What Clicks When You’re Casting

December 30, 2024

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

Do you recognize the unique strengths of your team, or do you overlook them? Jeffrey Madoff and Dan Sullivan explore the art of “casting” in business and life, revealing how self-awareness and understanding can lead to greater success. Discover how knowing oneself can transform team dynamics and drive long-term achievement.

Show Notes:

- There are a lot of talented people out there who are compelled to do what they’re doing.

- When someone’s auditioning for a role, you get a gut feeling if they’re nailing it or not.

- Someone having the right appearance for a role doesn’t mean they can pull it off.

- Some talented people can take direction, and some can’t.

- In addition to skill, you can test someone’s instincts in the audition process.

- Sometimes, you find out that someone you called in to audition for one role would actually be good in a different role.

- For a person to be the right fit, they have to be both good in their role and good in teamwork with everybody they’ll be working with.

- While you’re casting, you have to be focused, and aware of the context of the role.

- The more casting you do, the sharper your casting skills become.

- Finding the right person for a role might require a lot more looking than you’d hoped for.

- The higher your standards, the longer it might take to cast someone in a role.

- Greatness is only achieved over a long period of time.

- If you know who you are, you don’t have to spend time thinking about it.

- It's hard to care for others when your full-time job is caring about yourself.

- If someone doesn’t know who they are, you can’t predict how they’ll respond to challenges.

Resources:

Book: Casting Not Hiring by Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff

Book: Wanting What You Want by Dan Sullivan

Learn more about Jeffrey Madoff

Dan Sullivan and Strategic Coach®

Episode Transcript

Jeffrey Madoff: This is Jeffrey Madoff, and welcome to our podcast called Anything and Everything with my partner, Dan Sullivan.

Dan Sullivan: We were just chatting because you are involved again in taking your becoming a Broadway musical to next level. And we were talking about auditions and we were talking about casting and we had just completed a book together, which will be out in its first form in September called Casting Not Hiring. And we were just talking about what is it that really clicks when someone gets a role? And I'm not talking just about a theater role, but life role. In life, we have to play particular roles in relationship to our personal life and also to our business life. And so, Jeff, what's your sense? Because you're just fresh back from your auditions, and these were really compacted. You had to do an awful lot in about four days, I think, to fill 18 roles or 14 roles? I'm not sure. 18 roles and you had to do this with not much time to spare. What's it done to your thinking about why someone clicks?

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, to quickly just explain the process. The first thing that happened is that Sheldon Epps, the director, and I were sent where they were available video clips aside from the resume and still pictures of the actors. It's a, not a great way to judge people, but we use that as an initial filter. With the caveat, as we told Pearson Casting, James Pearson, that if there's somebody we say no to that you think we should see because we're going on very little, we'll see them. So if you think we left somebody out that we ought to see, invite them in. And then we had very packed days where we weren't just auditioning the acting, we were also auditioning singing and dancing. And the overarching thing that hit me was, God, there's some wonderfully talented people out there. And as I mentioned to you before we started, thank goodness against all odds, they're compelled to do what they're doing. And that brings a lot of joy to the world through the arts and performance and so on.

So what makes somebody click is an interesting question because it's not necessarily, well, I don't think not necessarily is even close. How can I say this? It's a gut feeling that you have about somebody that they either nail the read, but there's people you root for, by the way, there's people you root for who look like you hope that character would look but they don't have the chops to go along with him. I said to Sheldon at one point, God, this guy looks so right for the part. I was rooting for him. And Sheldon said, yes, so was I. But we both said, okay, go to work. So it's so interesting how people enter the room, how they also, and Sheldon does this with anybody that he's interested in, is he'll give them a direction: “So I'd like you to do this again, but I'd like you to explain the context a bit more,” to see how quickly they can adapt. Some people, they just do the same read and you realize that you could give them the direction 10 times in a row. They just don't have it. And there are other people that are able to just pivot and give you a different performance, a different color, a different read on that same bit that you read. And you know that they're directable, that they can do it, which is a big thing, of course, to a director. They want to know that that talent can take direction, but also how are their instincts? You know, how do they approach the part?

And I'll add one other thing is when they do the initial audition, they bring in their own music. When we had callbacks, we asked one of the women who was auditioning to play Irma Franklin, who sings “Peace of My Heart.” Two days later, when she came back, she had learned that song and blew us away with it. So it's a combination of things. Do they look right? Because that can throw you off from the beginning. If they don't look right, if it's just, you know, a young Lloyd is six foot two and Lloyd is gonna be about five nine, then you just know it's not gonna work, whether they're a really good actor or not. You know, there has to be that physical aspect. So it's a whole combination of understanding the context of the part. And sometimes, by the way, that that person may not be right for the part that you've called them in for, but they'd be really good at that if you find that out.

Dan Sullivan: Jeff, in the four days, what kind of zone do you have to go into? Because you're determining a lot of things in a very short period of time. And I'm just wondering, how do you have to be during that? You gotta be 100% right there when you're doing this, because you're evaluating many different factors and you're putting together you know, a future date when something has to be right. And the script that you have has a lot of different dimensions to it. And you're also taking a look at how people would actually work together. They'd be good in their role, but would they be good in teamwork with other actors? So how do you have to be during those four days?

Jeffrey Madoff: I have to be very focused, very present. And I'll take notes during somebody's audition. For instance, maybe they're auditioning for Dave Bartholomew, but I think, you know, they could be really, really good to play Don Robey. You know, so I want whatever thoughts like, don't forget it, jot it down, because when they leave the room, then Sheldon and I will talk. And then Sheldon, who's also in there with us, we'll say, you know, their voice is just not there for what we need or they would be great. But then we know that they're also going to have to audition for dancing, too. So we will do some sorting and review when they leave the room and not a long review. You know, it comes down to, yeah, I think they were really good. Well, let's see if they can dance or whatever. But it's about focus, really focusing, really being present and remembering the context. So if our Lloyd is five foot eight and that's the person we want to be Lloyd, young Lloyd can't be six foot two, no matter how good an actor or dancer or singer they are. You know, so there's a bunch of shadings and context that go into each of these decisions and it's just really present for it. Yeah.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, if I take you back to the reading days and first workshops that you did in New York, so that was 19, was it? I'm not sure the year.

