Don’t Let Technology Turn You Into A Machine

April 01, 2025

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

In a tech-driven world, can businesses stay human? Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff explore how to balance automation with genuine connection. From Chaplin to Spartacus, they explore resisting dehumanization, celebrating the human touch in business, and reclaiming creativity. They also reveal how to ensure technology elevates—rather than diminishes—your entrepreneurial spirit.

Show Notes:

Tech can empower or dehumanize. Confidence and human connection are crucial.

Customers crave real conversations, not automated prompts.

Knowing how to ask the right questions is an art form.

Real solutions that address people’s pain points require empathy and personal connection.

Layoffs aren’t a sustainable path to success (or profitability).

Inflating profits by slashing costs is a short-sighted strategy that executives often resort to when preparing a company for sale.

The most interesting people are always the ones who defy conformity.

The U.S. founders aimed to create a society where individuals could thrive.

Prioritizing quality, service, and the human touch is a smart business plan.

Resources:

Casting Not Hiring by Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff

Charlatan: America’s Most Dangerous Huckster, the Man Who Pursued Him, and the Age of Flimflam by Pope Brock

Your Business Is A Theater Production: Your Back Stage Shouldn’t Show On The Front Stage

Learn more about Jeffrey Madoff

Dan Sullivan and Strategic Coach®

Episode Transcript

Jeffrey Madoff: This is Jeffrey Madoff, and welcome to our podcast called Anything and Everything with my partner, Dan Sullivan.

Dan Sullivan: We were just talking about a general issue in the world, which is that technology, if you're not a confident, capable human being, will deaden you and make you part of the machinery. And we were reflecting on a great line that the Four Seasons Hotel use, one of the great hotel networks in the world, Four Seasons, and they have a line for all of their teams in each Four Seasons hotel, and that is, systemize the predictable so that you can humanize the exceptional. I just think that's an extraordinary short way of really putting people's attention on the right things. Jeff, what do you think?

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I love that line the first time you quoted it to me, because it's so simple and so clear yet so profound and complex. And I think it's fantastic. And you know, when you were just talking about you become part of the machine, it made me think of Charlie Chaplin in modern times. And you saw them going through the gears in the machine. You know, it's the visual of that, to me, hasn't aged because it just says it. And, you know, we're all knowingly and unknowingly, and most people I think unknowingly become an algorithmic gear in that machine.

I think it's fascinating because I think that the value of humanity and the human touch in business, which it used to be what business was, those things didn't exist, you know, you'll be reading something I had written that I sent to you before we started talking here. Who has ever had a pleasant experience going through automated prompts for customer service? You know, it's such an annoying, frustrating process. And, you know, when you used to get somebody on the line, you could actually talk to a human and get things resolved. And, you know, I think like Americans Express is smart enough to know that people want to talk to people. And so you can get to a person. Yeah, I think that that that phrase is so powerful. And what you mentioned that you think you and I have that in common, what do you think?

Dan Sullivan: You know, from the first time we met, and I'm thinking back, and I don't know if we met at Genius Network or Joe was in New York, he was introducing me to various people he knew in New York. I'm not sure what the exact meeting was, but I know I certainly met you when you were doing all the recorded interviews at Genius Network. And there was something just about your questions. I remember we sat there and we talked a lot. And one of the things that … I haven't been interviewed a lot, but when I'm interviewed, I can tell within a few seconds whether this is going to be an enjoyable experience or not. And it just has to do with, is the person asking me questions, in your case, that he's really, really interested in what the answer is going to be here? And then he'll take what was interesting about that answer to create his next question. And that's what I really loved about it.

But I think the other thing is that there was a very, very positively psychological framework to it, is that you were going to go wherever the interview went based on what the conversation was telling. And it just really intrigued me. You know, we have a lot of interest in common, but we're very, very different creatures. And I would say, is there a theme that kind of holds the whole relationship together. And I think it's this humanizing the exceptional. The more human that you can make a situation and the more exceptional you can make the performance and the result, that's just riveting for both of us.

Jeffrey Madoff: It is, it is. And part of what was enlightening to me when I was at your Free Zone conference via Zoom the other day is, it's easy for me to understand what you find interesting because I love the fact that you don't give anybody any answers. You know, you ask the right questions. And I think that's a real art. And I think that's what makes, both for the interviewer and the interviewee, that's what makes it interesting because then it quickly becomes a conversation, not a lecture, not sitting there thinking, God, I've answered this question 500 times already. So I think it's kind of fascinating, and I think you're right, but I think that that's, I mean, our mutual love of theater is an example of when you are touched by live performance and what that does, and your whole business of Strategic Coach is valuing the individual, but they have to find their answers. You don't give them answers. You help them by asking them the right questions, the tools that they use as a result of you that you create. And I think that's really kind of fascinating because I don't think there's any other way to get to the root of the issues that people are confronting without that human touch.

