Are The Games You Play Competitive Or Collaborative?

April 08, 2025

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

What effect do the games we play have on us—and what do our motivations for playing them say about us? Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff discuss the kinds of “games” that are interesting and beneficial to entrepreneurs, and why you don’t have to choose between passion projects and commercial projects.

Show Notes:

Competing with yourself means measuring your progress against your previous performance, not against other people.

Life itself is the ultimate game for self-competition.

If you’re questioning what you’re doing, ask yourself what you could be doing instead.

Games have a binary outcome: victory or defeat.

Some people are born with a competitive chip in their brains, and some aren’t.

This applies to creative individuals too. Creativity can be collaborative, but many creators believe their creativity has to be better than everyone else’s.

People who oppose a system often create something directly related to what they resist.

Truly passionate people cannot not do what they’re doing.

Entrepreneurs have the self-awareness and confidence necessary to confront the marketplace head-on.

An opportunity only becomes one when you recognize it as such.

Resources:

Your Business Is A Theater Production: Your Back Stage Shouldn’t Show On The Front Stage

The 4 C’s Formula by Dan Sullivan

Learn more about Jeffrey Madoff

Dan Sullivan and Strategic Coach®

Episode Transcript

Jeffrey Madoff: This is Jeffrey Madoff, and welcome to our podcast called Anything and Everything with my partner, Dan Sullivan.

Dan Sullivan: One of the things that we talked about was games, talking about critical thinking, and we were talking about passion, and we were talking about, is talent the most important thing you need to be a successful entrepreneur? We're going to weave those four subjects together. First, with the games, I'm not big into games where I compete with other people. I'm into games where I compete with myself. And I find the best game that lends itself to playing against yourself is actually life itself. And what I'm saying is that I'm competing with my previous performance. And I actually have forms and everything that I use every day. I keep score.

But I've never enjoyed individual games. I think we had a discussion about this, where it's one person against another person. I've never enjoyed that. I have enjoyed team games where there's a score for the team, but you did want to beat the other team. You wanted to win with your team. In other words, you wanted to contribute as much as possible with your team, but you did want to beat the other team.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, games to me, when I was a kid, there were marathon games, and those marathon games were like Monopoly, where we'd leave it set up as long as we were playing at Sonny Lowden's house. I don't think you knew Sonny Lowden. And as long as his mother didn't come in and say, you've got to clean off this table, we will leave the board set up with the markers. And it was just a fun way to interact with each other. When I got into sports, like in wrestling, which was a one-on-one sport, although team numbers would win, but it was one on one.

Dan Sullivan: It was big town, too, wasn't it?

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, in high school now, but in university, it was college. You know, in sports is kind of a different animal than the games I got used to play cards. My grandfather taught me. I was very, very close to him. By the time I was five, I could play poker, Pinocchio, and gin with the adults. And that was fun. My uncle Phil, he died owing me $1,800. Tried to collect it from his son, but I couldn't get it. You got to get it on the day. I hadn't been that sophisticated in business yet. But it was fun playing with my uncle Phil because each hand I would beat him, he would just laugh, thinking, I don't know how you did that. And he would just laugh. And I said, that's so I'm glad you're enjoying it, Uncle Phil, pay me. But those kinds of games, I have now zero tolerance for games. It's been true for over 40 years now.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I can't play games anymore. I don't know why. And I sort of if I'm doing this, there's something more important that I'm neglecting if I'm playing the game.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, one question that I think is always important to ask yourself if you're doing something and questioning it is, what else could I be doing?

Dan Sullivan: I do that all the time.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, me too. Not that I necessarily hate it. I'll still continue to waste time doing whatever I'm doing. But I do hate it sometimes. You know, but what I wonder about games is the cultural aspect of games. You know, what you were saying is basically that you eschewed the competitive aspect of it, and that to me was fun for a while, but I wondered, you know, In games, it's very binary. You win or you lose. And I think that there's so many comparisons, especially, you know, business and sports and all the analogies between the two. And I wonder how does that affect us when we think of an activity as either a win or a loss. And I wonder if that came from, you know, our sense of play, or did our sense of play come from that idea of winning or losing? Is that necessarily the best way of looking at something?

Dan Sullivan: I haven't done a deep study on it, but I suspect it was connected to warfare for men, that the games that you would play, and it brought out certain skills that were useful for warfare. I just happened to read something about Rome, that there was a while where the gladiators killed each other. But then they ran out of gladiators, so they decided that they would have a less lethal form of the gladiator games. Then it was betting. There would be betting on the activities. But the other thing is, I think some people are born with a competitive chip in their brain and other people aren't.