Jeffrey Madoff: The workshop was in 2019, I believe. Yes.

Dan Sullivan: Your ability to handle an audition then compared to now.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I know auditions went back to the, you know, table read even a couple years before that, although I didn't really hold much of an audition for the table read, but we did do some. I think, you know, I've done castings before, you know, in terms of some of the film productions that I've done and that sort of thing. So this was much more in-depth because, you know, we're telling a sustaining story, not for 30 seconds like a commercial, but, you know, for over two hours. So I think that it's interesting that you ask that because I don't think that I really, probably my insights have gotten sharper. But it's nothing that I can say I really noticed because I felt from the get-go confident, for good or for bad, felt confident in my assessment of somebody's talent. And because the collaboration is so great with Sheldon, you know, we would talk about that. So I was also constantly learning from his input, from Sheldon's input, from Edgar's. But, you know, I always felt like I could recognize talent. So it wasn't like, wow, I've learned so much. I have sharpened in it because I'm doing it a lot more.

Dan Sullivan: You also, you have the advantage. You know what the play actually looks like. You know, I've seen it six times. You've, I don't know how many times you've seen it, but there is, um, a sense where anything that's discordant, you spot it, you know, it doesn't match the overall impact of the play. And so you've had dozens and dozens and dozens of the actual presentation. So I would say that your standards are much more acute right now.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's, you're right. I mean, I agree with that. And I think the other thing that I learned, as much as I may like somebody, there's no only one person who can do it. But it may require a lot more looking than you had hoped for. We're not going to compromise our standards. And the standards are high.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. So from a standpoint of, you know, being in a role, two questions occur to me. What do I want to actually do that this is a step on the road to where I want to be? And the second question is, do I actually know who I am, period, just as a person. And the first one has to do with adjusting to the situation. You know, the second one has to do with why am I doing this anyway? So the whole thing about that, and I'm wondering to what degree, because there's great actors and there's great performers who kind of fall apart as an actual individual human being on the outside. I remember I had dinner one night, and it was with Alice Cooper. I was a guest at a dinner where Alice Cooper was there, and the seating arrangement put me right next to him and his wife of more than 40 years. And he was talking about his early days in Los Angeles as a session musician. And they all stayed at a hotel, most of the musicians who were looking for work in Los Angeles.

And Jimi Hendrix was there at that time. You know, those twenties, Alice Cooper, his real name, I don't know what it is, but Alice Cooper was in his early twenties. Jimi Hendrix was, well, he died at 27, so he was in his early twenties. And Janis Joplin was there. And she was in her early twenties at that time. And he said that Janis Joplin, when they were talking just, you know, privately in the hotel, and she says, you know, I lead a funny life. Every night I make love to 10,000 people and then I go home and drink myself to sleep. And what it is, is that who she was, I mean, from her standpoint, who she was, that was satisfying and who she was, was actually what happened on stage. But backstage, it all fell apart. And to what degree does that make any difference in casting for a role for something that's going to happen in the near future?

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I mean, that's, a deep question, you know, and that goes to really deeper. You know, I would say it's a I'd say really deep, actually, because I think you're the psychology behind why someone makes the choice to do what they do. And often the simple answers, you know, which I don't believe in, but like, well, because they don't really know who they are and being an actor allows them, you know, I don't really buy into that. I don't know that the actors as a group have more problems than investment bankers. People are people and they have problems and issues and all of that. And so the successful trader may be a disaster outside of the office, but they win clients because by the financial metric, they've done well, although their marriages may fall apart and they don't know who their kids are.

Dan Sullivan: You know, so they're good at the role that pays them.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right. And one of the stories that I loved that I heard about Kirk Douglas and John Wayne and they were at a party together, and John Wayne said, I heard that you're doing that movie, I think it was Agony and the Ecstasy. It was about … oh, Van Gogh. Yeah. So Chris said, yeah, I'm really excited about it. And apparently Wayne said, why would you take a part like that? He says, what do you mean? It's a great part for an actor. It's a great part to play. He goes, yeah, but he was a faggot. And we represent a role to the people out there, to our audience. And Kirk said, you're not really John Wayne. You're Marian Morrison. And you're not really a cowboy. We're actors. And physically, Kirk Douglas was not a guy to be trifled with. So apparently Wayne took a swing at him and that was that fight ended by Kirk Douglas pretty quickly.

But I thought that was really great because that's true you know, that's true, but I think there are people like Sean Connery resisted after the first James Bond, he didn't want to keep doing that because he was interested in growth as an actor, he wanted to do different kinds of things. You know Daniel Day Lewis, arguably one of in the pantheon of the greatest actors, he became those characters for that period of time. Then he was able to move on to the next thing, but he became very much that. So I think there are people that do know who they are and are anchored in reality and realize what they're doing. And they may have a process that maybe even they get lost in a bit, but it's in service of the part. And a lot of people fault method actors for that.

