Being Weird Is Actually Wonderful

February 18, 2025

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

Do you see yourself as normal, or do you embrace your weirdness? Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff explore the nature of normality and weirdness, reflecting on their personal experiences. They discuss the importance of self-consistency, the impact of external perceptions, and how curiosity fuels personal growth and authenticity.

Show Notes:

Most people consider themselves normal and view anyone who perceives them as weird as weird in turn.

You don’t have to take it personally if someone calls you weird.

As an entrepreneur, you’ll likely find that other entrepreneurs share your understanding of what’s considered normal, more so than those outside your field.

You can remain true to yourself across a variety of activities and experiences.

Some people view significant life events as opportunities to reinvent themselves.

If you’re consistent, people who reinvent themselves might mystify you.

Reinventing oneself often involves distancing from people from the past.

A good story is better than a good statistic.

If what you’re doing works for you, that’s a solid reason to remain consistent in your approach.

A person behaving inconsistently might be trying to please others rather than please themselves.

Resources:

Your Business Is A Theater Production: Your Back Stage Shouldn’t Show On The Front Stage

Learn more about Jeffrey Madoff

Dan Sullivan and Strategic Coach®

Episode Transcript

Jeffrey Madoff: This is Jeffrey Madoff, and welcome to our podcast called Anything and Everything with my partner, Dan Sullivan.

Dan Sullivan: Jeff, I've sort of given the punchline of our theme today, but one of the things I came to grips with fairly early in my life in Ohio, as you are also from Ohio in the 1940s, is that I was different. I could tell at a fairly young age that I was different in the sense that I didn't do the things that my brothers and sister did, and I didn't do the things that … Once I got to school, I was noticing what the other children in my classes were doing, and I got little tidbits of comments coming back that Dan's a bit weird. You know, Dan's different, Dan's weird. And I grappled with that, you know, I grappled with it, you know, maybe all the way through school from 1 to 12. But at a certain point I said, you know, this can't go on for the rest of my life. I've gotta reach an agreement of how I'm going to think about this.

And the way I thought about it, and it's been going for 60 years now, and that is that I'm actually normal and that those who don't share in my normality are weird. I'm not weird, they're weird. And I found it's been constant, but it makes me interested in why other people are weird, you know, rather than comparing myself to them, but just seeing that, why do they think this way? And I just wondered, because we sort of hit it off immediately when we first met, and what I sensed was that there was kind of a joint normal way of approaching things that I sensed in you, which really resonated with how I looked at things too. So there you go, eat that elephant and when we go.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think that was a pretty weird story you just told.

Dan Sullivan: “I didn't know that about you, Dan.”

Jeffrey Madoff: I guess what I need is some definitions. So how do you define weird?

Dan Sullivan: Well, I'll start with how I define normal, you know.

Jeffrey Madoff: It's weird you just did that. I asked you one question. It was weird.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and the sense is that I feel a constant sort of experience of being me. In other words, like I can relate very, very easily to who I was walking around on the farm when I was eight years old. You know, I'm 80 now, so it's a good time span to establish some measurement. And what I mean by that is I don't experience myself being any different from the eight-year-old, except that there's an enormous amount more experience and there's a corresponding greater capabilities to deal with the world that I have now that I didn't have then. But I see a constant experience. I don't see any difference in the person, and yet when I go to places where we're talking to other entrepreneurs, well, I'm really a radically different person now than I was there. And I take them at their word that they have a sense that they're not the person they were. And it's not happened just once for them, but it's happened four or five times. There's kind of like new them that they experience. But I don't experience that. I experience a consistency and a sense of consciousness about who I am that is basically no different from 70 plus years ago. You've told enough stories about yourself that I sense that that's kind of what your experience of yourself is.

Jeffrey Madoff: There's actually a lot to unpack there.

Dan Sullivan: And that's normal. So that's my normal.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's your normal. Well, you know, I don't know. I don't think I've ever heard anybody say about themselves, yeah, I'm weird. You know, I think that most people feel that they're normal, but then when they find somebody who is out of sync with that perception, they're the one that's weird. I don't think that I ever thought of myself, I never thought of myself as weird. And I never thought of myself as normal. I just thought of myself for who I am, and I didn't really traffic in labeling myself that way. Because people that thought I was weird, and if that was supposed to be an offensive remark, you're weird. I always thought, no, actually you are for thinking that's weird. But it's kind of aligned with what your definition was, is if it's dissonant with what I consider to be normal, it's weird.

Dan Sullivan: It's kind of interesting. The thing that I found strange about them is that they wouldn't see a consistency to their you know, who they were over long periods of time, over decades, that they see themselves as somewhat significantly different as a person. Okay. And that's what I found kind of weird, because I have no experience of seeing myself earlier as a different person than I am now. You know, the experience is the same. I mean, I would hear comments that you're kind of weird, the way Dan looks at things is kind of weird and everything like that. I didn't really take it personally. They were just seeing something and they were describing what they were seeing. But the biggest thing I noticed, the difference between my experience and a lot of, and I would say this, that people who are entrepreneurial and people who are creative, share my sense of what's normal more than people who are not that way, people who don't make their living in a creative way. They see real differences in their life, and it has to do with their educational experience, their family experience, their workplace experience, that when they go from this to this, it's like they're a different person, you know? And I said, I have no experience of that.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, so I think that something quite possibly you and I share is that consistency of who we are. And if you met people that knew me when I was a kid, well, you have actually. In Chicago, you met my dear friend Ellis, since third grade. And so I think that there's a consistency. And I guess the inconsistency, one could consider weird. But then again, I guess there's other people who think consistency is weird. But I do believe that, as Popeye the sailor man says, I am what I am, and that's all that I am. And I don't feel, I mean, I've matured. I've done the things that you hope people—suffering succotash. So I think that part of what we're talking about is, especially with entrepreneurs, we both know entrepreneurs that have, to use the term, reinvented themselves.