I was born with a collaborative chip in my brain. I like collaborating. I just like putting my skill together with someone else's skill and producing something that's bigger than both of us. So since I don't have the inkling, you know, to do it, I can't make a judgment about people who love it because I just don't find it attractive, you know. I like creativity and I like collaborative creativity. And there's competitors in creativity that what they create is better than everybody else's creativity. But it's never really interested me.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, and there are people because of their creativity, they've carved out a niche for themselves.

Dan Sullivan: I like having a monopoly, though. I do like having a monopoly.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, monopoly has got to be the ultimate capitalist gameplay for kids, you know, where you develop these properties. And by the way, you know, Monopoly was created by a woman who never got credit for that.

Dan Sullivan: And I think she was a socialist or something, wasn't she?

Jeffrey Madoff: I think you're right. I think there's a backstory. I think she was a Marxist, you know. But she was short of cash. It always strikes me that people who are against the system then create something that is directly related to the system that they hate.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, it's an interesting thing.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, and it's interesting with Monopoly because it's truly an entrepreneurship game. You know, if you develop the properties, and you've developed the right properties, and people happen to land on them, you know, you can …

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, make sure it's Boardwalk.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, yeah. You know, and then there was Baltic, you know, the slums.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, don't wanna go to Baltic.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes. Yeah. But I wonder if, in terms of, from the time we were kids, we play these games where people win and lose. And like you, I consider myself a collaborator. That's what's really interesting to me because the effect of that collaboration with the right person, like I'm fortunate enough to have with Sheldon Epps, for instance, Personality is for me much more satisfying. And it's not about being able to exercise my will, but I'm wondering if in our culture, if you don't win, do you lose?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, occasionally. I mean, is there a thing about always winning? You have to win. I mean, I think the culture's got everything in it, you know, and competition is one of it. One of the later topics that we had today was passion. You talked about passion and follow your passion. And we were at a conference where Palmer Luckey is there. Palmer Luckey is an interesting, very, very interesting tech guy. And he's about 30, 31, 32, I think, right now. But when he was 17, he was a gamer. He, you know, the online gaming, he was apparently very good at, created a lot of games himself. But he created the Oculus goggle, you know, the thing that fits over your face.

When he was 17 or 18, I don't think he went to university or anything. I think he just came up very inventive. And Facebook offered him $2 billion because Mark Zuckerberg is hyper-competitive. They paid him $2 billion when he was 20 years old or something for it. But he's not an employee. When you buy somebody, then you've turned an entrepreneur into an employee. And there was a falling out, and he left. But he had his $2 billion. He has $2 billion. And now he's developing weapons for the U.S. government. And he can apparently do it at one-tenth the price, much more effective weapons. Sensors, sonar sensors, land sensors. He actually was developing a sensor for the part of Los Angeles that has the winds, the canyons, where it could sense just a certain temperature of the ground. And immediately, he would put out a warning. And they wouldn't go for it. They wouldn't go for it. They didn't. He had an early warning system.

But he's just somebody who's going to do well. And he had a reason I'm bringing this up. He said, I'm totally against following your passion. He says, what you do is follow your capabilities. And he says, you develop certain capabilities. And as those capabilities meet certain opportunities and whatever it does, you follow that. So I thought it was really a line. I just don't believe in this passion thing. But the thing I feel about that is that I just read what you wrote about the passion. And I said, you know, the people I really bet on are the people who cannot not do what they're doing. So would you say that's passion? There's just something they cannot not do. And they'll do it whether they get paid for it or not. There's something that they have. And I will always bet on a person who cannot not do the things that contribute to me. Yeah, I think that, you know, in a sense, you're asking, so what? I don't know what passion is, because how do you experience passion? What's that feel like? Is it emotional? Is it intellectual?

Jeffrey Madoff: For me, the passion, I recognize passion is when I am completely engaged in what I'm doing. And that that engagement has a sense of gratification and fulfillment. I mean, the fastest way for me to glaze over is somebody explaining the deal they just did. I don't care.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, that's not your passion.

Dan Sullivan: No. Yeah, but it probably is theirs.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, or I think there are people that need a metric to measure their activity.

Dan Sullivan: Sure.

Jeffrey Madoff: I do. I do. Well, it depends on the metric for me. So for me, is this something I want to be doing? Why am I doing it? It's not any kind of crystals and pyramids in terms of following passion. You know how hard I work to try to do what I'm doing. But the old saying about, but if you really love it, it's not work. I mean, I think that's true for you, too.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: Would you agree with that?

