What Your Standards Say About You

April 22, 2025

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

What if predictability is the ultimate competitive advantage? Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff dissect how standards and intent create unshakable trust in business and in life. Learn why elite entrepreneurs prioritize dependable relationships over short-term gains, how to spot (and avoid) toxic partnerships, and why money is just a metric—not the mission.

Show Notes:

Humans don’t like unanswerable questions.

You can't seek answers unless you have questions, and you have to ask the right questions.

Prediction is necessary for survival, which is why we’re always looking for things we can count on in the future.

A lot of power comes with the belief that your intelligence is better than someone else's intelligence.

Thought is a luxury. Only those freed from survival mode can engage deeply with creativity, innovation, and purpose.

Humans aren’t information processors—they’re meaning makers.

Purpose is created out of greater and greater freedom of money, time, and relationships.

Money is the scorecard, not the game.

The greatest contribution you can make to another person is your standards.

Teams thrive when they know your standards are non-negotiable, even if it’s uncomfortable.

Resources:

Same As Ever by Morgan Housel

You Are Not A Computer by Dan Sullivan

The 4 Freedoms That Motivate Successful Entrepreneurs

Casting Not Hiring by Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff

Learn more about Jeffrey Madoff

Dan Sullivan and Strategic Coach®

Episode Transcript

Jeffrey Madoff: This is Jeffrey Madoff, and welcome to our podcast called Anything and Everything with my partner, Dan Sullivan.

Dan Sullivan: We were just chatting a little bit, Jeff and I were, and it was about, you know, this is really both in the realm of philosophy and psychology, which you're used to, Jeff, because you majored in both when you were at university, and I went to college where you just read the great books. They were called the great books of the Western world, and I thought some of them were great and some of them were okay. But it has to do with the tendency of people who are really smart, I mean, they're smart people, of having the need to have an idea that then, once they have that idea, they can stick with it all their life.

I just happened to mention an incident about how did everything get created, you know, which is a good question. And nobody knows how the world started, how the universe started. But psychologically and emotionally, people have difficulty just going with certain answers. And my attitude towards it, well, the reason why we have answers is that we've got to simplify the complexity of life. You know, you come up with answers for that. But it doesn't mean it's the truth. It just means that this is the way that you've found to simplify things. What do you think about that?

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, I wonder, you know, coming up with answers presupposes that there are questions. So with the questions, what were the questions about? Now, I suspect that so many things, including language, came about for reasons of survival. And, you know, simple things could be just a yell with no actual word attached to it because there wasn't language initially. And so I think that thought and ideas, according to recent studies, have actually preceded language. And that words, and this is, I think, interesting and difficult to ponder that when words didn't exist, when language didn't exist, we still somehow communicated with each other. It had to do with survival, whether it was finding a dead animal carcass to eat or a charging animal at us that we wanted to get out of the way of, or somebody fell off the edge of a cliff or whatever.

So I think that, see, this is such a big question, I don't have a big answer for it. Because I think that the answers, we always are seeking answers, but you can't seek answers unless you have questions and you have to ask the right questions. And so I'm not exactly sure where, what came from, but I do believe that survival was at the core of all questions, which is what I believe ultimately led to the formation and foundation of religion. Unanswerable questions. And we don't like, as humans, unanswerable questions.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, that works for me, what you're saying. And also, I think the notion that the thoughts were there first, and we had this great urge to be able to communicate our thoughts to other people. I mean, probably we worked out techniques for staying alive that didn't require language, but we had this urge that it would be a great benefit to us if we could, you know, make sounds that they meant something to us and more or less they meant the same thing to somebody else. You know, our relationship is proof of it. You know, I mean, we hit upon a simple phrase in one of our podcasts where we had already learned how to talk.

Jeffrey Madoff: There were several episodes where there was just no talking.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: Didn't seem to resonate with audiences as much.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Wasn't really worth doing next week. So we got it. But, you know, I think that thoughts are real. You know, I think that the fact that two people can share a thought and feel fairly confident that they're sharing the same thought means that thoughts are real and how they work. I'm not quite sure, but I do know that the greatest proof that thoughts are real is the punch line of a joke, where everybody gets it just like that. So they've obviously been in communication before the punchline. So that, bang, when the punchline comes, something has been almost uniformly understood by a large audience of people.