Dan Sullivan: The other thing that, you know, our conversations over far more than a decade now have always touched on is the environment that we're living in. Everybody's living in today, which is what I would say more and more pervasively technological. I mean, this has come up dozens and dozens of times in our podcasts and our other conversations, that there's this goal, I think on the part of some people, that we can create great creativity, great productivity, and great profitability if we can just get rid of the people.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I don't believe that you can fire your way or lay off your way into profitability. And that happens a couple of times, whether you're hitting a business reversal or you're trying to up the market value for your company. So to prepare it for sale, you falsely boost the profitability by cutting all the costs.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, you know, short term quarterly stock prices, you know, the stock value. But my sense is that this has always been there, you know, like, I mean, it just takes a very, very advanced technological form now. But if you go back centuries, there was always some overlying authority or power that wanted people to conform and just to march in unison and believe in unison and think in unison. So I think it takes a technological form today, but it's sort of an authoritarian or it's a dogmatic structure. And, you know, you can go back to Roman days, or you can go back to Greek days, and it's there. The individual who decides not to go along with the program are the interesting human beings.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, they are. And of course, there are reasons for not going along with them. I mean, you make me think of Spartacus.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Well, that's why Spartacus is so interesting. I mean, first of all, that a slave would rebel against the empire is a great story.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes. And I love the scene in that movie when they were caught, you know, the slave uprising. And so they wanted to find which one was Spartacus.

Dan Sullivan: And everybody was Spartacus.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. And that was, I thought, wow, that's so cool.

Dan Sullivan: That was such a powerful statement. But the interesting thing about that statement, now that you just mentioned it, I hadn't thought about it before you said something, is that they had bought into who Spartacus was. To a certain extent, they were Spartacus in the sense that they had bought into the, you know, the mission and the rebellion, they had all bought into it.

Jeffrey Madoff: And I think there's always the underdog story, right? That people like that. But the thing that makes the underdog story compelling is because the underdog is always portrayed, and I'm not saying wrongly, but certainly in dramatic situations in books and movies and plays, as more human. They care about other people. And the hero, and in this case, Spartacus that we're talking about, the hero is the one that puts others above themselves. So I think that that's a really interesting dynamic. Now, whether that translates into real life or not, sometimes.

Dan Sullivan: Well, I think it does. Yeah, I think it does. And I think, you know, I write a small book every quarter. Okay, it's about a 60-page book. So it's manageable in a quarter. And it's just a particular idea. The book I'm writing next, which starts next week, is called The Bill of Rights Economy. And what I've done is I've looked at the first ten amendments, which is called the Bill of Rights in the U.S. Constitution, and I've identified five ways that each amendment actually encourages entrepreneurism. The interesting thing about the beginning of the U.S., you know, with the Declaration in ‘76 and the Constitution in ‘87, is that they were departing and declaring themselves independent from the greatest empire that existed on the planet, and probably just for span, the British Empire was the greatest empire ever, and probably ever will be, just in terms of where they controlled things. And the colonies were the colonies. They were expected to do what the head office in London wanted to do. And they all knew when they signed the Declaration of Independence that they were also signing on to their execution when they did it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Would you go a little more into that?

Dan Sullivan: Well, they would have hanged. They would have hanged. If the revolution had failed and they were all captured, they would have been hanged for treason. You know, so it's an act of defiance. The characters who pulled off the revolution were a lot more interesting than the British admirals and the British generals that they sent over to put it down.

Jeffrey Madoff: And the people knew them, you know, so the other became an invading army.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. There's a very famous story about Franklin because Franklin at a certain crucial point before the revolution started in 1776, this would have been either earlier in 1776 or it would have been 1775. He didn't want the independence, he just wanted the British in London to actually recognize the North American colonists as British citizens and that they would have the same rights as the citizens of the UK. And that especially related to taxation and how they were taxed. And he went over to Britain and Franklin was a very substantial individual. I mean, he was a major thinker, he was a major entrepreneur, he was certainly a major entrepreneur, scientist.

Anyway, he went over there and they put him in a room and they just ridiculed him. They were very contemptuous of him. They said that on the boat over, he was a loyal British subject, and on the boat back, he became an American rebel, just because of how he was treated. And he was the most reasonable, in many ways, if you read Franklin, Franklin was a very reasonable character. And he said, you know, we got a good thing going here. We just have to get an agreement with how they're going to be treated. And, you know, are we going to just be treated as there were people to take from, or is there people, you know, is it a give and take? Is there going to be a give and take here? And that situation, that circumstance, when he was ridiculed and, you know, they insulted him and everything else, that was the break with. It's always contempt that breaks up relationships.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. That's right.

Dan Sullivan: There's no coming back from contempt.

Jeffrey Madoff: No. Well, because that also shows that there's no trust anymore.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: Were you, by the way, referencing Walter Isaacson's book on Franklin?

Dan Sullivan: No, no, I wasn't. This was from another reference. I've read a lot about that period. I'm very, very interested in that period, but it was very daring. I mean, it was very daring what they did. Plus, it was a unique situation because these were substantial people in the colonies. I mean, you can't find another colonial situation in the world that would have that amount of entrepreneurial spirit, on the one hand, and the other thing, just the intellectual capability of that whole group of people. They were very, very well-read, very articulate people, and not just the ones we know, but the others who signed on and were part of the beginning. But the whole thing about the Bill of Rights, right from the first to the tenth of the Bill of Rights, the Ten Amendments, it's that there's two things. The Constitution right on the first page says this is the supreme law of the land, okay, it's not the president, it's not the Congress, it's not the Supreme Court. This document is the Supreme Court, is the supreme law of the land, but those first 10 were actually the objections that the public had of the Constitution itself and said, we don't trust you. We don't trust you.