Dan Sullivan: You know, it's easier to say it at 80 than when I was 40. I think I'm in a position right now where I'm only doing what I love doing. I don't think I do any other activities besides things that I really love doing. And I've been very strategic about that over the years, making sure it lines up with how I'm best paid. And I think that's what entrepreneurs are. Entrepreneurs who are individuals who have enough self-awareness and enough self-confidence that they can hit the marketplace head on. Very few people can hit the marketplace head on. They need a buffer, they need intermediaries who will guarantee them an income and they'll, it's the intermediary's job to find a usefulness to what you're doing and you're guaranteed.

And I don't need the intermediaries. I can go out and I can just meet people and I can understand what they're up to, I can understand what they're trying to achieve and through questioning and giving them a process that I can do it. And I've been confident about that from a very early age, that I can always find a way to make money in a way that suits me.

Jeffrey Madoff: We share that. I have the same. And it's interesting because it goes hand in glove with your concept of there's two sales, and the first sale has to be to yourself. And to me, If you have sold yourself, you're on the passion road. Because then it's something that you really wanna do and that you will undertake despite the challenges. When I was seeing this play, it's actually auditions, auditions for my play when we were in London. And this has happened in Chicago, it happened in Pennsylvania, it happened in New York, all the different auditions we held and so on. And I thought about, wow, these people, against all odds, statistically, they are really dealing in lottery world. But they're compelled to do this. And I'm so, I have so much gratitude for the fact that they do because the joy or thought that their work gets from others.

And I know from like seeing audience responses to Personality. One of the reasons I wanted to do a play was, and I didn't know what the story was going to be, and I didn't know I wanted to do a play until I met Lloyd. And then everything changed. That wasn't part of my to-do list, but it happened. And when I'm asked, which I've been asked many times, oh, is this a passion project or is this a commercial project? And my answer is yes. It's both. You don't have to choose. And you know, money is the fuel that drives things, allows you to drive things forward. So it's a business. But am I passionate about what I'm doing? Yeah.

And I have never seen an entertainer of any sort, whether it's a dancer, a musician, an actor, whatever, that I didn't think was, how can I say this? Their passion for what they were doing was clear, and they happened to be at that crossroads. If it's not a product of nepotism, they happened to be at that crossroads where their talent and the application of that gave them the opportunity to bring that to fruition in front of other people that could help finance their efforts by getting booked. I'm sure Meryl Streep was not a great business person, but she was a staggering talent who I am sure brought passion to everything she did, or at least most things she did. And I think that a life without passion is a life that is not well lived.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, one of the things in looking at our topics today, I was saying, you know, it's one of those things that at a certain age, you know, I used to think I understood other people's relationships, why they were together. And as I go along more and more, I find I'm more and more ignorant about why two people have a relationship with each other. But the same thing has to do with talent and ambition. And opportunity, more and more is, I don't know why I've been lucky, and I don't know why my talent lined up with my opportunities. But it did. It did. And I find myself less and less judgmental about people for whom it didn't. I just don't. I said, I don't know. I don't. And I have what I would say I'm less confident about and say, well, if you just did this and this and this and this, it would line up, because I don't know if it's true for them.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. That's what I call the myth of replication, that somehow if you followed these same seven steps as if it were a recipe, you would have the same outcome as that person who is, by all accounts, successful at what they're doing. Well, you can't replicate those things. The whole argument about that is a fool's errand. Because you have to understand that you are different than them, the circumstances are different, the people they met, all of that kind of thing. But I'm curious, when you talk about luck, how do you define being lucky? What is being lucky?

Dan Sullivan: Well, here again, luck has a backward interpretation. So, I hadn't really thought about this before, I hadn't really talked about it. But I think a lucky person is someone who can reinterpret any experience that they've had to see where the value of it was for them, whether it was a good experience or a bad experience. And they have a transformational attitude towards their experience where they could have said this didn't happen because of something. And it comes out bad and they say, you know, I've just not been lucky. But I think that's a fundamental attitude. You know, I think it goes very deep. I think it goes right to the center of who you are as a person.

For example, we didn't have money growing up. You know, we had enough, but we didn't have anything extra growing up. And so if you wanted money, you had to go out and find a way of getting the money. You had to do something and get paid for it. And I had that very early. I had that very early. You know, as a child growing up, I knew how to see where I could be useful and then possibly I could get paid for being useful. And I was on the lookout for that. I was on the lookout for where I could do it. So I've always had the ability to have money.

So is that luck or was there something that I just observed that if you want money, you have to do something valuable to someone else before you get money? And other people, I was just reading in the Wall Street Journal on Saturday that 23% of the graduating class of Harvard Business School in June 2024 don't have jobs. They don't have jobs. I was sitting there saying, well, did you think that getting a degree from Harvard got you a job? You know what I mean?