Jeffrey Madoff: But thoughts presuppose an intention. Thought is an intention. And I go back again to survival in the sense that that was the most basic intent was to survive, which I imagine very early on in evolution, it meant getting out of the way of danger.

Dan Sullivan: Well, and somebody dying, the person was alive and then they're dead, and that's a powerful thought. There's no disagreement. I think you had some evidence that there was no disagreement that they were alive and now they're dead.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I wonder how the first people, when someone was dead, when they were alive and then they were dead. I wonder what was made of that lifeless thing that was there. And I think the rituals, I was at a funeral yesterday, and funny thing happened on the way to the funeral. You know, we've ritualized death and lent it a significance way beyond that particular story's over. And then thoughts and memories are the intent to keep a certain idea alive about even though the person is gone, but I wonder way back when, how was death regarded? You know, all of a sudden somebody stops living, you know? And I don't know if people knew what to make of that initially. I mean, I've never thought of this before, but what'd they make of it?

Dan Sullivan: Well, and I think the other thing is, I just read a very interesting book called Same As Ever by a writer by the name of Morgan Housel, H-O-U-S-E-L. And it's 23 stories about different aspects of just living. And it said that we, well, we don't take into account of just how long people have been thinking about things. He said, you know, the number keeps being pushed backwards in time. You know, I can remember maybe 20, 25 years ago, they said that clearly these humans were human 200,000 years ago, and now they've pushed it back to about a half a million years, you know, like 500,000 years ago. And they keep finding signs of intention as far as tools go, intention as far as artwork goes. But we don't take into account, there's been continual conversations going on for 500,000 years about what does this mean? And that's a question, and people keep coming up with new answers about what it all means.

Jeffrey Madoff: And what does it mean to question something? What is the intent of a question? And how are we able to do that anyway?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I don't know.

Jeffrey Madoff: And again, I think that these mysteries, so to speak, always fell back on whether it was religion, whether it was a tribal ritual. I mean, how many times did somebody do a rain dance? And then when it rained, they associated that they had the power to cause it. And then the next task is to convince others that you have the power, you know, so that you can get into a particular privileged position as a result of that perceived power.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, if you just look at your own career, I'm looking at my career at the same time as saying, why have I become more successful? And I think basically because I've worked out capabilities that are, you can count on them. You can count on certain capabilities. I think what we're looking for is things you can count on in the future. You know, and I think of astronomy, you know, for one thing, cosmology rather. The Greek astronomer Ptolemy must have been Egyptian because there were pharaohs who were called Ptolemies, so it must be, you know, it was Mediterranean, probably.

And Ptolemy, if you followed his predictions today, they're almost just as accurate now as they were 2,000 years ago, even though he thought that the Earth was the center of the whole thing. But his predictions, because they had such a buildup of star formations and everything else, he was pretty good, you know. That's the hard thing about it is that his predictions, he could predict eclipses, he could predict all sorts of things when, you know, the star formations, you know, the ones that are Aries, Taurus, Gemini, they had worked out 12 major star formations. And when you got to that time in the year, you could predict this and you could predict that. I think we like prediction. That's the big thing, and prediction is very necessary for survival.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right, right. And where did Copernicus fall into this? Because you had to look through the telescope to even see those patterns.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, he just said that because some of the planets, they would go this way for a while, and then throughout the year, they would go this way. And he couldn't figure out how you could explain things, and so Ptolemy came up, well, there were epicycles, there were these vast formations, where Copernicus says, well, let's just put the sun in the middle, and it gets simplified. And that's basically how it happened. But if you had built your entire religious belief on the fact that the earth was the center, and somebody comes up and says, no, it's not the center, you're threatening, because not everybody's smart. I mean, we vary enormously in intelligence. And a lot of power comes with the belief that your intelligence is better than someone else's intelligence. And if someone comes up with a totally different description, it threatens your power. It threatens your predictive power.

Jeffrey Madoff: And, you know, you were talking about thought. I believe this is the first time I'm thinking about it, but thought is a luxury. If your entire being is about survival, you don't have time to think about much other than enhancing your survival. And so, thought about how to do that, thought about, you know, someone positioning themselves to be the ones that had the answers, or a figure that attribution was given to for having those answers. You know, it's fascinating because when you think about it, there are people nowadays in politics are called the elites. And I don't know how being educated became a bad term, but elites had the time to think about things where other people were more concerned about, how can I get through this day to the next?