I've done different things. I've never reinvented myself. I've been the same, whether I was designing clothes, whether I was running a film production company, doing a play, or writing a book, I bring all of that to bear with what I do. And I'm the same person doing that. And, you know, the people that reinvent themselves kind of mystify me. I mean, I had, there were some people, not many, but a couple people growing up, for instance, that I think they saw going away to college was a chance to reinvent themselves. Or if they moved somewhere else and embarked on a career, it was a way to reinvent themselves. And the interesting thing is what went along with that is that they cut off people from their past because they knew them and they didn't want anybody.

Dan Sullivan: I remember there was this person I met. He was a life insurance manager. He had a successful and we weren't friends. He was just someone I knew. And I knew him for about a year. And then I ran into someone who knew him, you know, from a decade ago. And he was sort of ambivalent. He wasn't saying, yeah, well, I knew him and everything. He was diplomatic, let's say, in his description of how we knew him a year ago. And then we had a third friend. I had a great friend with him who knew the life insurance manager. And I said, you know, I ran into an old friend of John. I won't say his last name, but John. And he said, that's impossible. John doesn't have any old friends. I bet you've run into people who don't have any old friends.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, I'm sure I have. Yeah. I'm sure I have. But, you know, I'm not looking for accuracy.

Dan Sullivan: I am looking for entertainment.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, I always thought that was weird about you. We're always looking for that. A good story is better than a good statistic.

Dan Sullivan: Yes.

Jeffrey Madoff: But it's really interesting because I also think it has to do with liking yourself. And I think there are a lot of people that are brought up, and it can be by parents, it can be teachers, it can be peers where you want to fit in, and that if you are brought up with what you do is not good enough, that you get berated and ashamed and those kinds of things, which happen pretty early in life to people, those who want to just please others. And I think that so much of that consistency, I mean, if what you're doing works for you, that's a good reason to be consistent in it. And if it doesn't work, and you want to try to win somebody over, that necessitates a certain kind of inconsistency. Other than the consistent part of inconsistency is you're always trying to please others. And so you'll do what you have to do to do that.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Well, you've just introduced a factor that I think is a determinant of whether you experience your life consistently over, well, throughout the entire lifetime, let's say. Or if you have this sense of different use, and it has to do with whether you're getting your information from the outside or from the inside. And what defines you? And I think I'm just putting this out as a visual model. I think there's a fork in the road fairly young in life where you make a decision definitively that who I am is going to be based on my own internal judgment. It's not going to be based on other people's judgment of me.

Jeffrey Madoff: I could see an adult making that comment. I don't know that a young kid would.

Dan Sullivan: I'm not saying it's conscious. I'm saying that's an internal decision that's made. You know, I mean, I don't think it's too radically different than, you know, I like hot dogs. I don't like spinach. You know, in other words, I think we're decision-making creatures because we have to be. Because, you know, we can only think about one thing at a time, but just in the face of non-comprehension on the other people, which I sensed to a certain extent growing up, that I was having experiences and I was thinking about my experiences, but when I brought up the topics with other people, there was a non-response, there was a non-comprehension about what I was talking to. And I could have turned off doing that before and gotten interested in what they were doing, or I could have just gone deeper. And then I doubled down on what I was interested in, you know, irrespective. I said, well, there will be a time when I am not living in this town anymore and I'm not with my family. There's going to be a time down the road where, you know, I'm among people who comprehend me. Or we have conversations where we both comprehend what we're talking about.

Jeffrey Madoff: So this raises an interesting question that's also highly personal. You know, you have told me a number of times about in both looking back and the change that happened when you when you met Babs and drinking and so there was a time after you left home or whatever that you know, that came from somewhere. And you were also fortunately able to right that ship over time. But you look back at that and I mean, you don't avoid that topic. Was Dan different then or was Dan coping differently then and learned a better way to do it?

Dan Sullivan: Well, you know, I kind of think we do the best we do at any point in our life with what we have, our knowledge and our skill. I don't think at any time do we see the full implications of what we're doing in the present moment. In other words, it's guesses and bets, you know.

Jeffrey Madoff: Like so much in life, yes.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, I think the future is all guesses and bets. And you get punished if you make, you know, there's a reward and punishment, and you try something and it doesn't work, that's a punishment. You try something and it does work, it's a reward. But here's something, Jeff, that I have a pretty good grasp that, and I've had it for a long time, that if my life was a failure, it really doesn't matter that much to other people. You know, it's, yeah, I'm one human out of, the scientists are indicating that over 100 billion, you know, humans. I said, I'm one out of 100 billion. I mean, I just don't see how, in terms of the impact on other people, if my life was a failure, if I was unhappy, if I was a miserable, unhappy person, it wouldn't really matter that much to anyone else. It won't change the course of human history, you know? And so I have a sense that, I can have complete ownership over my life and do anything I want, and I don't really need anyone else's permission to do that. So there's sort of a sense of personal freedom. And I think I've had that from a fairly early age, that if you didn't make a big deal about it and everything else, you could pretty well get away with almost anything you wanted to do.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, it's when you talk about the risks and rewards.

Dan Sullivan: Well, I was talking about punishments and rewards, but you know, there's a risk that it could be punishment.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, which is why I think most people actually rather not make the decision. You know, if you're creative and you put your ideas out there, you will be criticized for whatever reasons. And a lot of people, and I've seen this with so many businesses that I've worked with and people that I know, as opposed to going for the big reward and taking that chance of being embarrassed or not living up to expectations or just being called out in front of your coworkers or whatever, a lot of people, that fear keeps them normal, you know, from doing anything that's going to cause a wave on either side.

Dan Sullivan: But here's the thing, you used two words there, the criticism and embarrassment, okay? That's my long story, by the way. There's a story there. Anyway, There's social structures. You can take two people, criticize one and criticize the other, and one of them's embarrassed and the other one's not embarrassed. Okay, so what I'm saying is the differentiation that we're making in this podcast between seeing yourself as the same over long periods of time, or seeing yourself as consistent over long periods of time, because things do change in terms of knowledge, experience, you know. But other people's criticism is other people's criticism, or other people's criticism is who you are, you know? I mean, it's interesting information, but it doesn't have anything to do with who I am. It's just somebody else's take on the situation.