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes, yes, Bob. Yes, they did. Yes, they did. That's right. Yes, they did.

Dan Sullivan: And I said, well, then, you know. But what they find, you know, that, what was his name? Ross Perot, who got Clinton elected twice in the nineties. And he graduated from Yale Business School. And he went there and he said, I just want to congratulate all the A students, whatever degree they have. Would you have all the A students please stand up? And they all stood up. And he says, let's give them a hand. He says, okay, now I want all the C students to stand up. And they all stood up. And he says, A students, I want you to turn around and look at your future employers. He says, because what I've observed that A students are trying to get really good grades because they think really good grades get them where they want to go.

C students want the business models. So they do the minimum to get a grade because they've already started businesses. And they just want to see if is there anything there that can actually help you run a business. And he says, very seldom do the A students go, they work at investment banks or they do this, he says. These students are just finding the bare minimum of time to actually get their degree because they're already running businesses, you know.

And so, you know, you use the word in your fourth one, talent, you use the two words, you used perseverance and resilience. And then I was saying, yeah, there is enormous perseverance and there is enormous resilience. If I look back, I've been very, very persevering, but only with things that I turned out to be really good with. So is it the talent that gives you the confidence to persevere?

Jeffrey Madoff: I don't think so. I think it's a mindset that gets you to persevere because …

Dan Sullivan: I mean, there's obviously lots of people who persevered with something that didn't get them anywhere.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. And that's why I'm saying that I think perseverance is a mindset, it's not a …

Dan Sullivan: It's a separate capability.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. I think that's a separate trait, if you will. You know, to the ability to persevere and to, you know, the resilience to bounce back from difficult situations. You know, I think that I mean, by this, I mean, I think we both have that, too.

Dan Sullivan: I think we're talking about that. I mean, I went 10 years with creating the coaching company before I was breaking even. And I went through two bankruptcies. I went through a divorce and everything else. And I remember talking to a banker. I had a line of credit, which I had to go in and tell him I couldn't pay it back. And he was a nice man, you know, he wasn't mean with me. And he said, you know, when we first talked, he said, you know, you can be employed as a writer, you can be employed as a layout artist and everything else. So when are you going to give up this nonsense of trying to do this new thing?

I said, there will be no going back. I said, I'm just not smart enough yet to know how to do this, but I'm going to be smart enough in the future, so I have to do it. And I said, thanks for your help. I'm sorry it didn't work out, but there's no going back. And then within about two months, I met Babs and Babs was really crucial to me having a front stage and a back. I was just all front stage and forgot about the back stage. And she really knew back stage and then went up and everything else, but I would never. Once I'm locked down, there's no going back.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, see, I think when somebody says to you, when are you gonna stop doing this nonsense?

Dan Sullivan: Nonsense, yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, that tells you more about them than it does about what you're doing. And oftentimes what I think the resonating point is, is that you're somebody who's going for something. You're motivated, passionate, you're going for something. He's not. And any time you meet someone such as yourself, it becomes a reminder that he never took the risks, he never took the chances. And I really believe that because so many times what people say isn't a keen observation into you. It's a window into them and what their issues are. So why would you say that to somebody? Why would you demean what someone else's efforts are? When are you gonna quit this nonsense and do what? Do what you're doing? What am I giving it up for?

Dan Sullivan: I didn't think of that at the time. I didn't check in to see if there was a possibility I could become a banker.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes, I haven't deposited those thoughts.

Dan Sullivan: You know, part of it is that you take your vision seriously, but you don't take yourself that seriously. And what I mean by this is that there's, you know, there's eight, nine billion people on the planet. If this particular one fails, it's not, it's not threatening humanity's future. But the one thing I found, especially when I had the double day of a divorce and bankruptcy, I actually felt kind of freed up. And one of the reasons is that people leave you alone when you're both divorced and bankrupt. You know, they said, Dan, we're having a little party, get together for the occasion and wondered if you could just come over for a couple hours and just tell us about your divorce and bankruptcy. They don't do that. They leave you alone. They give you your privacy and everything else.

But I had about three months after that. And that happened in August. So it was, you know, about three or four months. And I just said, you know, you're completely freed up from everybody else's expectations with this. And now the question is, what do you really want? What do you really want, you know? And that's a turning point in my life. That was 1978, and that was a complete turning point in my life. I said, just keep doing what you're doing, get smarter at it, get better at it, and that's it.

