Why You Should Give Yourself Permission To Look Foolish

February 04, 2025

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

What is it about creative people that sets them apart? Why can some people consistently create new things while others can’t? Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff discuss the individuals who bring new value into the world and the best ways someone in business can use their creativity.

Show Notes:

- Quality is the foundation of every successful business plan.

- Never say no to yourself; there are plenty of others who will do that for you.

- Instead of wasting time pondering your ideas, you often just need to take action.

- No one has ever spent any time in the future or in the past. All we have is the present.

- Many people dismiss ideas prematurely without knowing how they might turn out.

- The majority of people struggle to engage directly with the marketplace.

- Creativity isn’t only about having a unique vision. It’s also about taking that vision and being able to replicate it.

- You can replicate a creation, but not its creator.

- To build a thriving business, focus on faithfully replicating what has been successful in the past.

- Every new creation has a limited lifespan; innovation is the key to longevity.

- Balancing creativity with consistency is crucial. Too much focus on expansion can dilute the original experience.

- Your customers are 50% of your creative team. Their feedback and insights matter.

- Beware of letting greed influence your creative process. Passion should come before profit.

Resources:

Personality: The Lloyd Price Musical

Your Business Is A Theater Production: Your Back Stage Shouldn’t Show On The Front Stage

Learn more about Jeffrey Madoff

Dan Sullivan and Strategic Coach®

Episode Transcript

Jeffrey Madoff: This is Jeffrey Madoff, and welcome to our podcast called Anything and Everything with my partner, Dan Sullivan.

Dan Sullivan: Jeff, we've talked a lot about this topic. You've written books about it. You have interviewed and interacted with thousands of people who are this way. And it's about creativity. And it's about people who create new things. And they're committed to doing this. They're very consistent about doing this. And the question is, why can some people do it and other people can't? That's my question. That's my question. What do you think about that? You've been around it, you're creative, you've got 50, 60 years of proof that other people can attest to. What is it about creative people that sets them apart and why can't everybody do it?

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, that's a huge question. I think that a lot of people disqualify themselves. And my belief is don't say no to yourself, because there's enough people that are gonna tell you no, don't do it this way, don't do it that way. Here's what will work and all that. And before we started recording, you were talking about how you're good at talking about the past, because you have a lot of experience having had a past, but you haven't really lived in the future all that much. You don't have as much to say.

Dan Sullivan: As far as I know, nobody's been there.

Jeffrey Madoff: When is the future? Is it now? No, is it now? Is it now? So I think that with creativity, a lot of time often is spent wasting time talking about whether something's feasible, when in some cases, you just try it. And you allow yourself to not be afraid to make an ass of yourself. You know, you put it out there, you try it. I was doing a shoot in Las Vegas with Victoria's Secret some years ago. We were at the Flamingo with all this amazing lights. And I said, I want a shot of the model. I want to do a silhouette of her body. And he said, well, you know, she's all backlit. And I said, I know that's why we'll get a silhouette. And he said, but the difference is such that it's not going to work. And I said, what do you mean it's not going to work? And he said, well, it's not going to work. Look at the scope. You know, the blacks are crushed. It's so dark. And I said, look at the picture, it's really cool. I don't care what the scope tells us, that it's not within spec, let's try it. And he goes, well, you know, you gotta be at least at whatever the number was, 8.5 on your black level, and black level's crushed down to, and I said, wait a minute.

We've now been talking about this for 10 or 15 minutes. I just want you to roll the camera, I don't wanna discuss it anymore. It'll either work or it won't. Everything else is hypothetical. Well, not only worked, it ended up being the lead on a national news station about this shoot. And it was really cool looking. And I learned an important lesson then because when you're trying something that the requirement to actually execute the idea is no big deal, it's not worth talking about. You try it and it works or it doesn't work and you move on. And I think to me that became a real example of creativity because so many people disqualify things from the get-go and they have no idea how it's gonna turn out. So why not try it and don't be afraid if it doesn't work, it didn't work. Otherwise it's all speculation.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, fortunately, I think for both of us, we had enough confidence and capability at a fairly early age. And I think you were in the marketplace sooner than I was. You were in your twenties. Mine was 30. I was 30 years old when I started, but I had done a lot of creative projects where there wasn't a marketplace payoff, but I'd tried a lot of different things. And mine was in the area of, now I know looking back, it was that I wanted to create a new kind of educational approach where the students use their own experience to create the lessons that they were learning. In other words, you break down your experience, what worked, what didn't work, and then you take what you learned that didn't work and you make adjustments and changes. And what did work, you double down on it and you create a new thing that consists both.