There's a great story that Dustin Hoffman told me when he was finished shooting Marathon Man and he was having dinner with Laurence Olivier. And you ever seen Marathon Man? It's a great film. And are we safe? Are we safe yet? They were out to dinner and at that point, Olivier was very frail. Dustin Hoffman said to him, why do we do this? Why do we act? I mean, what is it about this? And Olivier got up very slowly because he was pretty frail at that point. He goes over to Dustin and he puts his forehead against Dustin's forehead and he goes, look at me, look at me, look at me. And then he goes back and sits down. He said, that's why we do it. I thought it was just incredible. I thought it was just incredible. And in business, you know, you see people like, oh God, I can't believe I'm blanking on his name now. He was head of GE, all kinds of accolades. Then they realized how he gutted the business after he left. So, you know, he's this like superstar in business and it was just not true. He actually wrecks the company. So he played a role very well, but he, in that role, the reality was he damaged the company because he didn't really have the capability.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, it's very interesting. I got hooked about, I don't know, 15 years ago on a British TV series called Foil's War. Do you know the series at all? Foil's War? Well, it's war.

Jeffrey Madoff: No, I don't.

Dan Sullivan: It was a great writer by new David Horowitz, British, takes place pretty well from the beginning of the Second World War to the end. I think it goes a little bit further into the Cold War, but eight seasons and takes part in Hastings, which is a seaside town, not far from Dover. So it's right across the water to France, and he's a homicide detective. In every episode there's a murder or several murders and he's a homicide detective inquiring, but these murders are taking place during a war when there's a lot of restrictions on the British public. And all the wars. So it's a double meaning with the war. There's a second world war. And then his war with higher officials, political officials, police officials who are trying to inhibit for one reason or another, his investigation into the murder. And the actor's name is Michael Kitchen.

Jeffrey Madoff: I saw him on the West end. He's phenomenal.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, So I realized I had seen him because he was in Out of Africa with Meryl Streep and Robert Redford. And he was Robert Redford's best friend. He hung around the bars and the lounges in Nairobi and Kenya. He was part of that British colonial set. But he's been in everything, and he's now in his seventies, so 15 years ago he might've been 60, 62, 63. And I said, I want to see an interview with him, three minutes for a lifetime. He's only got three minutes where he's actually been interviewed, where he's allowed himself to be seen. And what you get from him is that he had a job to do, and why would you interview the plumber when he's coming to do your plumbing? He's an actor, he's coming to do your acting, so why would you interview him? There's nothing interesting about him or his life and everything like that. And it struck me that here's a human being who knows exactly who he is and what his job is, but you do have people who don't know who they are, who are extraordinarily talented and they can pull off a big production. But then as their life goes along, you don't see them doing that again. They had the right talent for the right moment, you know, it was just the perfect meeting of them and their destiny to pull it off, but then they don't make, and he's been continuous for 60 years. Probably 50 years anyway, he's been continuous. And it seems to me that he knew what he wanted to do, but he also knew who he was.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, so that same conversation I had with Dustin Hoffman, I said to him, this is, this is, this is to your point. ‘Cause I think a lot has to do with the choices that you make. And again, although we're talking about movies and theater and so on, this is true in business, you know, very true in business. And I said to Dustin, so the first movie that I became aware of you in was The Graduate, great film. And I said, now I know you did Madigan's Millions before that. He goes, yeah, nobody saw it. So I said, so I was really curious. You did The Graduate, which was a huge hit. And the next part you have is a character who is totally the opposite, Ratso Rizzo in Midnight Cowboy. So I'm curious, was that a calculated choice so that you wouldn't be typecast? Or was that just how things unfolded? And it was funny because he gives me that, his smile goes, what's your name again? Then we shake hands. He goes, nobody's ever asked me that question, which is what I love to hear as an interviewer. And he said, all I knew was—I think he was 36 or something, 38 when he did The Graduate—he said, I know if I did another romantic comedy, my career would be over. I didn't know that I would be getting the script for Midnight Cowboy and that would be my next choice. But I knew that if I didn't do something that demonstrated my range as an actor, my career would come to a halt pretty quickly.

Dan Sullivan: What that suggests to me is that he knew who he was.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. Exactly. And that's why I'm mentioning that. ‘Cause there was a calculation there based on really what's essentially a business decision. You know, if I continue to do this, it's a very short lifespan in business. So I thought that was just, you know, kind of fascinating.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. ‘Cause the person who doesn't know who they are will then just be responding to the opportunity. They'll be whatever they need to be for the opportunity. And if it's doing the same thing over and over doing soap operas for 23 years, every weekday of the year, they'll do that because that's where the opportunity is.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. And that's a really interesting way, you know, of putting it because when I'm watching a performance and sometimes judging that performance, the ones that I can't judge are when the character and the actor are so intertwined that there's no space between them and the script. And there's other ones that I can see them reading a script as they're performing. You know, that it's just, they haven't eliminated that space. And as you said, it's the opportunity. And you know, they are their product and they need to sell themselves in order to keep doing what they want to do. But I don't think you achieve greatness that way, but you may work consistently.

Dan Sullivan: Well, I don't think you achieve greatness short range. I think you achieve greatness over a long period of time. I agree.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I agree. It's really interesting. So, how do you see this? If we go to the world of entrepreneurship, we both know people who have reinvented themselves over and over again in terms of what they're doing, what they're selling, how they present themselves, and so on. How do you see what we're talking about manifest in the world of entrepreneurs?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And we can mention names, but we won't. What I see is that they have an enormous interest, because they have to, in the flavor of the month. And they adjust themselves to what's popular. They're constantly adjusting themselves. And they're always talking about being at the forefront of things. You know, we're living in a new world and everything like that, but there isn't anything memorable about them. In other words, they didn't have an idea that just hits you. They might have a powerful idea, but it's not their idea. It's somebody else's idea. And the question is, if you knew them 20 years ago, do they look the same today, if you're just talking personally with them? I remember once I met somebody, and charming, very, very charming person. And I was talking to someone else who I'd known for a long time who also knew this new person. I said, I met somebody, he says he's an old friend of yours. And he said, no, John is someone who doesn't have any old friends. He says he'll be whoever he needs to be in the moment for his purposes, but he isn't someone that you would have a relationship over a long period of time. And Jeff, I think you, in my 80 years, are the person who could still have a reunion every year with people you were with in third grade.