Dan Sullivan: One of the things I found interesting that relates definitely while you're talking is why the United States shot ahead. I mean, it was already the greatest economy in the world in 1900. I mean, everybody says it happened as a result of the two wars, but actually, you know, the statistics that they have, economic output, productivity, profitability, and just sheer revenues. It was already true in 1900. And somebody went back and said, it has to do with calories. And he says, you're not creative if you don't have more than 2000 calories a day, because it just takes too much just to get the calories in that you don't have time to fool around with possibilities and new ways of doing things. You just don't have it.

And the U.S. from the beginning, except for during the Revolutionary War for about two years, they were really short on food during the Revolutionary War. But after that, the Americans always had enough to eat, more than enough to eat because they had such high protein available with wildlife and fish, you know, fish and animals, they could do this. And that's one of the reasons why you want to have lots of calories because it gives people time to actually sit back and ponder things.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, when you think about it, an awful lot of life for all of us is just maintenance. You know, now some have others to maintain things for them. And the further up the status ladder they are in terms of income or power or whatever, they're able to offload a lot of that maintenance to other people. But there's a huge swath of people that that's their day-to-day life getting from one day to the next and making sure that they have enough food in order to do so. And my guess is, as I'm talking about this, you could extrapolate way back in history to even the more primitive tribal aspects and that was still the case. And in understanding what's going on, I think it's about addressing challenges that people are facing. And how do you face those challenges or how do you position yourself that people believe that you are the one that can help them face those challenges successfully.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And, you know, there were smarter people and not so smart people. But they all tasted more or less the same when you ate them. I mean, cannibalism is far more widespread than people will admit to, you know. We're meaning-creating creatures. I mean, I wrote one of my quarterly books said, you are not a computer because the logic of there's a, what I think is a debatable proposition, and that is that computers are just information processing machines and humans are just information processing machines. I said, I don't think we're information processing machines. I think we're meaning making machines. We're not machines, and two, we don't, actually, we're not that good at information processing. You tell some information to another person, and they've altered the information the moment you tell them.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. That's right.

Dan Sullivan: You know, they have that telephone game. You have one person, there's 10 others. One person whispers in one ear, another person whispers in another ear. By the time you get to the tenth person, there's no resemblance of the first message, because we're not information processing. Meaning-making.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. And if my Aunt Ida was a part of that telephone game, I'd have to go to one other person to get corrupted.

Dan Sullivan: I'm not even good at processing information for myself.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, our memories are always changing. We are always unknowingly creating and recreating our own memories. We're changing the context. So here's the question that I have is, you know, there are things that computers are much better at. Computers can retrieve information faster. They can process meaning, pattern recognition, faster. And, you know, a shovel is much more effective than your hands in digging a hole. It doesn't mean a shovel is smarter. And I think that the most, and this may come out clumsy, it's the first time I'm thinking of this, we have intent. Humans have intent on their actions. And computers don't have intent, they have processing. Our intent is to get the answers from the computers. But what is intent? And do you think, two-part question for you, Dan. What is intent? And do you think a computer has intent?

Dan Sullivan: Well, I know what intent is for me. I have a picture, and it's a future picture, that if I do certain things, I'm going to get a different result than I've got the last time. I mean, I'm simply telling you the way I experienced it. It explains quite a big turning point in my life when I was divorced and bankrupt on the same day, which I've told you about, 1978. And I had this, first of all, when you go through those two experiences, people leave you alone. They don't, you know, they kind of give you a lot of privacy. And so I had about three or four months after that where I felt I was kind of in a really private part of my life, you know, that people didn't want to go out and have dinner with you because the subject of your divorce and bankruptcy might come up and they don't really want to talk about your divorce and bankruptcy. So I had a period of relative sort of peaceful quiet period of my life.

And what I came to is that how I handled what I had just gone through was going to basically determine the rest of my life. So I was 34 years old. And what I came to, Jeff, was the fact that I wasn't telling myself what I really wanted, both in personal relationship and economic activity. And so I said, what I gotta really get good at is telling myself what I want. So I gave myself a task of 25 years I would write in a journal, and every day in the journal I would write down something that I wanted. But no because—I just wanted it. I didn't want it because, I just wanted it. And after 25 years I became a really good wanter. And the way I experienced that is that you don't have to justify what you want. You just say that you want it, you know. It was really useful.