And then you try it out on paying customers. You know, do they write you a check for it or cash or credit card these days? But anyway, and it seemed to me that you were either going in that direction or you were following orders. And I checked out my ability to follow orders and it wasn't really good. So I said, I've got to just get really, really good at what I'm doing, find the target market for it and find out how I can do it consistently with new stuff that people will pay me for, you know, and that really, and I think a lot of people, and you're hitting the marketplace head on. And I think the vast majority of human beings can't hit the marketplace head on.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, as you know, that's part of what I go through with play. You know, do you sell tickets? Do people come to the show? Do they come back? You know, we have a very high percentage of people that came back a second time and brought people with them, that sort of thing. But what interests me, and this is not only like a play, it's also like Strategic Coach. So I wanna go to this place, which is creativity isn't only about having a unique vision. It's also about taking that vision and being able to have it replicated, you know? So there's one Dan Sullivan, actually, not if you Google your name, there's many, I hate to tell you that, but there's one Dan Sullivan who—I tell you, in Dublin, it's like John Smith. Yeah, so we're able to replicate the name, but not the person.

When you create the tools for Strategic Coach, in order for your business to be on sound footing and for you to be doing what you want to do, you've got to have a system where your work, your creative output, can be replicated. So it's totally faithful to what you're doing. If people sign up for Coach, they are, and this is not a testimonial for Coach, it's just you set up a creative business that facilitates your creativity and how that creativity is followed through after you create that tool. Your creativity is followed through by being able to replicate that and then create new tools because you also have the revenue that you can be creating new things as what you've done before is being implemented.

So it's not unlike a play. Play is written, rehearsed, you open up and you go. Nothing's changing in the script, but you've got to replicate that faithfully every performance to keep people coming to it. And that hit me when I was doing a post on LinkedIn recently about Hilary Sterling, who is the executive chef of Ci Siamo. She is getting a James Beard award this year. She's phenomenal in terms of the inventiveness of what she does.

Dan Sullivan: For our viewers and listeners, this is a great, great New York restaurant.

Jeffrey Madoff: And yes, this is the most fabulous restaurant in New York City. And what she has to do, she said, you have to realize I have to get this entire kitchen aligned to replicate not their vision, but my vision, that's what they have to do. So it's gotta be right every single time. As Heraclitus says, you can't put your foot in the same river twice. It always changes a little bit. But what you need to do is try to faithfully replicate what was successful, because that's of course how you build a business. So do you see any kind of a paradox between having to create something that is unique, but also something that is able to be replicated.

Dan Sullivan: No, the whole thing is that the new thing you've created has a lifespan. For example, I've seen people who got very famous, and I'll use restaurants as an example. And they were a big hit, but the menu didn't change at all over a period of time. So it was a hit in March, but in November, it was getting a little bit tired. There was nothing new about it. Then the skill of the back stage wasn't up to what people were expecting. So we have a chef here in Toronto, Susur Lee, greatest chef that Toronto has ever had. And he's about 70 now, but he's been doing this since he was 30, 35, where he had his own restaurant. And I remember when we first came across him, Babs and I, would have been ‘93, 1993.

So we saw him about a month ago. He's got a new restaurant, a new facility, new restaurant, and everything like that. And he did tasting menus. He was the chef who introduced tasting menu to Canada, to Toronto. And Charlie Trotter in Chicago was one of the pioneers for the tasting menu. You had a choice. You had a fish menu or you had a meat menu in those days. Now you have a vegetarian tasting menu, but it's seven or eight courses, and then you have dessert. And he did a different one every night, six nights a week. He had a brand new tasting menu, and the staff had to come in at two in the afternoon, and they had to taste everything. But now he didn't have any menus, so they had to describe everything that was in it. And they had to be really, really, really good.

What happened as more and more restaurants developed, he couldn't get the talent. But still now, after 35 years, if you go to his restaurant, there's always something new that he's trying out that night. Every night you go back, there's something new he's trying out. And he's just great. He just is always putting it together. And if you work for him, I mean, Ci Siamo is probably the same. If you have a record of having worked in the back stage, your future is almost guaranteed as long as you're not taking drugs too much.

Jeffrey Madoff: Too much. Yeah, well, so Hillary, when she is having them work on a new meal, you know, a new dish for the menu, and they have to learn it. And it's interesting, I think of the term, oh, you know, he has, she has really good taste. Well, just like there are in the fragrance world, there are people that have the noses, or they're paid a lot of money because they can discern six, seven layers of fragrance within a perfume or a cologne. And the same thing with food. The way that you are trained to taste things, and if you have the good taste, that you can do that. But where do you draw the line between, okay, I've created something new, and now it's going to be replicated? And how much of creativity do you think has to do with consistency?