Jeffrey Madoff: Which I've actually done. You're right.

Dan Sullivan: No, which tells me you are essentially the same person as you were when you were nine years old.

Jeffrey Madoff: I had a full head of hair and it was dark hair. No, I think I don't know. I guess. Thank you.

Dan Sullivan: No, no. I mean, I don't know how else to be. But I think when it comes to being human is that you count on people to be who they are. You know, the first time you meet them, they are who they are and you meet them 20 years later and they're still who they are. And I think that gives us a great deal of confidence as people, you know,

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think we've all had the experience, which is, and I love it every time it happens, when there's somebody that you haven't seen for years, and you get together, and there is no gap to bridge. You're just there. And there's other people who you don't see for years, and it's even awkward. You know, because I know plenty of people, as I'm sure you do too, who reinvented themselves, which I kind of hate that phrase, but I don't know.

Dan Sullivan: Pardon? Born again. People sometimes ask me, are you born again? I said, uh, first time did it. I said, I only needed to answer that. That's the same answer my mother just whopped. That's right. It was a success. It was a success. That's right.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, it took. It took. And yeah, my mother said, get out and you're not coming back in here. So yes, you're correct. And I'll give you a funny story about that. This is end of junior year of high school. And I get a phone call from this guy that I knew from school. We weren't particularly close friends. And it was like 10 at night, and he said, I wanted to talk to you. I said, I mean, I could assume that much, that's why you called, right? And he goes, well, I'd like to come over, talk to you in person. I said, well, can't you just tell me on the phone? And he said, it won't take long, it won't take long, and I'm not far away. And I said, all right. He comes over and he says, listen, I'm, I'm running for class president. I said, I know. And he said, you know, we can't really campaign. It's ‘cause school was against campaigning. Can't really campaign. He said, right. I know.

Dan Sullivan: And he said, but that's why I'm campaigning.

Jeffrey Madoff: So he said, listen, I'd like you to, uh, just, you know, you know, a lot of people just kind of, talk me up. That's the word. And I said, you know, I can't do that. And he said, why not? I said, because I'm not going to vote for you. So, you know, I can't do that. Then he said, you do me that favor and you'll be well compensated for it. And I said, we're in high school. What are you gonna do, give me like the crepe paper concession at the prom dance? I mean, what are you talking about? So anyway, I said, no, I can't do it. So that ended that. What has happened to him since? Became a lawyer, ran for government positions, became a politician. And it was like, you couldn't have mapped out how he was, who he was, from back in high school to 55 years later. He was who he was.

And it was funny, I'll just add a footnote to this. I would see him once every 10 years at the reunions. And when I saw him, he like, looks at my hairline, and he says, hi, it's good to see you, man, how are you? And he goes, just happy to see anybody, you know, from that class and from the past. And he goes, and he's looking at my hairline, he goes, looks like you've lost some hair. Okay, well, nice seeing you, and I exited. 20th reunion. Hi, how are you? And shake hands, and he's looking at my hairline again. He goes, now it looks like you've lost some hair. Third time, 30th reunion, he says that. And I said, you've had 30 years to come up with a better line than that. Cut your slack for 30 years. Yes, I have lost some hair. You have not gained any charm in the last 30 years. And it just struck me, he was very successful financially, but he was essentially the same asshole he was back in high school.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Yeah. I'm just trying to think my definition of knowing who you are. I don't think he knew who he was ever.

Jeffrey Madoff: No, I think he just knew what he wanted people to perceive him as.

Dan Sullivan: Yes. Yeah. Joe Polish goes a lot into narcissism. You know, he's had a lot of speakers on the subject of narcissism and I think narcissism, uh, am I even saying that correctly? Narcissistic narcissism is what you do when you don't know who you are, that you kind of create a role that gives you control.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, and I think everything is self-referential. That you live in a room of mirrors that only reflect yourself.

Dan Sullivan: And would you say that if you really know who you are, you don't have to spend any time thinking about it?

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, that's right. Because you're being it.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. No, I think that that's true.

Jeffrey Madoff: And I think that it's hard to care for others when your full-time job is caring about yourself. And so I see that too. So how do some of these people, and like the person I was just telling that story about, you've had members for decades at this point. And you have seen people who have during that period of time have started new businesses and to use the phrase again, reinvented themselves or reinvented what they do. How does one define oneself?

Dan Sullivan: You know, I mean, first of all, my actual answer to that question, uh, very few, very few, I've coached 7,000, you know, where I was the coach 7,000. This is over 50 years and I can name probably on two hands the people who actually stopped what they were doing and started doing something completely different and new. And part of the process that I have is that this is your whole thing that you do as a company. You're an entrepreneur and this is the whole thing you're doing, but it's not everything that you're doing that attracts you to what you're doing. There's something in the center. So I keep getting them smaller and smaller, focus down to what it is actually. Okay. And use my example. I was very interested in theater, but I wasn't interested in theater as theater. I was interested in theatrical principles that could be applied to business. And probably the best clarification of that really came from our writing the book Casting Not Hiring.

But there's something in theater that I really, really love, but I wouldn't want, you know, I had about a five year experiment of being in theater and a lot of neat skills, a lot of neat understanding on how you put things together, but it wouldn't have taken me very far if I'd actually got involved in the profession. Okay. But I wanted to take people's everyday experience and transform it into experiences that they could get where, they could learn what, where they were actually about. So my last 50 years have been about, tell me about your experience and then I'll ask you about your experience. Like earlier in the podcast today, I said, think about who you are when you're doing auditions today and who you were when you just did the very first production, when you put it on. And I wanted to see if you could see a lesson in seeing. And you said, well, I'm a lot sharper, my standards are higher, you know, and everything else. I said, that's a successful presentation. You just saw something that you didn't see before.