Yeah, I can't remember in my life being embarrassed by someone else's criticism of me. Okay, I can say, you know, oh, that's something to be avoided in the future. Don't get into the situation with that. But it's not an embarrassment. It doesn't make me think less of myself. And, you know, I even in my exalted state of 80 years old, insanely wealthy and famous, I still get criticized. You know, I mean, there's a lot of criticism that goes on, you know, and everything else. But it's just data. You know, it's just you know, it's not it's somebody's point of view. It's like weather. You know, it's raining today. Make sure you have an umbrella.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, by the same token, I believe that you should look at your audience before you take a bow.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And I think that, you know, some people, I mean, if the audience is the check writer, then you got to reach a negotiation.

Jeffrey Madoff: God, there's so many directions we can go with this. It's a rich topic, because it has to do with self-identity, self-perception, how you are affected by others, because to some, the notion of being embarrassed doesn't even enter into the equation. Sometimes it's because they're oblivious. Other times it's because they're confident enough that in what they're doing, that taking that risk of being embarrassed isn't a factor. Or if it is, it's a very minor, minor factor. It doesn't keep you from doing it. But you can also just be oblivious and impervious to other people's perception of you. So I think there's also a line there. All of these things we're talking about, of course, depend on someone else.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, can I bring in a thought that you introduced, which I've been pondering? And it had to do with your recasting in London of the play Personality. And the main character, you made a distinction that you felt that the new actor that you had in London was superior to the role. And you called the first ones, their activity performative. It was performer. And the other one was behavior. Okay. And my sense is that that exactly describes who you think you are. Are you performing or are you just behaving? You know the thing that I'm talking about. And my sense is if you have a sense of consistency, it's just a consistency of behavior over a long period of time. It's not a difference of performance over a long period of time.

Jeffrey Madoff: No, I think you're right. I think that's right. And the interesting thing is that both of those in their own way were good in terms of speaking about the play. And both of those were different approaches. And then it becomes, you know, subjective, what resonates most with me, you know, as the playwright, and how my intention for that character is, coupled with the fact, I actually knew Lloyd.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, you knew Lloyd's behavior.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right.

Dan Sullivan: There was a resonance of behavior between the actor and the actual hero of the story.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And I saw that immediately before we even talked about it, because you had shown, well, first of all, I met Lloyd. The second thing is I had seen the performance when he's over 80 years old that you put together with a great band in New York City. Then when I saw Cedric, Cedric Neal, the actor in London, I said, that could have been Cedric Neal in front of that band singing.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and I think that in life we go through that. There are people, you know, I get pitched a lot, you get pitched a lot. You see people pitching a lot and talking about what they do. A lot of it's very performative. I happen to personally have, when I'm watching somebody on stage, that's fine. When you're trying to somehow win me over, sell me something, whatever the hell it is, it, for me, just, it has more of a tendency to repel me. You know, and we both see a lot of that kind of performance. And I think that it's really interesting because who are you trying to please? What are you trying to get out of this particular interaction? You know, as I have said before, I have aged, but I haven't matured. But in fact, you know, I have matured. I learned that I don't have to say everything that comes into my brain. There are times …

Dan Sullivan: You have the right to have unspoken thoughts.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right.

Dan Sullivan: You have my permission to have unspoken thoughts.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. And so, you know, part of me is my sense of humor. Part of me is your sense of humor. And so, you know, when you step up to the plate, you take a swing. Sometimes you knock it out of the park. Other times you whiff it. And I was okay with whiffing it. Part of it was because the reward of the other, not to mention I would not have known what worked and what didn't work if I didn't put it out there. So I never took that personally.

Dan Sullivan: Now, the thing I did take—well, the other thing is both of us use humor as a way of checking out what's discussable with the other person. I mean, are we dealing with a narrow bandwidth or a wide bandwidth here?

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right. I mean, I think that humor can be avoidance. But for me, it's more what you just said. You know, it's, I was at a party when my kids were seniors in high school being ready to graduate. There was a party for the parents and the kids. And one of the fathers came up to me and said, you know, you've got too strong a personality. And I'm thinking, okay, where's, where's this going? And he said, you know, I think that, you know, if you just sort of laid back a bit, and people got to know you before you sort of sprung a full Jeff on them, I think that might work better for you.

Dan Sullivan: Then you would have a weak personality.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes, that's right. Which is more acceptable to you.

Dan Sullivan: That's right. And I wouldn't feel so deficient in your presence. I mean, which was the point of his story.

Jeffrey Madoff: I hadn't thought of that. But that reminds me.

Dan Sullivan: Now, that is weird behavior.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, yeah, it was weird to me, because first of all, I mean, I'm searching for a word.

Dan Sullivan: I don't think I have the word right. But sort of in Congress, there's some deep emotional turmoil going on in a person who would come up, and their first way of talking to a stranger is to make a statement like that.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I wasn't a total stranger to him. I mean, he didn't know me well at all.

Dan Sullivan: You were afterwards, though.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right.

Dan Sullivan: How to turn an acquaintance into a total stranger.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right. And I said to him, you know, when I do that, when I make some of these comments, it's really out of respect for their time. He goes, what do you mean? And I said, well, if we're not going to get along, I'd rather find out right away rather than investing six months or a year in that relationship that will ultimately go nowhere.

Dan Sullivan: It's an incredible time saver.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's what I said.