Dan Sullivan: No, I think it's, I think it's huge. And then are you good enough that what you're doing new is consistently hitting, you know, hitting a particular, it has a lot to do with your customers too. I believe that your customers are 50% of the creative team, you know, and you, you have discerning chefs and you have, you know, you have top notch team and the restaurant front stage and back stage, but you also are drawing in people who love the experience that you're creating. It's not just the food, it's the entire presentation and how you're treated during the evening and you're not being told, well, you have to be finished with your table by a certain hour, you know, we've got more people coming through. The big thing is that how do you multiply without it seeming like scaling?

So draw the distinction there. I think scaling is where you reach a point where, I forget who was telling the story, it was some speaker at Joe Polish's Genius Network. And he was on the original Pixar team. He was on the, you know, the very first group of people in Pixar. And they spent one weekend, the first seven hits, they worked out on a weekend. You know, toy soldier and, you know, what was the name? I forget. I saw them all, but I don't necessarily remember them all. But they were all, they were all really superb. And he was telling us a story, not about Pixar, but he was telling us a story that Steve Jobs, because Steve Jobs was part of the origin of Pixar during his sabbatical from Apple, he got fired. And so he came back and there was this mom-and-pop sandwich shop that was close by the Pixar studios. And everybody going, and they just raved about the, you know, people stood in line to get the sandwiches. And anyway, and then they decided to have another part of the restaurant that was desserts. Okay. And they did that. And then they had another part of the restaurant that did this. And after a while, the sandwiches weren't very good. And the business failed.

But what was happening the weekend, you know, the weekend they got together to create the original Pixar and they had such a hit right off the bat. People say, hey, we can do this and we can do this and then we can put it into this form and we can get this. And he said, why don't we just make great sandwiches? Why don't we just be known for one thing? Why are you taking this and spreading it out? I think there's a kind of greed that comes into the creative process where you're really money motivated now. It's not about the experience you're creating. It's not about the special way you're thought about in the market. It's just surely about the amount of money that you can make. And I think that's, that's, are you multiplying so that more people can have the original experience or are you taking the original experience and commodifying it so that it can get out across? I can remember that Starbucks, after they had 700 stores, it started declining. I mean, go to Starbucks. There's far, far better coffee places to go than Starbucks now.

Jeffrey Madoff: I agree. I agree.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. I mean, it doesn't taste as good. I mean, it's, I think it crossed over when they couldn't get human baristas anymore and they automated the process.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. I mean, and what by the way, what an interesting thing. Did we know what baristas were until we were in our, you know, fifties or something?

Dan Sullivan: We were Americans. Why would American know what a barista is?

Jeffrey Madoff: And that became like an occupation. You know, became a thing that's in demand because where I live in New York City, you can't walk three blocks without going by a coffee, two blocks without going by a coffee place. You know, it's highly, highly competitive. I mean, the margin has gotta be crazy. It's probably, you know, each cup of coffee probably, including the cup, probably costs them four and a half cents and you're paying six bucks for it. You know, the ingredients aren't much. But I like that distinction that you drew between are you trying to make a unique experience or are you commoditizing? You know, and sometimes you're trying to do both.

Dan Sullivan: What I would say is that I think there's a limit, there's a zone where you can get away with it, but you take one further step and the experience disappears.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right. So Michael Arndt did my class. He won the Academy Award. He won two Academy Awards, one for Toy Story 3 and for Best Adaptation and for Little Miss Sunshine for Best Original Screenplay, which was a wonderful film. And so I said, so what, you know, consistently Pixar has done great work. And I remember the beginning of the movie Up, you know, eight minutes. And it was without a word.

Dan Sullivan: You're crying after eight minutes.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. Just fabulous, fabulous, fabulous film. And I said to Michael, so what is it that's unique about Pixar? And I was reminded when you said that, you know, can't we just make sandwiches? Pixar is first and foremost story. That's the most important thing is story, period. It's, you know, it's a given that you can make the animation look good and, you know, all these other things, but what it takes is a great story. And that's what they do. So he said, you know, what would happen in these story meetings is that they would come at it from all different directions, poke holes in it, whatever, because they wanted to make, they knew that what separated them from all the other animation studios out there was its ability to tell a great story. And they haven't shied away from that. That's what they have continued to do. So they've never commoditized themselves and they don't put out a ton of films either. Relatively speaking, it takes a long time to put together an animated feature. And the other part of this story is that, and I love this and I have to credit Michael for saying this, because I think it's terrific. He said, the belief is, and he said, and this is my belief, and I share in it too. Quality is the best business plan. You create quality because yeah, you can pump up mediocrity and you can sell it cheaply and you'll have a market.