There's 9,131 days in 25 years, and except for 12 days, I wrote something. And I just got crystal clear, what do you want? You know, what do you want in this situation? Not, is it okay for you to want this? Not, what's your justification for wanting it? I just wanted it, okay? And so the big thing is how I experience wanting is I have a picture of myself performing at a higher level than I'm performing right now. So that's my explanation for what intending means.

Jeffrey Madoff: Was your intention, your intention, you're saying, was to define what you wanted?

Dan Sullivan: I was lacking a skill.

Jeffrey Madoff: And why would you say you're lacking a skill?

Dan Sullivan: Well, because the trouble I got into was, you know, both with marriage and bankruptcy, I wasn't telling myself what I actually wanted. I thought other people were going to tell me what I wanted.

Jeffrey Madoff: Okay, I'm not quite clear on that.

Dan Sullivan: Well, I was depending on my wife or I was depending on, you know, whoever I was connected with in business. Cause this was four years after I went entrepreneurial and I just wasn't giving myself clear pictures of what I was working towards. And so I said, I got to get good at this one capability. I'm just explaining that how I look at it, that I developed an incredible ability to be intentional.

Jeffrey Madoff: Intentional assumes that we're going for a certain outcome as a result of our action.

Dan Sullivan: And a measurable outcome. Money's a good one.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, it can be. Also, I think we both know enough people that no matter how much money they make, it still doesn't make any difference because they don't really know what they want.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I would say that's true. Or they think the getting of one thing is going to explain all the other things, and it's not true.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. And I think in business, that's oftentimes for people a wallop of a realization that that didn't make them happy. That didn't make them more desirable to be around, except when there were people hoping to get part of their bounty. That was really it. And by the way, we both have the luxury of being able to think about this, going back to what we've been talking about the past several minutes now, that our intent was to get beyond the basics, although we had never possibly articulated it that way. Because it is a luxury to be able to think about what you want or what you'd like to do or having choices when so many people don't.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: So I think that that's kind of fascinating in determining what you want. I think at different stages of life can also change. You don't necessarily want the same things. I think we're seeing an incredible explosion of people that want, let's call it extreme longevity, you know? And, oh, I do too, as long as I'm having fun, I wanna keep going.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Yeah. I have a firm strategy of not giving death any assistance. Yeah. So that's what I said. I think death is good at what it does. You know, I think I think it goes for low hanging fruit. You know, when death comes to me, it's too much work. It's too much work. Sullivan is just too much work to kill him. You know, so. I mean, it explains why we in our seventies and eighties are doing what we're doing. And the reason is because it's really interesting, you know, and interesting's worth living for.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, and to me, I use a different term, but I think we're saying the same thing, is I look for engagement. What involves me in a way that I find gratifying, enriching, fun, you know, all of those things that are important to me, my intent is to seek those out through activity and engaging with other people. And you have to be alive to do that.

Dan Sullivan: And I would say that for both of us, because we've, you know, we've been talking for a couple of years now, is that what my age is, is not a very, very important subject. In other words, I was interested the way I'm interested today when I was eight years old, now I'm 80, but it's more or less the same experience of being interested and engaged. I'll use your word because I think that's, it's more than just something you're doing with yourself, you're doing it with other people. You're engaged, and you're looking for skill level in other people, one that they understand what you're up. And it suits them, too, if you pick a project. When you first talked to us about your play, I had had a thought at one time earlier in my life where I'd like to be involved in plays, and I was. Not to the extent that I could make a living at it or would want to make a living at it. The reason Babs and I were so interested in your play is something that we could be engaged with.

Jeffrey Madoff: I mean, that to me has always been, you know, the biggest thing. I remember in school, the notion of daydreaming. I would oftentimes finish my assignments quite quickly and be sitting there and daydreaming was thought of as a bad thing. And I got good grades, that was never an issue. And daydreaming to me was thinking about other things that, you know, weren't what the teacher wanted me to be thinking about at that time.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, it was probably thinking about your thinking.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, yeah, well, you know, I mean, I would do things like, there was the old clock, so like click back and then a minute would go forward and you could see the second hand move. So I would try to hold my breath in between, all kinds of just games to amuse myself during that time. But, you know, the notion of want, and I think it's important to draw a distinction between what one wants and what one needs. And, you know, like somebody says, you know, I need a new coat. Most of the people that say that probably have a few coats in the closet. Why do you need a new one? Why do you want, you don't need a new one, you want a new one. What separates a want from a need? Can I explain it?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Your wanting is true and the because is fiction.