Dan Sullivan: On your part and on my part.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I'm looking out for your best interest too. That's right. And I believe that, by the way. And so then there was one of the other parents said, you're spending all your time talking to the kids. And yeah, so why don't you come up with us? Because I already know what you've got to say. And these kids are embarking on that great adventure as they leave high school and go to college. I want to hear about their dreams, their desires, what they want to do, how they view the world. You're already fixed in space, you know? And you can't say that explanation won him over, but I wasn't looking to win him over.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, it's an interesting thing, you know, I mean, just, you know, what we're talking about is how do you as an individual with a lifetime relationship with yourself, how do you experience that relationship? You know, I talked to Joe Polish a lot about this, and I think Joe is remarkable in terms of having been dealt a really bad set of cards earlier in his life, you know, of mother dying early, father sort of falling apart as a result of that experience, being uprooted every two years and moved to a new place where he had to make a new set of friends and everything like that. But one of the things I found interesting is that he's been part of 12-step groups, AA, but also drug addiction, 12-step programs, where he said, it's really weird being in the room with very famous celebrities who present themselves on the screen, they present themselves in public, of having their lives completely in order, but then discovering that they experience themselves as a train wreck, as a disaster.

And you know, when I introduced, when I compliment Babs on being the single most important event of my life was meeting her, I tell people, you know, without Babs today, I'm just a smart drunk worried about the rent. And then I, you know, I describe how she confronted me with my own drinking habits. And she said, do you like being that way? And in that question was an answer, because if you do, we're not going to have a relationship. And I got the bottom line of the question. And the next day I woke up and I didn't drink for 25 years. And I said, I'm just not going to drink. And I didn't start early. I didn't actually start drinking until I was 27. And there's some evidence from the addiction centers that usually eeal addiction starts around 13 or 14. Or maybe it is that—or it could be a result of pain, where you get addicted to the painkillers.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and the thing is that you're at 27 when everything's going downhill, and that's a way to numb it. But that also may mean if you started later, maybe the chance of getting out of it and being addiction-free is a higher likelihood.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I met once there in the, and this was in the 1970s, so I was in my thirties. I met and had about an hour conversation with a man who was the head of the main addiction research center at, I think, the University of Toronto. And we were talking, and I wasn't talking to him because I didn't think I had a drinking problem, so I wasn't talking to him about that. But he said, you know, it's really interesting, you get CEOs in. He said, we'll have CEOs, major corporations in Canada. And he said, you know, they're 45 and 50. And in terms of their public performance, they have 45-, 50-year-old capabilities. They have the intelligence for the role, they have the skills, they have the capabilities. They know how to do everything in public. But he says backstage they're 13 or 14 years old. And he said the reason is that we're confronted, especially in our teen years, with all sorts of challenges, hormonal challenges, peer-related challenges, you know, self-comparison challenges, you know, there's smart kids and not-so-smart kids, there's athletic kids, there's beautiful kids and not-so-beautiful kids. And he said, that's all design is so that we emotionally and intellectually grow. He says, that's why we do it. But if you use drugs to deaden the pain, you don't learn. So he says a CEO at 45 who's now got to come to grips, he's got to make up for 30 years in a six month period.

Jeffrey Madoff: Why do you think you started since you got to 27 without drinking? What was the crossroads there?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I think part of it was new. It was my final year in university. It was sort of fun, kind of fun. But I think more and more because it was strictly wine, there was a sugar addiction. I mean, alcohol is very refined sugar. No, I don't have an explanation for your question why I did it. It happened.

Jeffrey Madoff: So what's interesting, though, is that what got you out of that, and I think this is a general truth in life, is when the stakes are high enough, you change. So, you know, I went through a thing with Margaret and we were going through a very rough period. And she said to me, you know, if you were having trouble with a client, you would figure out a way to solve it. Is this relationship important to you? Kind of not unlike what Babs said, do you know? I think I think the end of it was the same. And when she said that, I was thinking, fuck, she's right. Hated that.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. I'm just reflecting on our conversation so far this morning. How much of my life has really been internal? You know, it hasn't been external. And actually, I'm showing up in my seventies and eighties now in a public way that most people have already done in their thirties and forties. I'm well known and the publisher that we just, our joint project on a new book, they really wanted a thing. And I just noticed that my success is happening in my late decades rather than my thirties, forties, and fifties. I was really below the radar screen for most of my life. And now I'm kind of experiencing the kind of marketplace success that a lot of people have behind them 30 or 40 years ago.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, and what's so fascinating about that is having something to look forward to. And there are so many people that get to be our age, they no longer feel relevant. That's a very tough challenge.

Dan Sullivan: But it's a very accurate feeling.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, well, that's true. And they're not relevant. It's true. But the question is, you know, to that is, why? You know, why aren't you? You know, what you have done, what I'm doing, is something that energizes us, motivates us. And, you know, that's within the grasp of people. You can do that, but you got to discover what that is. And, you know, take that risk. Because I think lamentation, which is also a Martha Graham dance number, lamenting something, regretting not doing something, gets you nowhere. But actually gets you somewhere is taking action. That was one of Lloyd Price's phrases that I liked a lot, which was, the only way to make sure nothing happens is to do nothing. It's interesting, and like you said earlier about celebrities and rehab, that what they present is all seems really together, but what their back stage is, the performance is really together, back stage is a train wreck. And at some point, the train wreck is so bad, they can't carry it out in performance anymore either.

And so I think somebody very wise said to me some time ago when my kids were little, and they were saying about some of the kids in class, because you could see certain kids acting out, in certain ways. And one of the teachers who was very wise said, if you don't give your kids attention, they'll get it one way or the other. And that's really true. And again, I think so much goes back to those early years, you know, you found a great deal of your pleasure. What I've gleaned from our conversations is you kind of found out what worked with adults. You not only had a, you know, you got cookies and milk, you know, you had your five-cookie conversation, 10 extra cookies. And that, they responded to your curiosity. Your whole adult life has been fueled by your curiosity and others' hopes for improvement.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, yeah. It was very interesting. I was talking to Hamish, our cartoonist. You know, you met Hamish. I was talking, you know, I don't know quite what kind. Oh, I was talking about dumbing down experiences for children's sake. We got on the topic, you know, of sort of making sure the child is never uncomfortable with a new experience, so you dumb it down so it's not uncomfortable. And I remember who I was very definitely, it was a New Yorker, very definitely in the entertainment business. But he was talking about his children, and he was in his sixties or seventies, and he had children who were very successful, well-adjusted in their thirties and forties. And he said, you know, what I tried to do is just jarred them with new experiences and give them no explanation of how they were supposed to think about it.