Dan Sullivan: We have proof.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right, lots of it, lots of it. But if you really wanna feel a part of something as the creator of it or a co-creator or someone who helps the process move forward, quality is the best business plan is really fascinating. And I saw that with Ralph Lauren. On one hand, Ralph never got the credit he thought he should get for being an innovative designer. And that would always go to the Italian and French designers. And that was often the bane to him that he wasn't recognized for that. But his business now is more profitable than ever. And it's because he is consistently stuck to what he believed in. Never tried to second guess the consumers. And he was a great example. I worked with him for over 35 years. He was a client. Quality is the best business plan. And I think that that's really true. But do you get into anything—how can I say this? When you are dependent on other people to replicate what it is you do, to reach that market that you want to reach, how do you protect the creativity and not become commoditized, which is the temptation because you're buying more and the business is growing and all of that. How do you protect the creativity so you're delivering that quality product all the time? And you've got to face that in terms of what you do.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And one is, so we're, you know, just coming up exactly on 35 years since we started doing the workshops for entrepreneurs. So we started in 1989. And one of the things that I saw immediately, because I was early in the marketplace for being an entrepreneurial coach. And so, you know, one of the toughest sales since 1974 is when we started. And first of all, you had to explain what a coach was, you know, because coaching people knew it from sports and they knew it from areas of art, you know, dance, you know, there were, there were coaches, but it was a bureaucratic, it was a corporate bureaucratic world in the 1970s. And entrepreneurs were marginal creatures, you know, but what I worked out really quickly and that it was 15 years of individual coaching before we made the jump to the workshops.

And the big thing I said, you have to make a decision whether this is going to be based on personality or it's going to be based on a process. And so I said, I can't see any. First of all, I don't have the personality that I would want to grow in the marketplace. I don't want it to be about my, you know, who I am as a person. I didn't want it to be, you know, and but you could have a question-based process where you could structure a learning experience where the entrepreneurs are using their own experience and they're answering questions on a sheet of paper and there's a progression of questions that you could watch in the room and all of a sudden people say, whoa. Whoa, you could just see that they had put enough of their answers together that they were getting a new insight. So that was the creative process in what we were doing.

And, you know, and we've had enough other people try to steal our stuff, and we've had enough people try to duplicate what we're doing to know that it's the way we do it is fairly unique. It's hard to reproduce. And that was just thousands and thousands of hours of going back and forth with one-on-one customers to the point where I said, I can do this with a whole room. You can do that. And so far, we've got one person in the company who is at about 80% where she can do it. And she's worked with me for 26 years. And she's starting to get it. And I said, you know, she asked me, you know, what's the trick here? And I said, you have to start with the punchline. And the punchline is? Well, it's that aha moment that people are going to get. Okay, so you have to be inside the entrepreneur's brain and you have to say, oh, I just saw.

And it's a simplification. They have a lot of complexity. And all of a sudden they get a tremendous simplification out of their thinking. But it's all their experience. I don't know what they're writing down on the sheet of paper, but I know the thought process that they're going through. But the one thing is, I can put it in such a way that everybody can learn the questions and everybody can learn the process. Okay. And these are our coaches. So we have our coaches. We have 17 right now. And I can see us right now that we could double that number without any loss of quality. So I don't think we can have, we've got 17. I don't think we can have 1700. And it goes beyond it that they all have to be in my workshops as entrepreneurial clients. So I have to have personal contact. If they can't be with me in my workshops, I think the quality is gonna be lost.

Jeffrey Madoff: So an interesting thing that comes with that is right now you have 17 coaches. I have actually 17 actors, 18 actors in my play.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I think the upper limit's 17. I don't think you can get beyond 17. 17's the number, yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: And so my question is, you know, and we've just been through this, where we recast for the Chicago showcases we did. Everybody brings something to what they do. So my, the compass for the play is you gotta do the words that are in the script. But one person might say something that gets a laugh with a certain line, which is great. Other times, if the laugh really shouldn't be following that line, something's the matter, you know.

Dan Sullivan: There shouldn't be a laugh.

Jeffrey Madoff: There should be a laugh, but sometimes not at that point. We've all sat in on movies where something happens and people laugh, and I'm thinking, why are they laughing? That's not funny. But I think some people are just uncomfortable and laugh as a result. But anyhow, so you've got your 17, let's call them actors, because they're front stage when they're coaching. How do you monitor, or monitor isn't the right word, but how do you make sure that they stay within the guardrails and are faithful to what it is you want to do as they feel they've gotten stronger in the part and feel like actually, I've got something to add in this, and maybe it's good and maybe it isn't, but how do you protect the Strategic Coach brand to make sure that everything that is done is within those parameters of Strategic Coach? Because I think a lot of businesses have that problem.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, the other decision I made before we had any coaches was that we had to have a team between me and the coaches that knew the material, you know, they really knew the material. Like theater, we have an audition process for the coaches, and we really throw a tough room at the prospective coaches. They have to perform for about two hours in front of 15 of our team members who are acting as difficult clients. So there's a bit of a gauntlet that they have to go through. And we want to see, do they find that an enjoyable experience being presented with unpredictable audience response? And you can't learn that. You're either comfortable with it or you're not comfortable with it. And the other thing is, I don't want them to have my speaking style. I don't want them to have my mannerisms. I don't want them to have my timing or anything else. They have to develop that on their own. So they have a framework in which they can create their presentation. But, you know, we have numbers to indicate whether they're doing a good job. And our numbers are, you know, we get them in for the first year of their workshop and it's a room. How many of them come back for the second year? How many of them? The one is how many do you get in the fourth year? And if you get half of your first year into your fourth year, you're a very profitable company.