And Hamilton was the great example. Hamilton wanted America just to be a bigger Britain you know, with aristocracy and the military officers in charge. And he wanted it both North America and South America. He said, we're going to have the whole Western Hemisphere. But Madison said, you know, but we're just becoming what we're trying to separate ourselves from if we go in that route. But the big thing is that that document is to protect the people from the government. The whole purpose of the Constitution is to protect the people. In other words, allow us to be human beings, allow us to have our own ambitions, allow us to develop our lives in the way we want to develop it. So, that's what, coming back to the theme of humanizing the exceptional, these were exceptional people. They were creating somewhere where the individual could really become exceptional.

Jeffrey Madoff: And it's interesting because are the people when you say they were, these were really exceptional people.

Dan Sullivan: I think they were.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, I don't argue that. But can one act on their exceptionalism in circumstances that don't require it?

Dan Sullivan: Yes, yes, I think they can, you know, because I think they're, I think we would both agree that Churchill was an exceptional person, totally exceptional. But it was also a factor of the times that he was in and that he could fall so far early on, you know, at the Boer War with Gallipoli and Gallipoli.

Jeffrey Madoff: Also, that's right. And he recognized the threat of Hitler.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: And Chamberlain was oblivious, or I don't know if he was oblivious or what, but certainly didn't seem to get it. But it was those exceptional times that called for exceptional actions and exceptional people.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, he wasn't called back until they were just about ready to go over the cliff, you know, as far as the war was going.

Jeffrey Madoff: And his, you know, his resurrection, so to speak. Although you have to give it to him, he was consistent throughout, you know, in terms of what he saw as a threat.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. You asked the question, is it possible for people to be uniquely exceptional? And I said, yes, there is. Number one, I think entrepreneurism is the main vehicle there. And what we're talking about in the book, Casting Not Hiring, is that if you treat your life and treat the organization the way you organize life in a theatrical way, you can be absolutely exceptional. Well, and that's why we love theater. That's why we love theater, because it humanizes the exceptional.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes. Yeah. And it's interesting because when you look back on the example we're just talking about, Churchill, he literally wore different costumes depending on who he was talking to. And, you know, whether he dressed up as a high street person or he dressed up as a soldier, you know, and I think he was very aware of the audience he was playing to or at least thought he was playing to him. And so, you know, he was a star. He was theatrical and he had these unique attributes that made him stand out. And he enhanced those attributes in terms of what he did.

Dan Sullivan: Churchill Museum in London, which is down in the basement, right next to the war rooms, you know, where they basically planned out the whole war. So there's two parts to it, but one of them is just on Churchill, and there's an engraving on the, he says, I believe all human beings are worms, but I am a glow worm. Star Theater, I think he's a glow worm, you know. But the, you know, we started on this particular conversation, is that I think the tyranny now is in the technology.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, so tell me what you mean by that.

Dan Sullivan: Well, that if you're willing, technology will turn you into a machine. If you just want to go along, more and more, you will be asked to act almost like a machine. Don't have an opinion, don't have an objection. You know, just go along. Just go along with the algorithm. Don't rebel against the algorithm.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and if you are complicit, you have become a part of it. And I think that the gap between technology, as we're talking about it, which initially seduced the same way that television did, appeared to be giving you free entertainment. But what they were doing is selling their audience to advertisers, which is the same thing that Facebook did, the same thing that Instagram did, the same thing, all of these.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, if they say it's free, you can know that you're the product.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's exactly right.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: Why do you think it is that there seems to be this blind faith, I would call it, that this being technology is a good thing?

Dan Sullivan: Well, you know, I don't have anything personally against technology, and I don't think you do either.

Jeffrey Madoff: I don't. No.

Dan Sullivan: You know, the way I've analyzed technology is that it's automated teamwork. So all human activities, eventually, if they're, you know, if they're really effective, isn't so much on one person's role. It's humans working together and having a way of passing off part of a project to another person in the project. So there's a certain efficiency in teamwork. And then it can be observed what these humans are doing, and it's always repeated, it always is done the same way. So why don't we just automate it and essentially free the humans up to do something or get rid of the cost of the humans. It's either for a negative reason or a positive reason. And that just happens at every level of human activity, that things which once were just human beings doing, now it's machines doing the same thing as the humans are.

The big crucial is, once the humans no longer have to do the automatic activity, do they get freed up to do creative activity, or do they just disappear and are eliminated as a factor? And I think that's the real issue here. Is it a negative thing you're doing this for, because you don't wanna deal with the people, or is it a positive thing? Is it that you think that the humans are capable of much more and this repetitive part, we don't want humans doing this anymore? We want them to do creative things.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think that big businesses are always looking at how to increase profits, especially public companies. Because they're beholden to their board of directors and their stockholders. So I think that that's where the focus goes. So I don't think that it's an altruistic, we'd like to free these people up to be able to do more creative things. I don't think they care. I think it's how it impacts the bottom line.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, it's also the people in the corporations, the public corporations who are responsible for, you know, quarterly earnings. They're mechanized human beings to a certain extent. I mean, they're just passing on. We're mechanized, so we'll pass it on so that everybody should be mechanized. So we meet our quarterly reports.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, and I think you can't eliminate from that that the higher up executives, CEOs included, the more they up the profits, the more they up their own income. And so they care, you know, I think you have mentioned this before, which is their number one concern is their own future worth the company. Or another company.