So I think there's something about the passionate person or the driven person. They're not doing it for status. They're doing it to develop a particular capability that if they're really good at it, they can get really unusually paid for it. If they can pull it off. And I think, you know, the biggest risk is that you're risking yourself. In other words, you're kind of putting your life on the table and say, I'm just going to risk my entire life to pull this off.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. But, you know, when you can't imagine, as you're saying, can't imagine yourself doing anything different. And that you're not dissuaded when someone in an authority position tells you, when are you going to give up this nonsense? You know, I mean, at a certain point, there's some people to find that they were delusional and maybe that person was right. But I also think that's where perseverance comes in. And I think, I didn't quite get the definition from you of what you think luck is.

Dan Sullivan: Well, so, you know, the thinking tool that I created for Strategic Coach, it just said that one of the things I've noticed among entrepreneurs when they become really successful, not all of them, but some of them is that I did it all on my own. You know, it was me that got me where I am. And I said, 50-50, it was you that got your, but if you had been born in Ukraine near the front lines, not so lucky. So, you know, one of the things I said, you know, I put down on my sheet, I was born healthy and fit. I've always been healthy and fit and smart enough to succeed. Whatever I was up against, I was smart enough to succeed in that situation. I think that's lucky.

You can be born not fit and healthy, and you can not be born with enough brainpower to succeed. I was the fifth child in a big family, but I have big age gaps, six years one way, seven years another way, and there was just me. And I just had my parents to myself for almost all my life. And both of them were fifth children. My dad was a fifth child in big family, my mother. And it was like, we knew the rules, we understood each other. I consider that very, very lucky. And, you know, meeting Babs was very lucky, you know, all the really great creative partnerships and relationships I've had, I consider that really, really lucky, you know.

And what I'm saying is that, you know, when you're born, you realize fairly quickly that nothing that's here was actually created with you in mind. You have to come to grips. I mean, you have to adjust. You have to negotiate with reality when you're here. And so, I mean, I'm answering your question. I'm attempting to answer your question here is that there's things that you can be grateful for, you know. And so I choose to say those weren't as a result entirely of my own efforts that the good things that happened to me, they came along and It happened, you met right people at the right place at the right time. I don't think that's necessarily your capability that does that.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right, well I think though, close to or adjacent to luck is opportunity. And I think that an opportunity is only an opportunity if you recognize it as such. And if you don't, it passes you by.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and I think that preparation has a lot to do with it, you know, that you were able to see the opportunity because you were prepared, you had prepared your mind, you know. Let's just take Personality, for example. You met Lloyd because there was a documentary filmmaker. Who identified Lloyd for you?

Jeffrey Madoff: A guy by the name of John Bonanni, and John was the executive producer at Radio City, and he hired me to create the 75th anniversary film for Radio City Music Hall. And we became friends. And he was friends with Lloyd. They went to the same eye doctor, you know, so they were in the waiting room at the same time. And he called me from there. And that's how contact started.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Now, I think there's luck involved in that.

Jeffrey Madoff: And not immediately. I mean, I recognize there's the opportunity to do a documentary about him.

Dan Sullivan: And then when you did the documentary, you kind of saw the opportunity to take it further.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes. Yeah.

Dan Sullivan: And it's funny because it was definitely good luck for Lloyd. It wouldn't have happened.

Jeffrey Madoff: No, I think that's right, because it hadn't happened and hadn't even been close to happening. So, you know, I think that you're right. But, you know, it's interesting. There's luck. There's opportunity. There's, you know, when those two meet in a certain way, it's serendipity. And I think that going back to where we started in terms of passion, do you think a few years ago, I'm not talking about in your first 10, well, whenever, I guess, in your history, would you have defined your passion attitude, if you will, towards Strategic Coach and the creation of it, would you have said that was just a keen business proposition that you knew would turn out well? Or was it the foundation, a passion you had for the kind of interaction and the way that you could think about what you were doing? Where'd that come from?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, definitely the latter. Yeah. No, and it comes from my childhood of just being interested in adults. And when I'm eight, I'm asking 78-year-olds, what was going on in your life when you were eight years old? Yeah, that's totally passion. I have a passion in understanding other people's stories. I have a total passion for understanding. And it did take me two or three decades to get a business model for that passion.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. Well, I mean, I think that that's, you know, the issue for a lot of people, I think it's twofold. One is recognizing what it is that makes them feel the best about themselves.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: And I think doing what you do at Coach, not only makes your clients feel better, I think it makes you feel better. In terms of what you do, and you're in the position that you get to do that all the time.