So, I'm kind of using theatrical principles, but I'm doing it in sort of a philosophical way. And I do that with all my team members. They said, gee, this isn't working. I said, what about it actually did work? So I said, let's put this over there. And I say, now that you've seen what did work, do you have the confidence to say what didn't work? And they put that over there. And I said, now looking at the two piles, if you were to do something different in the future, what have you learned from the two piles that tells you how you're going to do it better in the future? I didn't tell them a thing about what to do. I just took their experiences, broke it down into two piles and said, which pile do you want to keep in the future?

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, which is great because without active engagement, which is what you foster, nobody's gonna learn anything. And even worse, and this happens, I think, starts happening at a very young age in school, you seek the approval of the teacher or coach or whatever, as opposed to really doing that, delving into oneself.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, pleasing yourself. That's right. That's right. So, you know, the example you got of this person, which fortunately at most you only see once every 10 years.

Jeffrey Madoff: That was even seeming a little often to me, but yes.

Dan Sullivan: My sense is that he hasn't the foggiest idea who he is.

Jeffrey Madoff: How do you know when you know who you are?

Dan Sullivan: Your attention could be on other people.

Jeffrey Madoff: Interesting. And why is that?

Dan Sullivan: Because you're taken care of. One is I think you like yourself for one thing.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I do.

Dan Sullivan: And what I mean that you're not trying to be someone else. People are trying to be someone else. Don't like the one they have.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, because I don't think you're saying that with any sense of the person being arrogant. It's being anchored. Is that accurate?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, yeah. And I think those type of people you can organize your life around.

Jeffrey Madoff: How do you mean?

Dan Sullivan: ‘Cause they're going to be a sure bet.

Jeffrey Madoff: And what makes them a sure bet?

Dan Sullivan: Well, they're not trying to be somebody else.

Jeffrey Madoff: So you're saying there's a consistency, a consistency.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Enormous consistency there. Yeah. Of all the people that you've had in all your cast, you know, the person who knows who he is.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. Stanley.

Dan Sullivan: That's right. Stanley just knows who he is.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. And it's not coincidental. He's one of the older cast members. So he's had the life experience that he has learned from.

Dan Sullivan: But I could tell meeting him.

Jeffrey Madoff: You've met him a few times.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. I met him at the workshops and I met him in Chicago when you brought the cast straight out to the front lobby and he was there. But the role he plays is the stabilizing anchoring role for the entire production. Who Logan is when he's Logan is who Stanley is when he's Stanley.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, interesting. You say that because we're having lunch together in Chicago. I think it was, it was actually Malvert. It was actually Malvert. And he said, this is a character that reflects more of who I am. Said, I don't carry a gun or anything. He said that his sensibilities and his lack of bullshit, he said, I think of myself that way. And he sees more of himself in that character. That's, by the way, another interesting thing is I think what separates an actor, and this is also, again, true in business, is that early on in Chicago, early on, it was actually, we did a table read, and then we all, that was the first day, and then we all went out, we had a, we took over a bar afterwards, just so the cast could bond outside of the theater.

And I was talking to our young Lloyd, Darian Pierce, who is very talented, and so, and he's from Iowa. He said, you know, I'm having a problem with the character. And I said, what's that? And he said, you know, because it's so different from my life and I don't really know how to get my arms around who he is. And I said, tell me where you're from again. He said, I'm from Iowa. And I said, and where do you live now? He said, New York. I said, well, how come you moved from Iowa to New York? And he said, well, there was nothing there for me in Iowa. And I wanted to make a life for myself. So does that sound familiar to you? He looks at me and then the light bulb went off and he goes, yeah. And I said, so you two have very much in common, small town, too restrictive. You had more that you wanted to give and express of yourself. And you went out to that bigger world and took that chance. Yeah, you have a lot in common with this character. And he goes, man, I never thought of that way.

Dan Sullivan: And here's the thing that if Stanley didn't know who he was, he wouldn't be asking you the question. He'd be trying to hide from the possibility that you would say, you know, Stanley, I don't think you're quite grasping this character, but he's the one who brought it up because he's comfortable with who he is.

Jeffrey Madoff: This was Darian who played young Lloyd.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, I thought you were talking about Stanley.

Jeffrey Madoff: No, no. It was Darian talking about because Stanley honed in on it immediately. And it's interesting because I think a lot of it comes down to how do you find something in that character that resonates with who you are? Because, you know, the two-dimensional heroes and villains aren't very interesting characters. But if you can imbue that with something that actually anchors it to your emotional ecosystem, it becomes much more credible because you know how to become rather than act like, you know? And so I think that's a big part of it, which I think is quite fascinating.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Well, it's just something I mean, I develop, you know, my sense, I mean, I don't do the amount of auditioning that you've been through recently, but I've been auditioning people for different situations, different projects. And the first thing that I really check out is does this person actually know who they are? So that asking them to learn, asking them to adjust is not going to be a problem because they're grounded. They have an anchor for themselves. So I think I brought it up as a topic for our podcast today is that my thing is that I'm always sizing the person up. Does this person actually know who they are? Because if they know who they are, then they can go through a tremendous amount of learning, tremendous amount of change, because they always know who they are at the other side. And people who don't know who they are, it's very unpredictable how they're going to respond to challenges.

Jeffrey Madoff: So how do you determine, or what is your criteria, or what questions do you ask to determine if you think they know who they are?

Dan Sullivan: I ask them about their experiences. And a lot of people don't want to talk about their experiences.

Jeffrey Madoff: Like what kinds of experiences? How do you mean?