And he says, one of my favorites was taking them when they were six and seven years old to the Metropolitan Opera. And he said, I really like Puccini. So he said, I would pick the Italian ones, we like Italian more than German. And he said, I would just, I taught them that they had to behave, they couldn't run around, and they had to sit through the experience. We would talk about it later, but they couldn't fuss while we were there. And I would just let them have this experience of grand opera with the glorious music and the scenery and a foreign language. And I wouldn't explain it to them when we got away. I'd say, what'd you think? What'd you think about that? Is there anything you might look up? They could read, look up about this. And he would just ask them questions about how they would come to grips with this new experience.

And I was telling him that when I grew up on a farm and the farm season lasted from April until September, and then it was over. And my father worked at a trucking line, and I don't know if you knew this, but Norwalk Truck Line. So we grew up in Milan, Ohio. I remember that name and that logo. The school where I went to was six miles away in a town called Norwalk. And in 1950s, Norwalk Truck Line was the largest independently owned truck line in the world. They had 800 trucks. And they went from Boston to St. Louis, mostly in the north, you know, the northern cities, Boston, Buffalo, and everything like that. And the main terminal of this entire network was in Norwalk, Ohio. And after school, you know, three o'clock, my father's shift went till about 5:30. I would go down and walk the docks.

And here I was this, you know, six, seven, eight-year-old kid. And I would just walk the docks. I would go to the dispatch room or the nerve center of this entire network where all the trucks were going out and they had pins that they would put where the trucks were and everything like that. And at four o'clock every day, I would walk to the Dr. Pepper machine. And the president of the truck line, the man who had created it, John Ernsthausen, was there. And he'd say, Dan, can I buy you a Dr. Pepper? And I said, yes, Mr. Ernsthausen, I can. And then we'd chat. And I said, how'd you start this whole thing? How'd you get started with this whole thing? It started with eggs. He got a truck in 1912, 1913, and he would just go around and collect all the eggs from the farms and sell them at the market. Then one thing led to another, and he had 800 trucks over a third of the United States and everything else. And I would just ask him questions and talk to him about, you know, what happens if a truck is on a trip and it breaks down, what do you have to do? And they says, well, they have to make a phone call back and we have to get another truck and everything. So I just kept asking him questions. And every day I got a Dr. Pepper. But my parents didn't explain it at all. It was just me interacting with the guy who created it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I mean, my both parents worked. And, you know, but when we were kids, it's, you know, you go out after school and play and you knew what time dinner was going to be. You go home and that three hours in between what you were going to be doing. And there were always these magical people in magical places.

Dan Sullivan: This is where worlds got created. No, no, and I'm serious about that, but that was one of my, you know, stimulus of this vast network, you know, that was on the big map. They had a big map and they would change the map about every two weeks because routes would change, new terminals, would come on, but I had a sense of the outside world. And, you know, I knew I wasn't going to grow up in that town. I was going to be out in the network somewhere.

Jeffrey Madoff: So what you were talking about, well, with this guy and with, you know, the Dr. Pepper guy and the guy who took his kids to the opera. So one of the things that I have, my teachers either really liked me or didn't like me at all. There wasn't anything neutral. And the ones that didn't like me, the consistent refrain was, you ask too many questions. And of course, my response would be, well, why do you say that? Don't ask so many questions. Now, to me, that's a horribly destructive thing to say to a kid because curiosity is such potent fuel in terms of like your friend taking his kids to the opera, there's discovery. And if you lay it out before they even get there, they're gonna look at it differently because you've given them signposts to look for, where let them discover that on their own.

And as an adult, also you can be wonderfully surprised by how they saw it and what they saw. And so I think asking questions, you learned really young that that could get you cookies and Dr. Pepper. I'm glad you didn't have cookies and Dr. Pepper at the same time. You had the cookies and the milk and then the Dr. Pepper later. But your currency was questions and getting people to talk about themselves, you know, and I think there's something really important and underestimated about the driving importance of curiosity. You know, because when you're not curious, to me, when you're not curious, you're pretty dull.

Dan Sullivan: I've been really intrigued by kind of what's going on in the world in the response to the AI programs that we have already in the first couple of years. And one of the things that I think is under challenge is the whole notion of expertise right now. And what I mean by that is that unless the expert is using the AI programs, there's a chance that they could be bypassed and outflanked by someone who doesn't have any of their training and experience just asking a question of the AI program. And I like Perplexity because it's up to date every day with the Internet. You know, one of the big problems is that expertise before the digital age was fairly slow moving. In other words, it took many, many years for you to become an expert. You know, there was real experts, there was real creative thinking that they were doing in relationship to information and knowledge that they were acquiring of other people. Okay.

But I think real expertise is contextual, not content based. I think it's contextual as you just understand contextually how to think about things, not necessarily the what of the thinking, but how to actually think about it. And so, but my sense is that there's a challenge now to the authority of experts. Okay. And, you know, COVID, I think COVID really exacerbated this challenge. And that's the first time I've used the word exacerbate in a podcast. I had never used that word before. Okay, you got to watch out with words that end with bait. You know, it's just you have to do. Anyway, I learned that young. And anyway, one of the things is that I think that, to a sense, all the institutions of society are based on an accumulation of individual expertise, regardless of the law, all the subjects of higher education and everything else. I think there is an authority that comes with that institution.