Dan Sullivan: Because the average for a CEO, if you take the, you know, the big listings, 500, you know, Fortune 500 or any of the listings, the average time as a CEO is six years.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I have been in a number of situations where the CEO or president of a company, the company that hired them realized they made a mistake. But they made a mistake, they discover it two years in. So the question is, how do we get rid of that person? And the way they get rid of that person is paying them a barge load of money. And then the confidentiality agreements and the non-disclosures as to why. So then we end up hearing because they wanted to spend more time with their family. And I certainly believe that. So I think that, you know, it's set up in a way that the individual ultimately isn't valued. That's expendable because if the result of me making you expendable is my bottom line goes up.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. You know, we were just sharing some information about incorporated companies in the United States and, you know, I did a search and it came up with that. There's about 33 million as of the end of 2023, there were 33 million-plus incorporated companies. And so I put in how many of these are privately owned and it was 99% were privately owned.

Jeffrey Madoff: It was fascinating, yes.

Dan Sullivan: And then I asked another question. This is an AI search and answer search. And I said, can you break out that 99% in terms of how many employees? 1 to 10, 10 to 50, 50 to 150, 150 to 500, 500 plus. And 74%, it was 1 to 10. So the thing is, these are privately owned, so they're not controlled by Wall Street. They're not controlled by the quarterly earnings. You know, they may have investors, but it's not that impersonal. I mean, you don't even know who it is at Wall Street that's actually doing this, what you're doing, and it's a market. It's geared to be impersonal. You can't operate a system like that on a personal basis, although I'm sure it does happen.

But the big thing that I'm saying is, and this represents 45% of all the employees in the United States, that 99% in privately owned organizations, that's 45% of the total employees. So it's almost equal to the employment impact of corporations. And so my sense is that if you're going to say humanize the exceptional, start with the privately owned because you can get right to the owner who is not there for six years, who's not there and they're thinking of their career after. They probably, in many cases, created the company. They're the owners of the company and they're the founders of the company. And so if you want to get the message to them, you can get to that individual.

Jeffrey Madoff: I also think it would be interesting that those numbers that you researched, my guess is the public has no idea how high the percentage is of these private businesses and the employment, all that kind of thing, because as viewers, we're pretty much, you wouldn't be wrong. You would be misinformed. But you wouldn't be wrong to be thinking that we have vast majority of public companies, and they generate all the money and you have the vast majority of the money, which isn't true. But how else are you going to get people to get involved in the stock market, the derivatives market, and all the other things? You know, so the perception is, you know, it is more, it's more valuable to Wall Street to have you believe that the case is that public companies are what drive everything.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Well, I think the, the other thing and you're heading, you know, you just opened another door with that comment is that, um, this is a crucial object of public reporting and public news, what the major corporations are doing. And one of the reasons why corporations are valuable to governments is that if you want to find out very quickly what direction the economy is going in, you just make 500 phone calls with the largest corporations and you'll get some sense. If you were doing it on the basis of the privately owned, you'd have to make 50,000 phone calls. So I think it's a matter of just efficiency of reporting, measuring and reporting that you have these large corporations. But my sense is the perception of life as hell in the workplace comes much more from the people who are employed in large public corporations than it does in the privately held companies.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, I think you're right. I mean, we've seen that.

Dan Sullivan: I think they're more technologized. I just think that the large corporations are much more where the thought is always on people's mind, because it sounds good to Wall Street, that we've just eliminated a thousand employees. Wall Street says, that's a good sign we can get people to invest a little bit more in this company.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, there isn't really any advantage Wall Street to, I'll give a specific example, Kohler. It makes faucets and plumbing stuff and so on. And it's now the, I think it's third or fourth generation of the Kohler family.

Dan Sullivan: Privately owned.

Jeffrey Madoff: Privately owned. And I think they're seven, eight billion. And why is Wall Street going to talk about them? They got no stock to sell. There's no way for the public to participate, if you will. And you know, it wasn't all that long ago that when you were dealing directly with brokers for the companies, and another name, or my other name for stock brokers, is salespeople. You know, because they basically sell the stocks the company's taking a position in. And there's no money-making incentive to cover those private companies. And so again, the perception gets created that if you wanna get in the game, here's the game. And now a more pure indication of this, which I find actually repellent. You have a phrase that I love and we've talked about it a lot and use it as guesses and bets. Everything's guesses and bets. The betting websites, where literally, and I saw this last night and read about it, that they have people placing bets on the degree of damage of the Los Angeles fire. And how venal can you get that you're willing to so literally profit from tragedy? And that just gets me. I mean, that's just, you know, so well, it's certainly against my values.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Yeah. Well, it's not the game that you and I play for the last 50 years. Ours is strictly relationship-based. We bet on relationships.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and by the way, it's not the last 50, it's 75 on my end and 80 on yours. I mean, it's not like we had some revelations.