Dan Sullivan: Their learning experiences especially, and, you know, so, you know, you can just ask them a question. If you had to take your business experience so far, was there one project where you probably learned the most from that project? And I just ask how readily they can retrieve it and then how they can talk about it. And this is what happened, and this is what I learned from that, and everything else, and the manner in which they tell the story. How do you know when the character's just right for the role? But you have a sense that you kind of have a sense of who they're presenting themselves to be. And then you want to see if their own description of how they learned. Talking to people about how they transformed themselves is a really good story. Because if they talk about transforming themselves in terms of external results, rather than in terms of what they internally learned, the first person, they don't know who they are.

Jeffrey Madoff: And the external results you're talking about is they may say that.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I made this amount of money, then I did this and then we did this and everything like that. But the other person said, you know, and what I notice is that when people explain who they are, it's actually a simplification. They've taken a lot of experience and brought it down to just, you know, you gotta just get a handle on who I am and what I want and everything like that. I remember, I don't know if I told you this story, but I was divorced and bankrupt on the same day in 1978, August 15th. Yeah, I told you the story and I have this sort of joke. I said, you know, one of the neat things about when you go through an experience like that is that other people leave you alone. And they don't say, Dan, we're having a party. I'm having about 30 people over, and I wonder if you could just come over for the evening and just tell us about your divorce and bankruptcy. I said, they don't do that. They're very considerate.

Jeffrey Madoff: I wonder if you could come over and tell us about your divorce and bankruptcy. That would be an up.

Dan Sullivan: Some of my best friends. Some of my former wives. Anyway, so I had about a five-month period, so August, and I was going through that period and I was kind of like, I was very calm. One of the things I really noticed, I was very calm during that period. And I said, you know, I think the reason I got both of those results is like two bad report cards on the same day, um, is that I haven't been telling myself what I really wanted. And so I came up with a project and I did it and I said, I'm going to start journaling and every day I have to write at least one sentence. If it goes on for more, if I write a paragraph, maybe I write a full page. Don't go beyond a page. And I'm just going to do this for 25 years. And that started on the last day of 1978. And so that was December 31st, 1978. And on December 31st, 2003, I finished. And there's 9,131 days, and I missed 12.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, congratulations.

Dan Sullivan: And over that period, Coach got created. My relationship with Babs got created. And I'm a great wanter. And the big thing I learned about wanting, you never say because, you just say you want it. I actually wrote a book, we actually have a patent on the idea, called Wanting What You Want. You say, well, why do you want that? And then people start telling you a story about what they want. why they want something. But the truth is they want it because they want it. And then they tell it fiction. But that wanting really is a reflection of who you are. you know, doing that. So I had that experience, that 25-year experience, and everything changed. I mean, you know, every aspect of my life transformed just by my daily saying, yeah, and I want this, and I want this, and I want this, and I want this, and I want this. And it's one of the more powerful books that I've ever written. It's the first quarterly book that I wrote.

People said, well, there's always a because. And I said, well, the because is you want it. And I said, when you say because, you're trying to justify it to other people. It's like, why do you want a Broadway play? Because you want a Broadway play. That's the reason. Why do you want this play? Because I want this play. I want this play. The person who told me the story is so great. I just want this play. I just want this. And I think people are picking up on your resolution as we go forward. You know, you've told a quite a marvelous tale about that one week in London and everybody who's come into your life from that one week. And I think what they're doing is they're picking up on your absolute certainty that you want to do this. Well, that's, I think that gives you a great ability to just pick up on the people who really want the roles.

Jeffrey Madoff: Definitely. There is. Well, it's interesting. There are people that are, there's different categories of actors. And I'm talking about there are those that are offer only. They won't audition, they're offer only. They feel they're well enough established. Now some of those people are in fact well enough established and they don't want to audition if you want them. What I want is whoever comes on board in whatever department to be emotionally invested in the outcome that we are all seeking. And so you realize, just like the story I had told in the past about Sheldon picking up the vibe that that woman was going to be high maintenance, you know, in terms of someone who had that talent, but will not enough to justify putting up with the attention she would need on a daily basis. You know, it's interesting. It sounds to me like what you were talking about in terms of referencing yourself in the transformation that happened leads me to suspect that that's also when you learned who you were. And was that a result of self-reflection, feedback from Babs, a change in how you related to clients, all of the above. What was that?

Dan Sullivan: No, I think it was internal. Wasn't anybody's feedback. There were numerous situations that came up over those 25 years, as there would be, that somebody would suggest something, and where before I would try to accommodate them, you know, not a bad thing, but just going down this idea, and I could tell right off the bat that I didn't wanna do that, and I just don't wanna do that. And I think that wanting muscle, it was that muscle, I was exercising that muscle every day. I remember Kathy Kolbe gave me a brain test once. She was doing it for Arizona State University and the U.S. Army. And it was to detect when you're given a very, very difficult task, first of all, what happens to your brain that they can sense? They put sensors on your head. And the other thing is, how quickly can you resolve a solution to the issue?

And what it was, they had this bag. It was like a plastic bag. And it was filled with all sorts of objects that really didn't have anything to do with each other. There were rubber bands. There were nails. There were little balls. There were 50 different objects, and they didn't have any natural connection to each other. And so they gave you five minutes to sort out, to create two categories for the objects. And then they watch your frustration level because you're sitting there. I think their experience with most tests, people are, they're getting more and more frustrated. You know, they can feel their blood pressures going up. And this was all to determine if there is a brain difference between officers and people who should be following the orders of officers, whether they could solve it. So, I started in, I just started moving this, this, this, and at the end of a minute and five seconds, they gave me five minutes, a minute and five seconds, I had the two piles, and I didn't show any stress. So they got finished, and it wasn't satisfying to Kathy at all because she didn't get the result she was looking for.