But to the degree it's based on content, it's fragile. If it's based on context of just knowing how to think about things because of thinking about a lot of things, I think there's a real durability about that type of authority or that expertise. But in one case, I noticed that where it's based on content, the person is no longer curious, but the ones on context is an eternally makes you curious about, like our podcast here, we'll start with the subject in an hour and a half later, just because it's contextual. It wasn't so much the content of the conversation, it's just where the conversation was going and what we were supplying with new fuel as we went along. But I've just been curious this year, and I will see at the end of today, I have a sense that the polls are really off. I have a sense that they're blindfolded and throwing darts at the wall, with some exceptions.

There's some, you know, there's some exceptions of people who have good track records in that. But I think the reason is because there was an interesting poll. You either believe this poll or you don't, but they've done polls among people who just answered a poll, and up to a quarter of them said that they were lying in response to the poll. Pollster, and it was based on what kind of response that they were going to get from the pollster. If they gave this answer, what kind of response they were going to get for the other thing. But the political polling is just one example of expertise that I think is being bypassed because people have access to information in other ways.

Jeffrey Madoff: Interesting you say that about polls. I've been talking to friends a lot about this because I share the same feeling about the polls. And what I liken it to is, remember when we were kids and you play telephone? And you know, the first person, tenth person, and how different the message became. And so what happens with polls is a few things. What you were saying, some people just like to game the polls. I don't know if this is still true, but I had heard earlier on is that the polling is landlines, not mobile. Now, I don't know if that's still true, but the interesting thing is … And who uses landlines? Not only that, is I know a ton of people that have lived in New York for 40 years and they still have their Michigan cell phone number, you know, and so it's got the Michigan area code. So how do you fit that in if you're polling in New York, you know? And the polls of polls, and averaging out what are the most, allegedly the most credible polls, to me becomes like the game of telephone. Because the more you try to do that, you're not asking the same questions, the people aren't the same, you're trying to now just, what you're trying to do is sculpt out of data a correct answer, which also introduces what I think happens more often than not, increased noise in the communication channel. So I agree with you about the polls. I don't think that they are to be believed.

Dan Sullivan: And, you know, I got really interested in this and I did a search with Perplexity. And I've got this, just this general approach for viewers and listeners today, that Perplexity is an AI program. I find it's congenial. I like working with it. I like the tone. I like the tone. It's got a kind of a nice tone. It's sort of a … helpful tone. But I asked the question, what were the 10 most significant historical impacts that happened within 150 years after Gutenberg's introduction of movable types? The year is 1455, so we're going to 1605. And it was as, what I would say, it was as characterized by turmoil and chaos, the same as we're experiencing today under the digital revolution, you know, and especially in relationship to who was the authority in 1455 across Europe, what had happened to that authority and its influence over people. And this was monarchy and the Catholic Church and everything else. And it just got turned on its head.

So I said, we've been through this before. We're a different way of communicating. It's like all the monopoly pieces go back in the box, but out comes a new board. You know, it's not as you may be the same pieces, but it ain't the same board that's coming out. And the way I relate this to the topic of our discussion here is your own internal identity based on the authority of other people, or is it based on the authority of your own judgment and experience? Yeah, that was pretty neat how I did that. And it wasn't I thought it was weird.

Jeffrey Madoff: Did you notice it was just this little, as the kids called it, a Jedi mind trick? Well, so when you talk about the challenge, to expertise or authority—and those are two different things also. I think that what we have now is tremendous access to information, but there's a huge subset of that information that is mis- and disinformation. And I'm talking about in every field, I'm not just speaking politics. And so one of the things that I think is so essential is critical thinking. How do you think about these things? Because it's pretty clear whether it's 23% of the population thinks that the earth is flat, or the moon landing was faked, or whatever, there's a big segment of the population you have to learn to ask other people about that question, not them. But the challenge to expertise is, to me, has got to be rooted in knowledge. You have to have your own expertise. And it's not just finding things online that you can then mouth, because then you're like a ventriloquist dummy.

Dan Sullivan: And are you talking here about experiential knowledge, where you have knowledge and then you test it out whether it works or not?

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, both, but I'm also talking about a lot of the challenges to expertise aren't necessarily informed by critical thinking, it's about we can now search and find just about anything and that people believe. And that's why I think critical thinking is so important because how do you ask the right questions? How do you frame the information? And that's a big thing with the polling you were talking about. How do you frame the question? What are your checks about undercounting or overcounting? You know, all of these things. And we're in such a constant hailstorm of data and information. But I don't know that there is the counterbalance of critical thinking. There are pockets of that, of course. But I think that too many people have beliefs that are unchallenged, and they become calcified into what they think is fact, when in fact it's not.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and my sense is it's not unique to our present age. I mean, there's this … I put out a new little book title, quarterly book title, yesterday. I said it's called The Good and Bad Old Days, because everybody talks about the good old days. And I said, yeah, well, you know, you got to balance that out with the bad old days. And they said, you know, what it would be great if we could time travel back 100 years, you know, to the 1920s, we could time back. You know, what an extraordinary thing that would be that you have today's present knowledge and you take it back then. And I said, yeah, but you wouldn't have any of their knowledge. They had just as much knowledge as you have today, it was just different knowledge. And I said, besides, you wouldn't have anybody to talk to after about two weeks, because you're immune to all their diseases, but they're not immune to your diseases. You'd kill them all off in about two weeks.

But the interesting thing about it, there's this nostalgic idealism about an earlier time in your life, and, you know, people said, you know, when people had very meaningful conversations around the dinner table at nighttime, you know, the family would get together and they'd have … And I said, you know, I was conscious of that for about eight years, at least eight years. I don't remember one meaningful conversation around the table. I have no, I have no experience with meaningful, where somebody asked a question and people went around and says, well, I think this or anything, you know, or anything like that. There's nothing. There was just, it was just a, no, I mean, I don't think there was anything wrong with it. It's just that your notion of what the past, the meaningfulness of the past, I have no experience of it.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. Well, I have right here, all of these audio tapes, quarter inch audio tapes that my good friend and I exchanged when we went off to college. I said, instead of writing letters, let's send each other audio tapes. And so I have this whole box of them and I'm thinking, well, this is from like my senior year in high school and freshman year of college. So 1960 or so, right? Well, ‘60, ‘67, ‘68. And I'm thinking, is this interesting? Is this a time capsule of, you know, who I was at that moment? I don't know. But I think I'm going to send it off to a place just to get it put onto a flash drive. It's worth the money to just find out. And my guess is that probably conservatively speaking, it's probably 90%, 95% uninteresting.