Dan Sullivan: And get well paid for it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes. And I think that that's something that we both have. And could I have done other things? I mean, I believe there's a number of other things I could have done quite well. I have the capabilities of doing things well like that. It's just I didn't want to do any of those other things, you know, because what was missing was I wasn't passionate about that. So, I don't agree with, you know, the naysaying about follow your passion, because I think, you know, throughout history, those that have excelled have had a passion that they were following. You know, who was, what great artist, what great writer, what great politician, what great anybody got to the fact that we know who they are, but they were just emotionally neutral. Nobody. Nobody. You know, so I think it's important to examine what we even mean by those words before we can make a conclusion about where that person is at.

Dan Sullivan: Do you think there's a place in this for it's sort of like getting the right hand dealt to you? You know, for example, I know people who are just sort of scattered, you know, they're just sort of scattered and. the nature of their scattering is that they can't focus on the thing that means they don't have a central thing that, you know, that they cannot not do. Do you think that's possible? It's just a bad hand.

Jeffrey Madoff: I don't know if it's a bad hand. I think there can be a few reasons why that happens. And I think that one of the reasons why that happens can be a fear of commitment to something, because if that something doesn't work out, then in your mind, you are a failure. As opposed to looking at it positively, well, you tried something, you learned something, you've moved on from there. And so I think that a lot of times when people are that scattered, even with serial entrepreneurs, I think that it's not necessarily, maybe their passion is in starting things, then they lose interest, but it's also I think not committing to something. I think commitment is really an important part as long as you're committed to something in terms of, you are committed to building Coach and doing that. And when you say the hand you were dealt, you were dealt a lot of hands over those 20 or 30 years until you figured out the business model. So it's not like it happened instantaneously and batteries included. You had to discover that about yourself as I think we all do. And I do believe, I think, that there are people that, at least it seems to me, they were born to do X. You know, whether that's a prodigy in music, and that's a case where a capability drives it, but sometimes people find out later in life, I wasn't doing that for me, I was doing it for my parents, you know, and they're living through that, and I don't wanna do that. you know, there's no one reason. And I think what's fascinating is the fact there is no one reason. And discovering who that other person is and who you are in the process is, you know, what to me is so fascinating. You know, everybody's kind of a riddle.

Dan Sullivan: You know, it's really interesting to me that my father was an entrepreneur. He was a farmer first and he failed and then he became a landscaper and he succeeded. But of the seven children, I'm the only entrepreneur. And I've talked to some of my siblings about that, that dad couldn't do this, and dad couldn't do this, and dad couldn't do this. And what I saw is dad had great freedom. He had great freedom. What I was picking up on is that for the longest time, there was no security, but there was enormous freedom that he could have. I picked up on freedom and they picked up on lack of security. You know, that's what they do.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. Well, that's the old “Me and Bobby McGee” song, you know, freedom's just another word for nothing left to lose. You know, and that wasn't a direct quote, but I screwed it up a little bit, but I think that that's true. But it's also interesting. So you have how many siblings?

Dan Sullivan: Six.

Jeffrey Madoff: And of those six siblings, since what you do is so otherworldly different than what they do, how curious are they about how you've done what you've done?

Dan Sullivan: I didn't hang around with them. You know, the older ones were older and the younger ones were younger. So I hung around, basically hung around with adults. But the other thing is there is the family you're born into is a bit of a roll of dice. The family you develop in the course of your life is by design. And so the other thing is that I have the opportunity to finance their grandchildren, so I've financed about 13 or 14 of them, where I've paid for half their tuition going through university. And they appreciate Uncle Dan. They like Uncle Dan. Uncle Dan's a good guy, and everything like that. So it doesn't, but the thing was, I really appreciated my invisibility as a kid. You know, I could do things, go places and do things, as long as there was a set of rules I had to follow and that was not onerous and everything like that. So I'm interested in them. Like when we talk, I find out about their life, but it's not reciprocal, you know?

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think that that lack of curiosity, you know, says something. And, you know, one could get different messages.

Dan Sullivan: I'm not the only thing they're not curious about.

Jeffrey Madoff: Did you see this Encyclopedia Britannica?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: Not interesting.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, it's interesting. And just as we get close to the end here, the critical thinking one was an interesting question that you asked about critical. How do you know what you know? And how do you why do you believe what you believe? I think it's all being aware of experience. And what is the experience for me? It's what is my experience? It tells me that works and that doesn't work. You know, that's how I think I've developed my critical thinking.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. I mean, I think that that's I think we could do a whole segment on that, because I think it's something that's sorely lacking in terms of the teaching of critical thinking, and why is that important? Because I am always very interested in why do people believe what they believe, and why do you believe that? Which goes along with the thinking about thinking that you're so fond of, and I think that critical thinking, which also requires something else that we both believe strongly in, is context. And I find it interesting, especially in the times that we're in now, but I think it's always been really important.