The people with her, I'm not quite sure who they were, and she said, well, how did you create two categories? I said, I like these, I don't like those. No, I just pick it up, like it, don't like it, like it, don't like it, don't like it, don't like it. But the big thing is that a lot of people have a hard time knowing what they want and the reason is they don't know who they are. Okay. So they have to do a government commission to get an answer about who they are. But I think if you just are really clear that you like certain things and you don't like other things and you practice that on a continual basis, I think the person who emerges at the center is who you actually are when you're evaluating the talent.

I think you're evaluating the talent, but all the talent comes in at a very high level. But I think you're picking up something about the person themselves when you make your final, I mean all things being equal and the great story of the two possible Emmas, it was a talent problem and that's pretty easy to pick up. But I wonder if what's going on with you as you're doing this is that you're also picking up that inner resolve, that inner, not just ambitious and not just, you know, wanting a role and having the role, but there's just something about the person.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, it's interesting. You mentioned ambitious because I don't want to sense somebody's ambition. I want to sense their desire for the part. I want to sense of course their talent and ability to execute in those different areas that we need them to execute for that. But I don't want to feel their ambition, because their ambition has nothing to do with play. It has to do with them. And they have to be in the process of becoming that character. So it's how credible are they in being that character? Because I don't want this to be, and I'm sure this is true with most people, I don't want this to be just another gig. I have had the great fortune that every time we've done this, and it goes all the way back to the table read, people were into it, into the story and wanted to honor Lloyd's story.

Dan Sullivan: You wanted to be part of it.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right, that's right. And the thing that I didn't get to do in this go-around, and again, this is for a showcase, so it's not for the full-up production, ideally, but it just couldn't happen in time we wanted. I wanted to see how's the chemistry between the Emma character and the young Lloyd character, Emma character and adult Lloyd character, young Lloyd and older Lloyd. You know, because there's things that are very subtle. For instance, Edgar, the choreographer, will give, see if I can explain this right. Let's just say that Lloyd's got certain moves when he is the adult showman, and it's on a 1 to 10, it's 10. Well, young Lloyd should have that, but it should be like a six and a half or seven. So, you see the maturation of the talent. You know what I mean? So, it's really interesting what you look for. And again, how they can take the direction in order to do that. But, you know, not having the opportunity to put together the different combinations of people to see how they play off of each other, we'll be doing that in the rehearsals running up to this.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Well, just to sort of wrap up our podcast here, is that I think that who you are as Jeff Madoff for the last year in your eighth decade, and that being fairly constant, I think by this time you know you can really sense instantly whether you want somebody to play a role in your project or you don't. And you've given me lots of stories where you just sort of summed up the other person really quickly. I think the reason is that you're sensing something this person is going to have the characteristics that you admire when we go forward with the project. And that's part of casting. That's part of casting.

Jeffrey Madoff: You're right. And I think it's also, to put it back also into that entrepreneurial world, it's also a part of business building the ensemble of characters. You're going to help me take your business forward.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Anyway. This is a deep subject. You know, it's a very, how do we size each other up? You know, that's really, how do we do that? How do you know that someone's going to grow in the role?

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, you know, in terms of the casting, you know, that becomes a whole other thing. ‘Cause there's other things that play into it, you know, like the economics, you know, of it. I mean, if you're in business and you feel like you need a really, really smart marketer, but they're three times the cost you can ever afford in terms of what you're doing. Do you then settle for less? Do you try to figure out how to cut a deal with that person to do it, which you may not be able to do? Because they're also, most people are working on their own careers. So how do you strike that white balance where they see this is a potential great future advantage for them to having done this? You know, so, there are a lot of factors in there and wanting to recast a part to just get a different flavor of the play and see what that person brings into it. I mean, there's a lot of things and a lot of choices that have to be made. It's all alive.

So every part of it is alive. And I kind of love that about it. There is a scene—this is before we opened in Chicago where Sheldon made a suggestion about how about changing the power dynamic in this scene so that it is instead of Lloyd having to convince Logan, that Logan has to convince Lloyd and shift the power. I said, oh, I like that idea. That's a cool idea, man. And he said, you know, give it a try, you know, see what you think. And so I was so hyped up, excited about trying that, that I wrote it that night. And Sheldon was like, that was quick, but he really liked what I wrote. That was, you know, really he lit the fuse for it by giving me an idea that, oh, well, that's really cool. And it made me think in a whole different way about the characters, but it also enriched the characters. Because it wasn't Lloyd always finding the solution. You know, it was really interesting and it worked. And that's what makes a collaboration great, though, too. I think that if you don't want people to … I'm not willing to compromise on anything about the play, but I'm willing to make it better based on the ideas of others. Those others being a very small group like him, Sheldon.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, it's fascinating. There's a lot of mystery to this that, you know, it's not quantifiable. It's a particular quality. And I think our greatest capability is how we qualify things. Does it have quality or does it not have quality? This is what technology completely removes the qualitative assessment of a situation.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, that's right. Because, you know, robots, AI are very good at pattern recognition. They're very good at applying the same solution to a whole range of problems. And, you know, to me on a certain level, Remember the magic eight ball? Do you have one of those? That's a lot of like, if you clone yourself in AI, it's kind of like you made yourself into the magic eight ball. It's kind of like your horoscope. You can make up, you can think, wow, that really is like me.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, interesting the first time through.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes, yeah, and I don't have to do that again. That's right.

Dan Sullivan: Well, good. I got a lot out of this.

Jeffrey Madoff: What was your main takeaway, would you say?