Dan Sullivan: Well, it'd probably be current commentary, you know, it wouldn't be … But I bet there'd be some interesting themes that you could identify that you were actually …

Jeffrey Madoff: That's what I'm wondering, yeah.

Dan Sullivan: I think you would find, I mean, knowing the kind of people that you would communicate with, there were probably some early themes that you were developing that you've been staying with for the last 60 years.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I actually have no memory of what's on these things. I mean, it was literally, you know, 56 years ago or so, 57 years ago. So it would be kind of interesting just to discover how fucking boring it might be. But I think you're right, there may be emerging themes.

Dan Sullivan: Well, the other thing is, I think there's a constant that today, if you did the same experiment, there would be part of the conversation or part of the communication that was about current events, you know, that will not be the same. But there will be some things which are, you know, probably universal, like there's universal themes.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, you and I are creating our own record.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, in fact, we're doing it. There's no time delay. If we were just talking about world events or what's going on in your life, I wouldn't do it. But if you got someone who can explore a thought and expand a thought and introduce new dimensions to a thought, that's interesting to me. I don't spend much time talking to people. Yeah, you're the most philosophical of all the conversational partners I've ever had.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, that's I guess one way I made use of my degree.

Dan Sullivan: Well, me too. I mean, my college was the great books and there's a ton of philosophy and there's a ton of psychology. You're two majors at University of Wisconsin. There aren't too many opportunities in day-to-day life to meet someone who have an appreciation for philosophy and psychology or even know that they're doing it when they're doing it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, that's, you know, you know what most people call that?

Dan Sullivan: What? Oh, this is getting really deep here.

Jeffrey Madoff: I said, it was kind of like somebody said, do you thank you for being vulnerable?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. I said, when you say vulnerable, you mean telling the truth?

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. That's right. Is that kind of like telling the truth being vulnerable?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, it's weird.

Jeffrey Madoff: Why would you do that?

Dan Sullivan: You know why? Because of that. It's a social construct.

Jeffrey Madoff: Which?

Dan Sullivan: Well, feeling vulnerable by telling the truth is a social construct that I'm going to be judged by my revealing this thought. And I said, well, is it okay for you to think the thoughts yourself? But there is a social reference all the time, you know, that somehow who you are and the meaning of you are is determined by social acceptance or social criticism.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah.

Dan Sullivan: All that tells me is I just have to change my social situation if I'm, you know, experienced, you know. Well, you know, no game in the stadium today. Let's find a different stadium.

Jeffrey Madoff: My philosophy advisor was a man named Ivan Saul. And Ivan Saul was considered the premier or one of the premier world Hegelian scholars. So I went to his office to ask him to be my advisor. And he said, I'm very depressed, Jeff. I said, why is that? And he said, I just got back from the World Hegelian Conference in Berlin and there's maybe one other person in the world that I can talk to about Hegel. So I said, well, why don't you choose another topic? He didn't unfortunately find it as amusing as you did.

Dan Sullivan: Well, you know, Hegelian philosophy is not a major exploration of humor.

Jeffrey Madoff: No, it certainly isn't. So he said, why do you want me to be your advisor? I said, because of all my professors, you're the only one that's got like eight books published. So maybe there's something for me to learn there. So he did become my advisor, but that was the only meeting I ever had with him. Never had a meeting after that with him. But in a way, it's like, when one finds themselves so isolated, and of course, he was, you know, the tortured intellect, telling his student how there's only, you know, he's so smart, there's only one person in the world he can talk to about that. You know, well, then talk about something else. Why restrict yourself?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, it's really, really, I mean, I read two or three Hegel books when I was at college. And I just have an experience of thinking from other places, especially in philosophy, that almost a lot of the really bad ideas that we’re feeling the effects of in the 21st century came from Germany or France. Yeah, America as a culture is pretty light on philosophy, you know, and part of the reason is that the Constitution is the main philosophy of the United States, and the purpose of the Constitution is to protect the people from the government, and that's a profound philosophical thought.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, it is. You know, it is, and it makes me think again, when you talked about challenges to expertise, expertise takes time to acquire. And I think it's fair that most people have no patience, that they want things, bam. And if it doesn't happen that way, either somebody's keeping something from us, there are things that we just don't know. And in the demand for the desire to know, and oftentimes that desire to know is based on fear. I mean, COVID is an example. And, you know, there was a novel virus there. We had to learn you can't find out immediately. It's going to take time. And that's true with so many things. But people don't have the patience for that.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. The other thing is that there was a lot of buildup wisdom. I don't know what your parents' relationship was, but my mother went through the Spanish flu epidemic in ‘18, ‘19, and ‘20. Her house was, she and her family were quarantined for three months. But the businesses went on. They would just check where it seemed to be breaking out in certain neighborhoods, and they would just quarantine. But they had all sorts of services of delivering food and supplies to the houses and getting rid of waste and everything. And that was in West Cleveland in 1819. And that was a much bigger killer. I mean, there were about two billion people on the planet in that time, and that one killed 50 million. You know, the First World War had a lot to do with it because there was just a real breakdown in all medical services in Europe at that time, you know, and they didn't have the level of medical services.

But my real problem with the COVID thing is, if you can't prescribe it accurately, you can't prescribe what the issue is. And the other thing we know is that it mostly killed people over 65 who had pre-existing conditions, you know. So you and I were, you know, we needed to be protected. And I, you know, I feel a little ticked off by I wasn't specially protected, you know, I wanted some special care there rather than just some general roles. I mean, the entire history of the human race is epidemics.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, yeah, I mean, in the where are just a few years between us makes a difference to a point is you are more aware than I of polio.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, I mean, I remember, of course, getting the polio shots and the Sabin oral vaccine. But, you know, that was that was a frightening, frightening time. Parents were scared to death. And actually, the first vaccines that went out, there was a problem with them.

