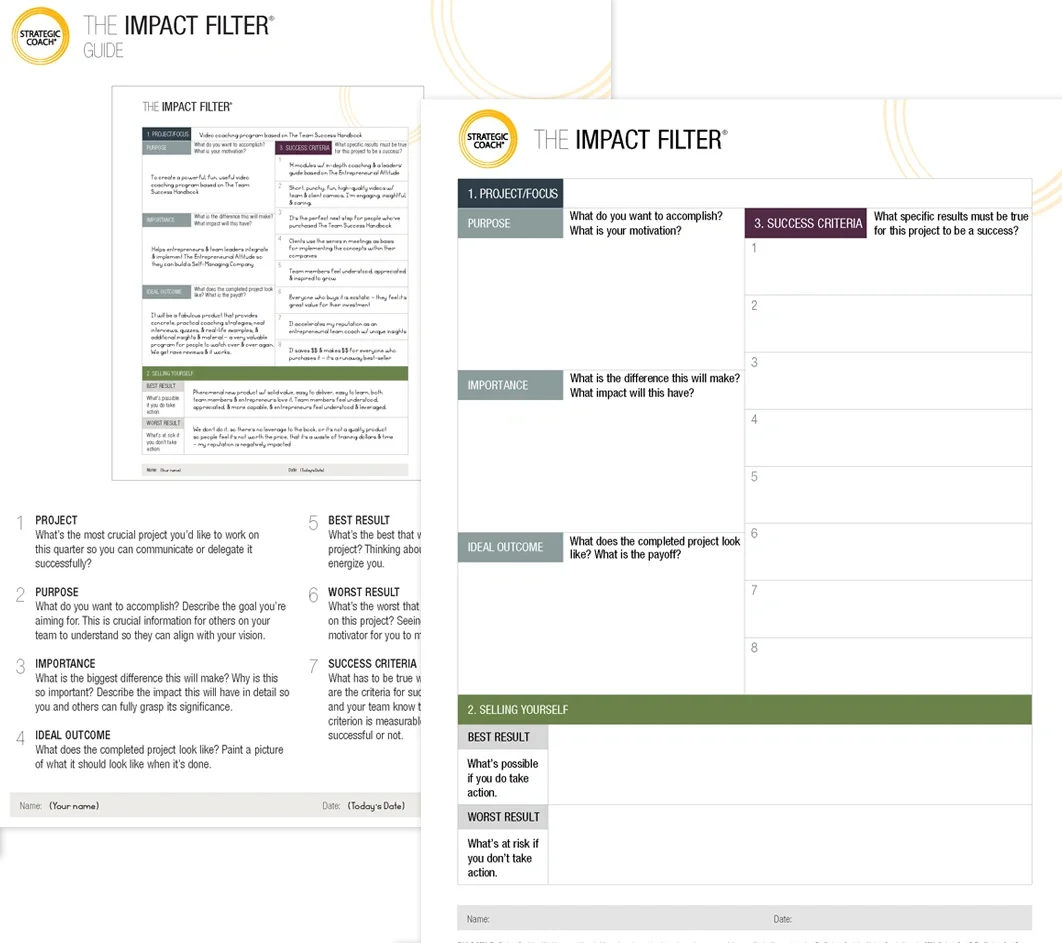

The Impact Filter®

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.