Jeffrey Madoff: Mm hmm.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. So the big thing is, and I'm open to innovation with my stuff. I mean, if they can come up with a better way, they have a better story in that. We just build it in. So we have a process where we, we build it in. But my whole thing is the quality of the experience that the clients are having, you know, and so I'm fairly comfortable. I mean, we own the property and we've been good on, you know, intellectual property, making sure that our name is on it and everything. And we've sued once where we had to make an intervention in someone's use of our material. But it's tough stuff. I'll relate it back to personality in the play. I don't think you could steal that play. There's just too much nuance in it. There's just too much background. There's just too much relationship that's built that play. I just don't think you could copy it and produce it unless that was your intention, you know, that somebody, I mean, I can see Personality as a roadshow where you have five or six Personality. It lends itself very well to that. And you've proven that the talent is out there to do it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes. That's right.

Dan Sullivan: But the director won't be that. I mean, the director will be a director, but he won't be the director. He won't be the choreographer did it. They won't be the choreographer. But you'll have to fill those roles.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, they'll have to be faithful to what was done.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. You got to be faithful. Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. And the choreographer and the musical director and the director, you know, receives royalties.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, because they created part of them.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. Well, what is it that I can speak to it as an actor talking about an actor? What is it that in your world, the coach, brings, what do they bring to the process that works or enhances it? Because I also know you don't want exact replication. And you are dealing with a business that's relationships.

Dan Sullivan: Well, what's on the paper doesn't change. I mean, these are 8.5 x 11 forms. And there's a step-by-step process of how you fill out the form that you can't do it differently. You have to do it. You have to do it that way, you know, and it's been tested. I mean, you know, it's been tested a lot. I'm the, I'm the great tester of new product. And I do it, I'm an entrepreneur, and I said, does this, quite apart from being the creator of the material, as an entrepreneur who's got an entrepreneurial company, does this thinking in this thinking tool, does it do the job for me? So I've tested on that. And then I have shorter sessions, which are on Zoom.

Fortunately, Zoom's been great for this, where you can just test out a new, I can create it yesterday afternoon, I can present it this morning, and tomorrow I'm adjusting it in terms of the timing, you know, and my team sees it and they, you know, they say, that's a really good one. I think we should really go with that one and everything else. So I will tell you, it's hard to answer the question because it's been a 35 year process in the making. And so there's a lot of things that we do sort of automatically that probably someone looking from the outside would say, hey, wow, that was quite a step that you had there. But for us, it's just part of the step. You know, I mean, it would be like going through your showcase in London several weeks ago and remembering what it was like when it was just at the reading stage.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. And that brings me to what I find a really interesting thought, which is I believe that creativity is a paradox. At the same time that you want to do something that is new, that is original, I read this quote, and it's, the attribution is unknown in terms of who said it, which also adds to the interest of what the quote is, which is, originality is knowing how to hide your sources. And I just think that's terrific. Because there's roots of it somewhere else, you know, and everything that's out there.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. I mean, Shakespeare is a great example. I mean, the world's certainly most famous playwright. And, you know, in terms of the volume of work, the greatest playwright. And every one of his stories came from somewhere else. He didn't come up with the stories. There were these stories. I mean, he was just at the crossover from oral society to a written society. I mean, he was right on the move over. I mean, people memorized hundreds of stories back in those days. People knew the Bible by heart, you know, they could read the Bible by heart. Now, his was the crossover where you didn't have to do all that remembering, but, you know, you would be in pubs, he would be in settings where stories would be told.

So, stories were a currency, you know. And I think stories have always been the currency of entertainment. So the thing is, if the story works, there's no need to fool around with it. But I will tell you this, I don't think as many great stories as are out there, you know, and we have them, there's always room for more. There's always room for more stories. And a great story is a great story, you know. It either gets you or it doesn't get you, you know, but I think you put your finger on it, right? Thing is, I think creativity, if it's not a story, is it's probably not great creativity.

Jeffrey Madoff: But do you see creativity as a paradox, that it's both something that you're trying to be original, but you also want it to be replicated?