Dan Sullivan: But yeah, I mean, well, most infectious disease on the planet is measles. You know, like measles, I mean, it's boom. It just, because it's airborne, measles is airborne. You know, that just, there's no disease that they've had, Ebola or any of the others, the SARS and everything else. None of them are as contagious. But what they worry about is what if there's a merging of measles with one of the other deadly disease? Then you got a real problem on your hands. But anyway, quite apart just from the issue is, that you'll see a real, what I would say, a more tentative attitude on the part of the public officials when something like this happens that they can't explain, that they'll just put in martial law like that to do that. They had enough knowledge to know that this was a 65-year-old and above problem. Very few children died of COVID.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. I mean, I don't know the global stats, but the main point I'm trying to make is expertise doesn't come quick. And we're confronted with a new problem. It takes time to know what the hell's going on. And then there's always that tension between the public's desire to want to know and do we have enough information that wouldn't be misleading or too early to give? Because we don't really know yet ourselves.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, So let me ask you a question. I have a new way of ending our podcast. What occurred to you during our discussion today that would make a topic for a next podcast?

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, critical thinking and curiosity are always big things to me and the importance of it. And I think if we apply this to business, it's the importance of perseverance and resilience. And all these things tie into what we're talking about today in terms of be defined or define yourself in self-image.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and my sense is that the huge difference between people who are demonstrably creative, in other words, is demonstrated by their activity, and they can do it consistently for their entire life, that my sense is that they have an internal authority that outweighs external authority.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's in itself an interesting topic, too.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and that they need the external audience, but they don't need the external authority.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, and that gets into the whole thing of, do you give yourself permission? There are all those [inaudible] terms, but there are some of those that are, yeah, I think so. I think that's another area that's quite interesting too.

Dan Sullivan: The other thing is the enormous confidence I have, Jeff, at 80 and you slightly younger, that all those people who were trying to stop us when we were teenagers are mostly dead. Or they might as well be.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, even if they're still living.

Dan Sullivan: Anyway, great, great chat.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes, it was. Thank you.

Dan Sullivan: It's better than sending recordings to each other.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, actually, I have to now send a recording to Gord.

Dan Sullivan: Thanks a lot.

Jeffrey Madoff: Take care.

Dan Sullivan: Thank you. Goodbye.

Jeffrey Madoff: Thanks for joining us today on our show, Anything and Everything. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend. For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

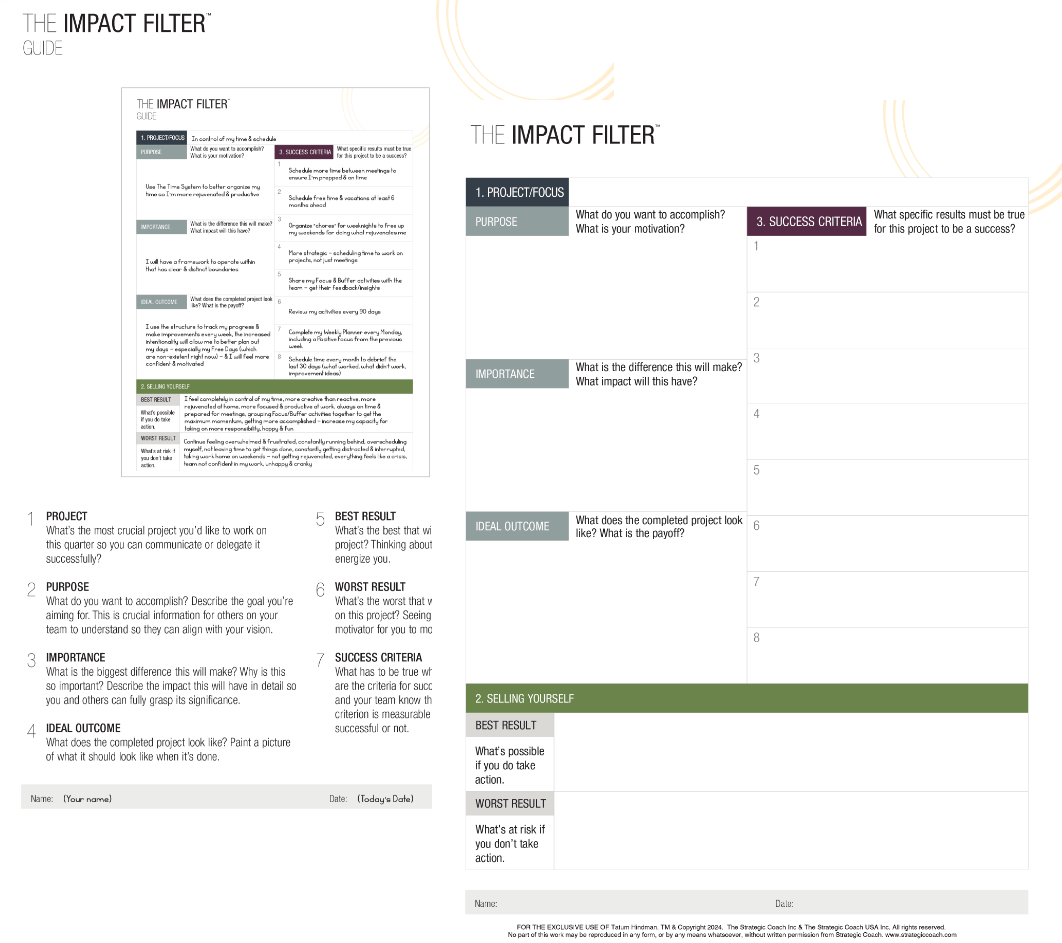

The Impact Filter

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter™ is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.