Dan Sullivan: But my sense is, because I've dabbled with AI since it's been a big deal over the last two years, I've dabbled with it and I find it very interesting. It's actually the way I'm approaching it is that what happens to my intelligence if I'm creating teamwork with artificial intelligence? That's what I really find interesting about it. One of the things is I'm finding that my way of thinking about things is gradually changing. And in particular with one particular AI tool, Perplexity, which I find very congenial. I just find it very, whoever the makers of this are, you kind of get a sense they're sort of congenial human beings.

But what I've learned when I read something, my news is mostly on the internet. I have some great sites that have great articles. And a thought occurred to me, Jay, I said, Jay, I wonder, I'd like some more history on this. And I'll go to Perplexity, I say, tell me 10 important historical facts about this thing. And, you know, three seconds, four seconds, I do it, and I read it through. And what it's gradually doing is that I don't have an immediate response to anything that I read, because there may be a background here that I don't understand. The other thing is, I'm completely convinced that there's no one reason for anything. There's 10 reasons for something, you know, as you do it. And it's just making me a little bit more wise, if I can use that word, wise about how I respond to news or how I respond to claims. I'd just like to know a little bit more background about this, and I find that very satisfying. That's technology that's actually making me into a smarter, more effective human being.

Jeffrey Madoff: No, I think it's you who are making yourself a smarter and more effective human being and how you use that tool, which is the technology, in this case, the tool being Perplexity.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, and the mere fact that what you want is more context and background before you form your opinion is, you know, which is called critical thinking, you know, so that you're bringing that to bear on these things, as opposed to taking things at face value, I think is what needs to be taught in schools. People need to know how to do that. And so, yes, there are tools out there that can help you do that. But, you know, if you weren't the inquiring mind that you are, none of that would make any difference. You know, I think that that's what's so important is these things are tools that can be used for good or that can be used for bad.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I just saw a little quip about cats and dogs, and they said, you know, dogs, it's a much more lasting relationship, because dogs are looking for a master, and cats are looking for a servant. And I said, you know, the whole question is that, and when it comes to our relationship with technology, who's the master here? Who's the master in the relationship with the technology? And it seems to me it's almost binary, the choice you make. The tools are either your servants or they're your master, and you're gonna get caught. There's no in between. There's no in between except anxiety and worry. That's the only thing in between them. So my sense is that what we're talking about in Casting Not Hiring is that you constantly strengthen the unique individuality of every person who's on a team in such a way that they'll use technology in such a way that technology is a servant, not a master.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right, right. And so one of the big pluses of the speed of retrieval and the pattern recognition that's embedded in AI, using that for medical research. Okay, so there's tremendous advantages that it can bring, life-saving advantages that that can bring to the table that would take people much, much longer to do. And there it's, you know, certainly a tool. I mean, when x-rays happened, it's not like everybody wanted x-ray machines in their own home. But, you know, everybody's got at minimum a phone and most likely a laptop.

Dan Sullivan: But they exist now.

Jeffrey Madoff: The phones?

Dan Sullivan: No, no, but you can actually do an x-ray with your phone. I'm not sure it's x-rays, but it's sonograms. You can actually do that with your phone. I just want to get in one point about this, because I've really followed technology. I'm connected with Peter Diamandis and Abundance A360. And we started this in 2013, so we're more than a decade. And Peter brings people who are on stage, who are making all sorts of predictions about the future, you know, electric, you know, EVs, they're talking about virtual reality, they're talking about all sorts of breakthroughs. The only one that has performed over the last 10 years where the progress is actually greater than it was predicted 10 years ago was medicine. And I think the reason is it's the most intensely human thing that you can make progress on is medicine.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, yeah, I think there's so many impacts that that has, you know, and I think that goes hand in glove with longevity, which people are absolutely fascinated by. You know, I think if you're leading a good life, you don't want to die. And I was watching, I didn't watch the whole thing yet, but Don't Die, Brian, the documentary about Brian Johnson.

Dan Sullivan: And, you know, he's got this Olympics that he's created with a major testing company, Rejuvenation. It's called the Rejuvenation Olympics.

Jeffrey Madoff: No, I don't know about that.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, it's based on blood tests. It's a company called True Diagnostics. And so he did a joint collaboration with True Diagnostics. They're the most extensive blood testing technology that actually they can talk about the rate of aging, how fast you're aging. That's basically what they measure. It's very, very interesting. And then he put up the money for this Olympics, the Rejuvenation Olympics, you know. And so other people, they have to go through a doctor or a clinic, and their results are put in, and then they give a ranking. It was up to about 2,000 people who were doing it. It's very interesting.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I wonder, I think of the war on cancer. you know, which has been going on a long, long time.

Dan Sullivan: It's a long war.

Jeffrey Madoff: Pardon? You've heard of the hundred years war?

Dan Sullivan: Yes. This is one of them.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. But I always, I like looking at what are the historical antecedents, you know, what came before that was like this, you know, I mean, smallpox. Well, yeah, but I'm, I'm talking about like the search for the fountain of youth. You know, that's not a new idea. You know, The Portrait of Dorian Gray, whatever, whatever. There was always some kind of devil's bargain with staying young forever.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, and look, I want to live as long as I can, as long as I have a good quality of life. And I'm having a pretty good time. And so I'm not, I don't want to shuffle off this mortal coil any sooner than I have to, and as long as I can be, have fun, and not be a burden to those who care about me. But it's interesting because, God, on a profound level, and I think it's important to look at these historical antecedents, these things aren't new. The ability and measurement and criteria and insights we may have into things, but it's like when you read that book that suggested to you that you enjoyed about, I'm blanking on the name of it now, about the goat, the guy that was implanting goat testicles.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: But he pioneered marketing.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: It's just, you know, I mean, it was just absolutely, absolutely—was it was called Charlatan?