Dan Sullivan: Well, I think it has something to do with wanting, that who you are is what you want. And I hadn't made the connection between that experience. And I think I needed my 25 years of self-work because I'm very open to other people's ideas and I can be very, very influenced. But a lot of the two situations that ended up in failure, success as I now see them, has a lot to do with just being aware of what other people wanted without something to bounce it off. And I think I needed 25 years of corrective behavior to get it right.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, and you know, my sense is, again, it's what you do, what we both do. It's trying to solve certain mysteries, you know, and looking for those clues, but ultimately the most effective way to implement that is the person being engaged in the process of discovery about themselves, about what they're working on, about who they are, and all of those things. And I think that it's certainly worth another podcast, getting into the whole idea of self-identity. Who are you? And what does that mean? I was in a pitch meeting with a photographer and I already had the video gig and then this guy was going to be doing the photography. He said to the client, you know, if you like Herb Ritz, I can shoot like Herb Ritz. If you want this to look like Horst, I can make it look like Horst. If you want this, then he named like five or six different photographers whose work he could emulate. Reproduce, mimic. And I couldn't help myself, which is often the case. I've gotten better at that. But, uh, I said to him, well, who are you? What's your style? Or don't you have one? You just emulate other people. They didn't know how to answer. And I thought, you know, this is a pretty crappy way to try to sell yourself. You know, say how you're like, the only advantage you have is you're a lot cheaper because you're actually not them. So you're a lot less expensive.

Dan Sullivan: That's what, that's what he should be imitating.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes. Yeah.

Dan Sullivan: Anyway, really fascinating. And it's such great news that you got the, those are two key roles that you've filled.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, it is.

Dan Sullivan: It was one thing to offer it to the other thing for it to be accepted.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. Yeah, that's right.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. I had a feeling with Cedric Neal that he was going to say yes. And I mentioned it at the time. I said, I think he'll do it. And you know, the reason was that I mentioned at the time, tell me he's from Texas. And it gives him a whole new dimension in London to be doing a role of somebody. I mean, it'd be interesting. I don't know where he is from Texas, but if he's from Southeast Texas, that's very close to New Orleans. And I just wonder what his background is. I didn't, I didn't really look it up, but I had a feeling that to play this character means something very, very important to him. And that's why he went for it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. And I want to discover what that is because I think you're right in the direction that his career is going. He's got to do something that's going to really showcase his range and talent. And I think that this is that part.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and it's a serious role.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes. You know, this is good. And I think there is a lot more to go there. I mean, it's really, really interesting. You know, the caterpillar in Alice in Wonderland, you know, who are you? Who are you? Do you know where you're going? Then it doesn't make any difference if you don't get there because you don't know where you're going. I've read that book like four times.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, it's so great.

Jeffrey Madoff: It's so brilliant. Thanks for joining us today on our show, Anything and Everything. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend. For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

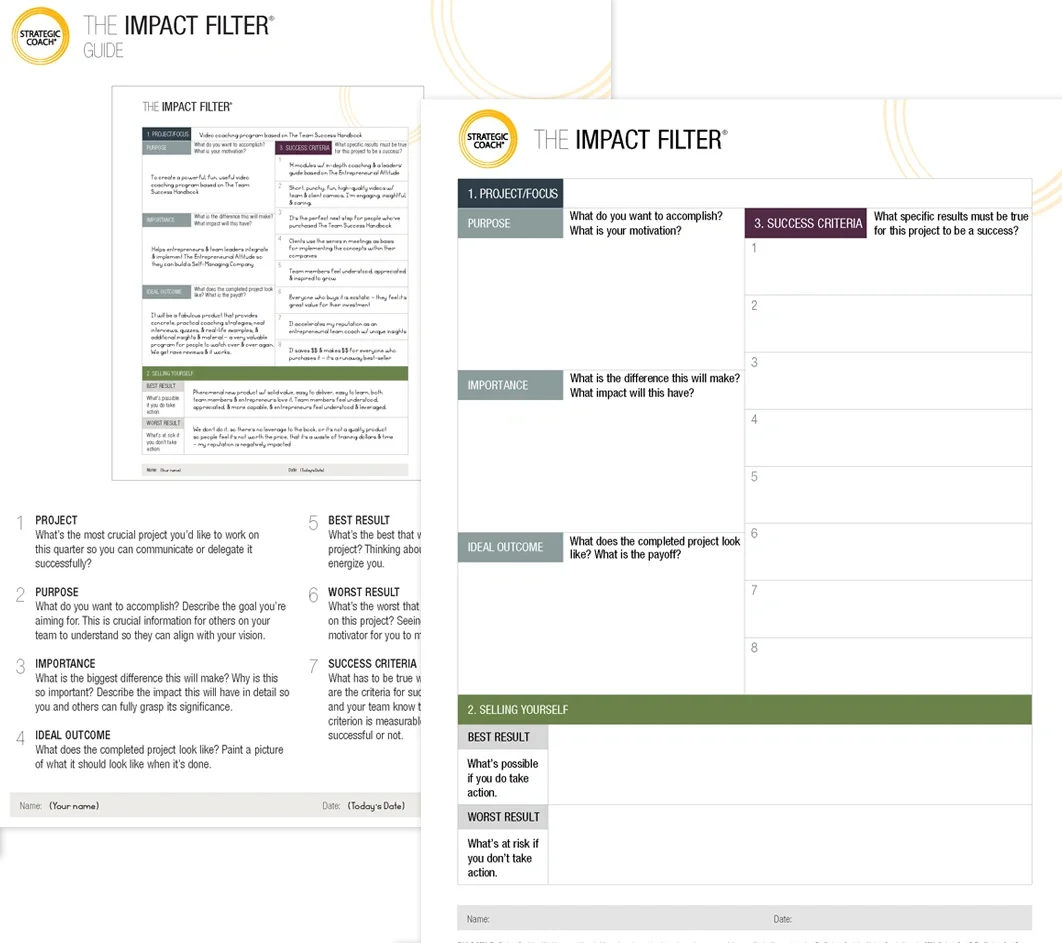

The Impact Filter®

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.