Dan Sullivan: I do know that it's a paradox that once you get to the bottom of it, you make a lot of money. It just goes back to our original question that started the paradox, why are some people creative? And one of the things I've noticed is a lot of people just aren't very good at stories. They just aren't very good stories. And, you know, they don't set it up properly. They don't create a context that people can really grasp what's going on. You know, and probably comedians are the greatest storytellers because they set you up where everybody's bought into an ending that suddenly isn't the ending and everybody goes crazy. But great drama has that, too. Not just comedy, but great drama. Those are the two forms, so it's either comedy or it's tragedy, it's drama.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, it's interesting when you mention that the comedy and then they pull the rug out from under you. That's what Rod Serling and Twilight Zone were so good at. And it wasn't comedy, but it was a complete change in the expectations one had, you know, which were brilliant.

Dan Sullivan: There was that one Serling, you know, the show that I saw, where it starts off with somebody's lawnmower not working, and then somebody's complaining that their car won't start. And then all of a sudden, it starts getting out of hand and around the community that they're living in, this is not moving, the lights won't work, and everything. And people start inventing stories while this is happening, and it ends up in bloodshed, it ends up in a riot, you know, one part of the community declaring war on the other, and at the very end, the camera comes right up to a hill, and there's two aliens saying, see, all you do is turn the power off with one of them, and the same thing happens every time they go to war. You know, but it's like a joke, you know, you bought in, you know, what's the resolution to this? And then you realize that aliens have set up this whole situation. And one of them's just saying, this is what humans do when the lawnmower doesn't work.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. I remember that there was one of the classic Twilight Zones is that you see the point of view of a woman who was a patient in the hospital. I'm sorry, the doctor's looking at the woman who is in the hospital and she's all bandaged and you never see the doctors or the nurses. And you know which one I'm talking about? It's called “In the Eye of the Beholder.” And towards the end, you just see the doctors from the back and they're cutting off the gauze and taking off the bandage and they're horrified when they see. And we see this beautiful woman and then from her point of view, you see all the distorted people that are the doctors and nurses. It's in the eye of the beholder.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, yeah. I mean, it's got everything. It's got suspense. It's, and I mean, it's occurring to you watching the TV that why aren't we seeing any of the doctors? Why are we just seeing the patient, you know, and everything else? So he really knew how to build suspense.

Jeffrey Madoff: Brilliant. It was brilliant. And the other thing, and this is a subject for another podcast, I think, but what's interesting to me also about the replication is, you may never see the Mona Lisa in person. But you can see it in books, on posters, and, you know, all kinds of other places where that creativity, not the creativity hasn't been replicated, the results of the creativity have been replicated. And, you know, when you're talking about the storytelling, well, first there were the scribes and then eventually with Gutenberg and the printing press, you didn't have to remember the stories anymore because you had a book and you could read those stories. You know, there were records. So the music had a recorded history. And so how those things affect our perceptions of what creativity is and what that is, you know, sheet music. I mean, on and on. I think it's really interesting because there's so many iterations of a creative product, if you will, and that creates other products that aren't really creative. They're more commoditized, if you will. But it also exposes more people to things they might not be exposed to otherwise.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, my sense is that, you know, in terms of how talent is distributed, you know, I think there's a bell curve for every capability. You have some at this end that just have it in spades, and you have somebody at the other end is just totally deficient, and then it's spread out on a bell curve. And my sense is that since all human skills are required for society to work, you don't need an overabundance of any one skill, but the ones that are really special, that are emotionally appreciated most, these are not equally distributed. And so it's like entrepreneurism, you know, everybody goes gaga about entrepreneurism. And, you know, I get interviewed and they said, do you see the world becoming more entrepreneurial? And I said, well, the statistics would say no.

And if you looked at the IRS, the Internal Revenue Service in 1974, when I started, that you could work out some numbers which indicate that this person gets paid for entrepreneurial activity. In other words, they don't have a standard tax form, you know, and everything else. And it was 5% of the adult working population in 1974, and last year it was 5%. Much bigger population. So it seems like there's a lot more of them, but proportionately not. And the reason is because no more than 5% are actually needed. If more than 5% were needed, we'd have them. But, you know, we've got enough of this skill. And the other thing is, as society becomes more complex, it creates new things that people can be good at that other people will pay you for, you know. But I think the U.S. is best at creating, allowing people to create new situations where they can create a new skill and be appreciated for it. And that's indicated by the fact that you can get paid for it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, the internet has opened up the floodgates to that, whether you're talking about an influencer and just like print publications did, you basically sell part of your time to those who want to promote through you because they think you influence consumers.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, one of the things I've always been struck by is the crossover from engraving to photography, that when you got to the middle of the 1800s, just before photography started to even be available, you had some phenomenal engravers. It was almost lifelike. But by 1900, they had disappeared. And the reason being photography. Well, photography had replaced the value that people got out of the engraving. You know, it was just like that. And they say, well, you know, we're going downhill. And I said, we're going downhill. You have to look at it from the standpoint of the person who wanted the representation. So, you know, if you could get it with photographs, you know, you didn't need the engravers anymore to do that. First of all, they were expensive and photography was cheap. You know, I was looking at what Apple can now do from a camera standpoint, you know, I mean, you know, I mean, you couldn't have done this with a camera 25, 50, unless you were really dedicated to the craft, you couldn't do what those, those can, you can change, you can change it from black and white to color. You can, you know, you can, you can do this, you know, everything else, but great photography, when we talk about great photography, it's not people taking pictures today.