But one of the things that I loved about my major, I had a double major in philosophy and psychology, and the thing about philosophy was it was all about critical thinking. What kind of an argument, what kind of logic and what kind of an argument could you construct? And God, I was looking back through, I had saved some of my college papers and Margaret found one of the blue books from a final in symbolic logic. And there are like these 15-page equations that wherever my brain was at that point in my life, it's not there anymore. And I was like, we can get hieroglyphics. It's like, wow, I actually knew that stuff. And I think that's one of those things. It's funny. It's like my kids, learned a totally different math or learned math in a totally different way than I did. And by the time they were in fifth grade.

Dan Sullivan: You weren't any help.

Jeffrey Madoff: None. That’s right. I didn't recognize it as math. Yeah. Well, Johnny has five apples and Jimmy has two apples and he takes, you know, that was how it was when I was growing up.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. You gotta learn how to make change. That's the most important lesson. Or just take credit cards. Here's something I feel is very strong in my thinking, that you need to know how you think about things because you want to attract like-minded people. And that's become more and more restrictive as I've gotten older because I find that I am looking for people who are entrepreneurial thinkers, you know, more and more and more. That people who realize that if you want something, it requires a commitment, it requires courage, you know, you have to go through it. Long period of courage, short period of courage, it goes through courage.

And the big thing is the acquisition of new capabilities. I'm really passionate that you create your future through the acquisition of new capabilities. So I look for people who have that mindset, don't have other reasons why things happen. I think that's my sense. And I'm sure there's other reasons why it works. I'm just only interested in linking up with people who have that attitude.

Jeffrey Madoff: For me, it's, there's a few a few tenants to it. If you are curious, if you are intelligent, if you are empathic, and if you have a sense of humor, we're going to get along. We can differ in any of those areas, but if those four character traits, if any one of them is missing, pretty good chance our relationship won’t work. And so it's interesting, because I think it's not that I want to attract like-minded people. It's that I am attracted to people who seem alive and engaged and interesting. And that's the thing to me.

Dan Sullivan: I'm attracted to people who find me interesting.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, that goes way back.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Coming up on 81. Yeah, yeah. But I think it's very, very interesting to know these things. I think critical thinking for me is that you're aware of how your brain works. And I think that's very, very important that you be aware of how your brain works. Even the biases that you have, why you have the biases, I think that's very, very important.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and that you're curious, or at least I'm curious, about how other people's brains work. Why do they believe that?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, they don't work the way mine does. And that's important, that's important.

Jeffrey Madoff: I think so.

Dan Sullivan: So what did we get out of this? I found the four of them that you gave me were really interesting, but I thought that they were interesting together. But I do know that based on our conveying our different histories to each other, we've done a lot of experimenting on this. How do you size up other people? You know, I mean, I think that we're both deeply interested in how is it because you have to guess and bet with new relationships. You have to bet. And how exactly are you becoming a better guesser and a better better? That's an interesting topic.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes. Yeah. Well, which, you know, is about being present in the sense of listening to the other people that are around and getting a sense of, you know, who they are. I mean, there are some people that have the capability of engaging people right off the bat. There's other people that are more observational and they don't put themselves out there until they feel safe, you know, to do that. You know, as I get older, realizing I have less time, I don't wanna waste time with people that we're gonna discover, eh, we don't really have anything in common anyhow. And I can also embrace people that there are things that we disagree, but that's fine.

And those reasons, you know, the reasons for disagreement are understandable. You know, and I think that too often because of how isolated people are, that shuts off. It's just all silos. And I mean, when I was, I was a pretty popular kid in junior high and high school, but I was never, and there was a pretty cliquish school I went to, but I was never a member of a clique. I had friends, diverse friends throughout and was never part of a clique. Because I never saw any reason to. Why would I want to just know one type of person?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, that would be true. You know, that'd be true with me, too.

Jeffrey Madoff: I mean, it's not as much fun.

Dan Sullivan: Well, it's the Groucho Marx thing.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. About the club.

Dan Sullivan: I'd never be a member of a club that would have me as a member.

Jeffrey Madoff: I love that. I love that quote.

Dan Sullivan: That's the story of the man who's marooned on an island. He's Jewish, and he's very handy. So it's 20 years to go by, and boats come by, but a boat sees something, there's a reflection or something, and they come ashore. And he's building an entire town inside the jungle. It's got stores, it's got restaurants, it's got a dry cleaner. But down at the end, there are these two really, really interesting buildings. And he said, what are those two buildings? He says, they're synagogues. He says, synagogues? Well, why do you have two? And he says, well, that's the synagogue I go to. That's the one I wouldn't be caught dead in.