Dan Sullivan: Was that a doctor in Kansas? And I'm not sure he was a doctor. He called himself a doctor. I think he did a two-week course somewhere, you know. But a fascinating guy and he was a phenomenal marketer, broadcast marketer, but he vastly expanded the technology of radio. And literally gave country music its real foothold in the American public listening to country music, because he had a million-watt radio station. And it was illegal in the United States, so it was a mile across the U.S.-Mexican border. But the interesting thing was, he was called a charlatan about all the doctors, but if you look at the actual history of medicine when he was operating in the 1920s and ‘30s, there were a lot of, you know, official doctors who were doing charlatan, you know, they were doing fraudulent things.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, you could get your hair cut and your liver taken out at the same place.

Dan Sullivan: In the same chair.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. How should I tilt this? A little off the top or should we take out a vital organ?

Dan Sullivan: It's like the Monty Python, you know, the Life of Brian and the Roman centurions there. He says, flogging or crucifixion? He says, crucifixion. He said, no, no, I'm kidding. I'll get over there and get flogged, you know. Yeah, but there's two ways you can get a haircut. So, you know, the haircut where you really get taken for a lot. But the other thing is that he was a criminal. There's no question what he was doing was criminal. But he was certainly tapping into what an aspiration there is for people to lengthen their lives and hold on to their health. He's tapping into an aspiration, you know.

Jeffrey Madoff: What's interesting to me is, so you and I are both old enough to … we're just old.

Dan Sullivan: But not enough.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. The enough is later. I'll second that. When the change happened, I don't remember, I wasn't alive when the big radio piece of furniture was in the room and people would sit around and watch the radio aside from listen to it. Not much happened when you looked at it, you know. But when television came in, and television was regarded two ways. One way was window on the world. And the other way was the vast wasteland. And both were true. It was a window on the world, and it was a vast wasteland. It was both. I think that that's been true with every major technological advance. There are those that are using it for the general good, like what we're talking about with medicine and so on, and there are those that are using it to monetize whatever they can, however they can. And that includes information about individuals, all kinds of stuff. You know, so those two things, window on the world, vast wasteland, can both be true at the same time.

And that's the concern. It's not the concern, that's how I look at the technology. Depending on how you use it, it's going to determine that. But I think that there's a lot, you know, it was also totally unregulated because nobody even knew what to do with social media when it first started. Nobody knew what, couldn't know what it was going to grow into and become. You know, so I think that's kind of interesting. And is it this week they're gonna be ruling on TikTok? Which is also interesting, because my guess is a lot of people in the government are woefully ignorant of what that even is. I'm talking about TikTok and those aspects of social media. I don't know who they're getting information from.

Dan Sullivan: Well, the big aspect is that it's controlled and owned by the Communist Party of China. I mean, if they were an American made technological platform, we wouldn't be going through this conversation.

Jeffrey Madoff: I agree, but I think that it's also interesting because that concern that there is information being harvested from U.S. citizens, which has, you know, been happening since this started.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: And, you know, how much do I trust Facebook's harvesting of information or Instagram or whatever?

Dan Sullivan: Google.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. But also we have a tremendous desire, this I'm talking about humans, for answers that most people don't realize the complexity of the question. And, you know, like you were talking about yourself earlier in terms of how you will look up the history in the context of something, most people just want a simple answer right away. Even though a true simple answer isn't there. And I think this extends to everything with, when I look at the stock pages and I see all those numbers and decimal points and all this, I think, God, there must be a way to collapse this into some formula that is foolproof. But we've had too many recessions, too many bank collapses, the prime mortgage, junk bonds, on and on and on and on to realize, no, this is just something else that can game the system until it doesn't and then it collapses on itself. And we've seen that on and off constantly with crypto. Now, you know, because people think it will be favorable legislation about it because of the current administration, that crypto stocks have been going up again, but those things are a total rollercoaster.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, guesses and bets.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. Yeah, that's right.

Dan Sullivan: I mean, the future is just guesses and bets.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right.

Jeffrey Madoff: But I would say that the more that the new thing that's being created takes in humanity, the better bet it is.

Jeffrey Madoff: Absolutely. Absolutely. And the better bet because, you know, you talk about values and you talk about value monetarily and people are willing to pay more for that. Those who can, of course, are willing to pay for that. And so you go back to Four Seasons Hotel and their operating philosophy, which is so brilliantly stated in that one sentence. If you'd repeat that for whoever's listening, that would be good.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Systematize the predictable so that you can humanize the exceptional. And what they mean by that is that their hotels are so well-run, they have such great systems, and systems are how people provide service, how they provide a first-class environment, but they break that down into a whole set of little rules. Number one is that if you're a member of the Four Seasons team of a hotel and someone from the outside of the hotel comes to you and asks you a question about something that they need to do in the hotel, you stop what you're doing and you conduct that person to the person who can actually help them, then you come back and you do your job. Rather than saying, go down here, take the stairs, none of that, the person actually does it. And so you always get what you want when you go in because their rule is that they're going to help you find what it is that you want, get to where you want to go.