It's like Ansel Adams, and it's like Margaret Burke White. We've got three or four Margaret Burke White photos from the 1940s. One is from the garment district, and she's looking down from the building, and everybody's got a hat, a fedora, and a floater. Actually, what do they call those? They're sort of the round, I think they were called floaters. And everybody's wearing them except one person, and she's picked up. And your eye immediately goes to the one person who … Sure. She's got one, and she's looking out at DC-6 at, you know, she's kind of looking at, you know, sort of Fifth Avenue. And from thousands and thousands of feet, you can pick up every individual on the sidewalk. You know, you can pick up every one of them. But great art, not just the camera. And she did a lot of that was really done in the editing room, you know, it was done in the darkroom. People still don't know how Ansel Adams got his sharp distinctions, and he never told anybody. He hid his sources.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. I love that. Can I just write it today, actually?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I think it's a thought worth pursuing is, first of all, I don't think people can actually explain how they do what they, I mean, if they're really great at what they're doing, they can't really explain how they do what they do. It's a feel, you know, it's a feel. And my sense is they shouldn't dig too deeply if it's gonna screw up their art, if it's gonna screw up their skill. Don't go too deeply, you know, with it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, there's the story about Sigmund Freud, who was the one who was getting headaches. And the more they dug into her past, kind of the darker it got. And he said to her, I'm paraphrasing, but basically, keep your headaches. You know, sometimes you're happier not knowing.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Yeah. Well, first of all, happiness is an activity, you know, do the things that make you happy, you know? And also, I believe all that is fiction anyway. All of which is fiction. Psychoanalysis. I think it's fiction. You're making up stories.

Jeffrey Madoff: Or I guess you could say, I would say if you're a really good psychoanalyst, you're recognizing stories and patterns. And you'll dislike me for this, but I think you're a good psychoanalyst. You ask questions, you don't tell any of these people what to do, you're not, you don't go to Dan for the magic, you go to Dan for the work it takes to do great things.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I think we make up our past equally as well as we make up our future. Yeah, we take this and this and put it together, you know, and people say, well, you know, you can't change the past. I said, you're doing it every day. Tell the same story to 10 different people. And I will tell you, it's not the same story.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. It's not the same story.

Dan Sullivan: You've judged their receptiveness to your story and you change this and you change that and everything else. Great defense lawyers know this.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. And we're always, I think, trying to make sense of where we are and what's going on in the world and what it means to us and all of that kind of thing. I think we're constantly trying to make sense of that. And because somehow in man's quest for meaning, humankind's quest for meaning, you're trying to figure out why this happened, is there, you know, and we don't really know.

Dan Sullivan: Well, I think we know to our satisfaction, in other words, that, you know, I mean, we have two Ohio stories to tell, and there's absolutely nothing in common with the two Ohio stories except Ohio, you know, in the 1940s. But I notice, you know, that I think a lot about my childhood on the farm. And, you know, and I'm constantly pulling new meaning out of, you know, something that happened 70 years ago, constantly. I hadn't seen that before. That's really, really interesting. Well, I'm not changing the events. I'm just changing my interpretation of the events.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. And a story is and follows a certain pattern. And so we all, we either create our own narrative or we feel victimized by living a narrative that others have put out there for us.

Dan Sullivan: And I think that you've just drawn the borderline between creativity and non-creativity. Yeah, well … I think creative people create their own narratives on a continual basis.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Dan Sullivan: I mean, it's very, very interesting, this story that you have to tell now of five very, very significant growth stages for Personality. You know, well, six if you include the original interview with Lloyd Price, you know. And when you get to number two, you see one differently. When you get to number six, you see the first five differently, you know?

Jeffrey Madoff: And yeah. That's why I always loved Heraclitus' statement about you can't put your foot in the same river twice. And that's why I also think people's recipes for success, people who have made fortunes, writing books about how to be successful. And it's basically based on, you know, like the millionaire next door or whatever.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I can just see the two Greeks on the other side of the river saying, what's he doing? Every day we come here, he comes in and he sticks his foot in and everything. What's his name? Heraclitus. Weird, what's he doing there?