I mean, if you're going to bring the culture forward, bring the whole culture. But it's interesting. And, you know, the section I just wrote on humanizing the exceptional, I make the point that the more things become technologized, the less interesting the humans are. And that's why you need theater as a transformative quality is because it makes human beings interesting.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. And people that take a chance. People that put themselves out there, people that don't, you know, in one of our past conversations, you told me somebody thanked you for being vulnerable, and you said you mean being honest.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, telling the truth. That's right.

Jeffrey Madoff: And it's interesting that there are many people that consider that to be that truth and vulnerability, because vulnerability means you can get hurt in some way. And on one hand, you know, you can be hurt by being honest in how people may respond to you. But, you know, my feeling is, and I'm not talking about life and death situations, my feeling is that you might as well find out whether you're gonna get along sooner rather than later. I think, you know, because then you either have more time to develop a relationship and you've made space because you've filtered out the people that it would never work out with anyhow.

Dan Sullivan: Anyway, always fascinating where these things go.

Jeffrey Madoff: Thanks for joining us today on our show, Anything and Everything. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend. For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

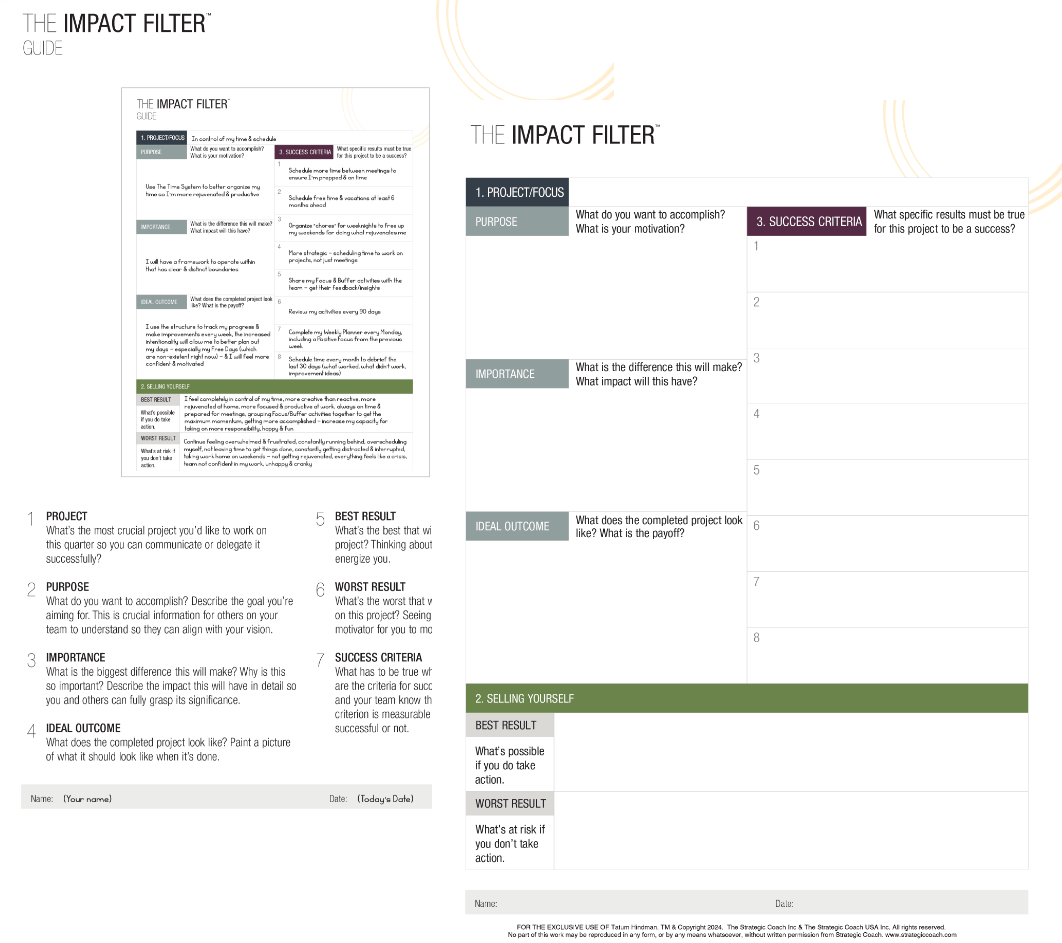

The Impact Filter

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter™ is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.