The other one is that when you're doing your job, do your job and look for one other thing. So an example would be a maid cleaning a room And she notices that there's lipstick on the wall or something or there's a light out in the, you know, one of the lamps lights out. She then reports on that one other thing because she's looking for the one other thing to report on. But this is, that's exceptional that you're going above and beyond just job description. You're moving into the area of exceptional. You know, I've been going to Four Seasons hotels since 1980, so it's 45 years I've stayed in 34 of them, and it's uniformly high quality. You know, I've never had a situation where I was disappointed. And if I was disappointed, the way that they responded to my disappointment was better than if it had been right in the first place. You know, it's really an extraordinary, and they have 130 hotels in the world now. They're not a small operation, but each of them is like a separate little theater company.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think that what you're saying, which resonates for any business, is quality and service under the umbrella of the human touch is a smart business plan.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, yeah. Yeah. And it's a strategy you can stick with.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right. It's well-defined. I mean, you know, I've worked with Ralph Lauren as a client for 38 years, and I have to say that's what Ralph did. That consistency that you can count on is so important. And I think that the Four Seasons, I love that summation and that quote, because I think that people are rediscovering as a result of, I think, frustration with how technology has taken over so much stuff. I mean, Four Seasons would never have, no good hotel would ever have automated check-in, although you could, but it's the hospitality business. So if you don't have a human greeting that person and welcoming them to what's gonna be their home for the next X number of nights, then you lose a huge opportunity to touch that consumer and hope to build loyalty like you have with them at work. You've been a 40-year client, 45-year client. So I think it's really, there's lessons to be learned from this that are not just philosophical, but it's good business.

Dan Sullivan: One of the things, there are some things that are telltale signs that what is being stated is not the truth. I notice it a lot in restaurants. One of the things is that you go and you sit down at the table or you sit down in the booth and there's a statement of their principles of running the restaurant. And you know, you want to leave right away if they tell you what their principles are. And they're saying, in spite of what your experience is, know that these are our principles. I mean, Four Seasons never tells you what their principles are. You just feel what their principles are. The second thing is that they don't give you menus anymore. They give you a QR code, and you're supposed to use your phone and pull up the QR code. And I really like menus, physical menus.

We were at a steak restaurant last night in Chicago and it was quite dark. It's, you know, it's nicely designed and everything, but it's, you know, it's seven o'clock in January and it's dark. So they have lights on, but they're very subtle lights and everything else. And the menus come, they're big menus, big book, and you open it up and they're backlit. They're backlit. I said, that I really like. I really like. I hate having to take, you know, ask for a flashlight or something to actually read the menu. The other thing is that you go to a restaurant and where you can really tell it is in the restrooms, there's a broken tile on the floor. Okay. You know, they have tiled floors, but one of them is broken and it's chipped a little bit, or there's a crack in the mirror or there's a mark on the wall and you go back two weeks later and it's not repaired. You know, something's really wrong with that restaurant.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. There are those telltale signs, the clues that something is not working right.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, absolutely.

Jeffrey Madoff: I was at a restaurant, actually in Chicago, really cool restaurant. And they said, I had the thing in the middle of the table that you could use a QR code. And this was an expensive place. So I asked the waiter, I said, do people really like prefer, you know, the looking at a menu on their phone? And he said, they hate it. I said, so why do you do it? He said, we're phasing it out. We're having our menus printed. Now the customers hate it.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, yeah. I mean, it's the most impersonal thing in the world.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, it's also part of your marketing if you have a nicely designed menu.

Dan Sullivan: I love menus.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, absolutely. Absolutely. And I don't want to sit there with my appliance. I usually, by the way, screw up getting the QR code in.

Dan Sullivan: You're making me work. I don't wanna work. Yeah, I came here to relax and have a good meal. You're making me part of the staff. I don't wanna be part of the staff.

Jeffrey Madoff: I have to figure out how the menu works.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Then you tell me what tip I should leave at the end.

Jeffrey Madoff: I know, I resent that too. Was the service great? Was it okay? You know, whatever it was, I can figure that out and tip accordingly.

Dan Sullivan: And my behavior will demonstrate whether I was happy.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Check out my behavior.

Jeffrey Madoff: So what we kind of have wrapped this one up already, but of course, kept going anyhow. But my major takeaway was how important the human component is, how much more valuable that's going to become. And as a sidebar, what you were talking about, which is the importance of vetting information that has some kind of impact, vetting that information, learn more about it before you pass it along. So constantly, and I think you and I both love doing this, constantly be educating yourself, be curious and educate yourself. So those are some two pretty big things that I got from this. What about you?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, I'm really interested because I've really followed technology for about 50 years. And since the word microchip was first being used publicly, it had been around backstage in the technological world for about 10 years, but the word microchip was used. And, you know, there were some great articles, principally the technology writer in the New York Times produced about five or six major articles on the microchip back in 1973. And they said that this is going to be one of the great changes in human history. And that it's an invention that can be used on almost every existing invention. So cars are going to be transformed by this. Every mechanical process is going to be transformed. Organizational processes are going to be transformed. But it's also an invention that can be used on itself to produce even more powerful microchips. And I said, this is really cool. You know, you're right at a major historical breakthrough or watershed.