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, because there are probably the majority of people that when he uttered that phrase, they didn't know what the hell he was talking about.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, yeah. Well, I got a lot of that. I mean, first of all, a good paradox is timeless. So, you know, we didn't run out of things to say about this. But I think as what you're bringing up here, this collision between replication and originality, I think really great artists learn how to deal with this. You know, a great, great creative people learn how to deal with this. And there are two tensions, but I don't think that it's ever a hundred percent one. You're always operating with two things in mind. You know, is this new and, you know, new and valuable on the one hand, that's the originality. And the other one is, can anyone else do this? And I think both of them are a great pleasure.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, yeah. And I think realizing that that phrase that we both like, which is originality is knowing how to hide your sources—whether we know it or not, we are influenced by what we see, what we read, what we hear, what we observe as we walk around, whatever. And that forms the tapestry of our thoughts, which can motivate a series of actions that can be creative. And the most important thing I would say is, don't say no to yourself if there's something that you feel you want to do, that you feel strongly about creatively. And it was, by the way, Hilary Sterling again, who said, don't be afraid to make an ass of yourself. Well, I guess that brings us to the end of Anything and Everything. And I think we stayed within the framework.

Dan Sullivan: We stayed with it.

Jeffrey Madoff: So thank you to Dan Sullivan. I'm Jeff Madoff. See you next time. Thanks for joining us today on our show, Anything and Everything. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend. For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

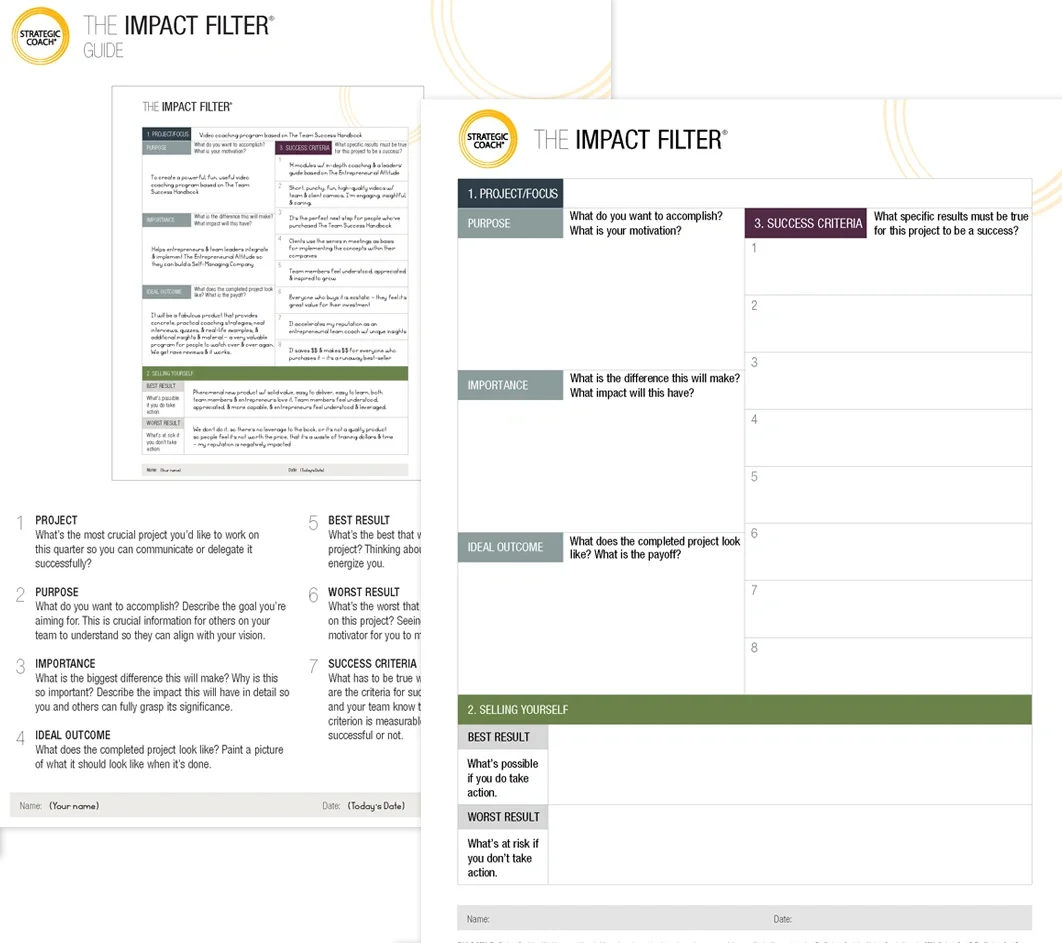

The Impact Filter®

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.