And one of the predictions that the New York Times writer made was that very large organizations with multiple levels of management are going to find this very, very hard to respond to. Because the speed of the technological change that's going to come about because of the microchips will be faster than the big organizations can respond to creatively. And that it's going to spawn all sorts of new kinds of entrepreneurial activity. And that was the magical phrase for me, because I had this idea of coaching entrepreneurs. And I said, you should pay attention to what this new event and the new transformation is taking place in society.

So I've been really following this. And my sense is that this background story, this big narrative of what technology is doing to all human affairs, all human activities, seems to be the major narrative of all other change that's happening in society, and that there was no training or education about this anywhere in the educational system. And it's not really talked about as a thing, even in the business world. You know, they talk about particular devices, or they talk about particularly new tools or anything, but they don't talk just about the general environment. And my sense is that if you're ignorant about this and you're not alert about this, that my sense is that the technology will make you part of itself and it'll ask you to think and communicate and act as if you're a piece of machinery and not a human being.

Jeffrey Madoff: I agree. It's funny because on the book that we're doing together, Casting Not Hiring, I am writing it as opposed to I'm not trying to have AI do it because I want a unique voice for us. Because the more that these areas intrude, the more homogenized the output becomes. And so I think it's important and incumbent on you and I to practice what we preach. And that human touch, which I don't think either one of us would ever abandon, is just so important. This has been great.

Dan Sullivan: Yep. We talked about something and we talked about everything around that something. So within the framework of anything and everything, I give us an A today. I'm not a real high grader, but I thought it was an A today.

Jeffrey Madoff: I will accept and agree with that. Thanks for joining us today on our show, Anything and Everything. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend. For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

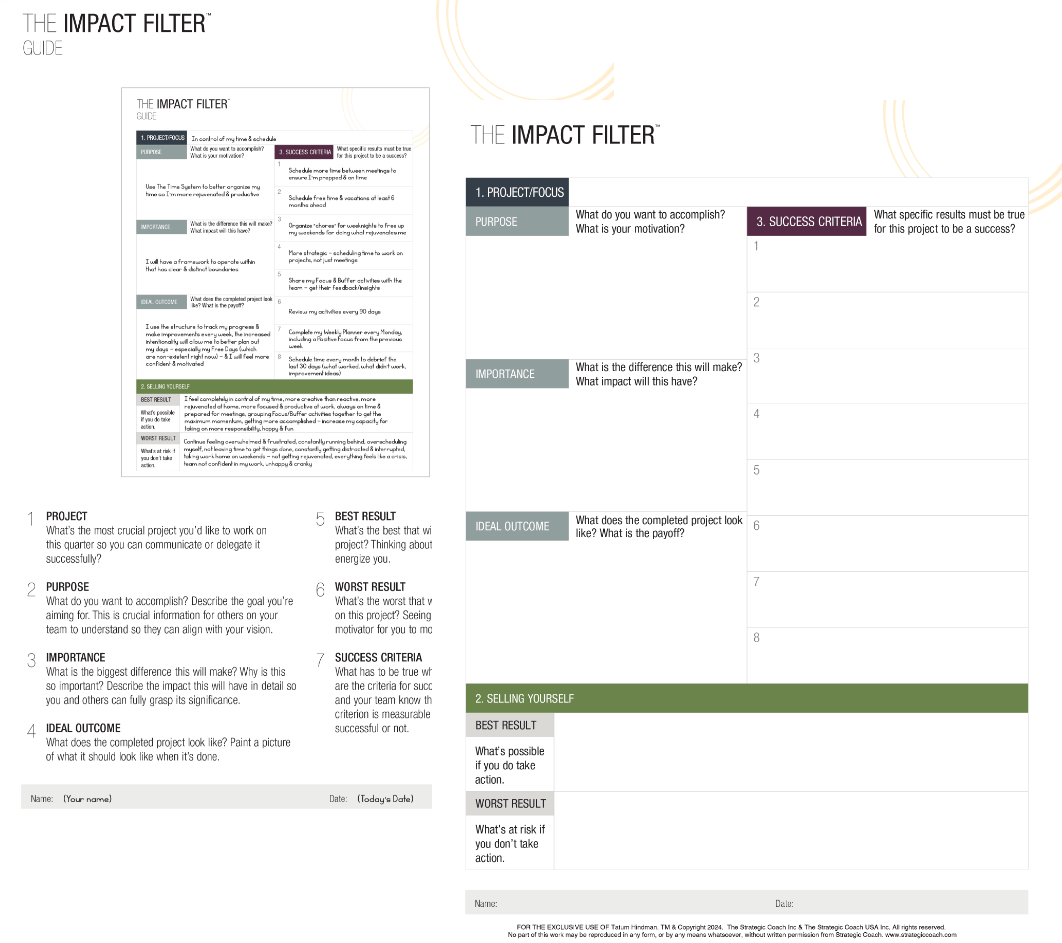

The Impact Filter

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter™ is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.