Jeffrey Madoff: Okay, take that a little deeper for me.

Dan Sullivan: Well, I'll give you an example. What I've noticed since I've been coaching entrepreneurs for 50 years, that so far as I've experienced that male entrepreneurs are bigger wanters than female wanters. Part of the reason is because it's been fairly recent in history that women could just go into the marketplace and create a business, where males have been doing it one way or another forever. And what I noticed was, and I've come to grips with this because when you look at our top level, which is called Free Zone, at the bottom level, about 25 to 30% of our entrepreneurs are women. And you have to be making 200,000 personal income for you to qualify for the bottom level. And at the top level, you're so far beyond that it's not even meaningful, most of them are in the millions, they're making millions of dollars.

And what I notice is it's easier for males to talk male entrepreneurs. And I think this is strictly a function of history and it being okay just to go out into the marketplace and do well. And it comes up around the question, how much is enough? So for example, for me, I'm not doing it to answer any question enough. I'm doing it because it's the next thing I'm going to do. But I've noticed that female entrepreneurs are challenged to say why they need to get more. And they'll come up with a story like, well, I gotta make sure my kids have all the money they need for education. Okay, but they always have a practical reason why they keep going, except for the really top ones.

And we have top ones in the, what we call the Free Zone. And they're doing it just out of sheer engagement. It's the next level beyond where they are, and that sort of excites them. But they don't have any practical reason for making more money. It's a scorecard that if I'm doing more money, it means my capabilities have jumped. You know, and I'm able to do this now, and I'm able to do that. And I think that your intentions or your goals at a certain point, it's a more fun game ahead. If I can jump to the next level, it's a more fun game. And I think women are just learning this.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, but I think that I agree with you, money can be that scorecard. But there's other things that can be that scorecard. And I would like to think for myself that, and again, I'm speaking from a position that I have some money. I'm not in survival mode. And I think it's important because again, there are people that that's their day-to-day thing is just getting by. Those who are more fortunate and don't have that challenge, I think there is something about whether it's passing knowledge on, whether it's engaging with others, whether it's doing things that gratify one. And I think if one's only gratification comes through increasing their money scorecard, and I've met people like that, many people like that, I don't find that so interesting.

There's nothing less interesting to me than somebody telling me about the deal they did, you know, and as over the last couple of years as you and I have been doing this together and so on, money has never been the primary focus of what we're talking about. You know, the engagement that you get from what you're doing at Strategic Coach, the engagement comes from the quality of the interactions or the effects that you have on these people and what they do. It doesn't come from the fact that they pay you really well affords you the opportunity to concentrate on that stuff. But I suspect no matter what you would be doing, a lot of it would be cerebral.

Dan Sullivan: Well, the big thing, I talk about the Four Freedoms that, you know, people who aren't entrepreneurs, when they talk about entrepreneurs generally zeroing on the money, they say all they care about is money. And I said, well, it's a reality. It's like the law of gravity. I mean, money is really interesting because what you really want to do is buy time. So I said, the first freedom that you want is freedom of time. And the way we've arranged things in Strategic Coach is that if you just look at what is really crucial for you to be doing in your own company, and you get rid of the things that somebody else can do, then you can buy back time.

And with you freeing up as the central entrepreneur, I'm the number one entrepreneur in the company from the standpoint of money-making. And so I can buy back time. Every time I buy back time, the amount of money for the company keeps going up. And then with time and money, you can then be very choosy about the relationships, external relationships and internal relationships. More and more, the first three freedoms actually buy you purpose. I think purpose is a result, I don't think it's a cause. I think purpose is created out of greater and greater freedom of money, time, and relationship. What you're doing and who you're doing with it gets more and more interesting as you go along.

Jeffrey Madoff: So this is an interesting fertile area that you're coming to. Have you ever had, you don't certainly have to name names, but have you ever had people that their desire, their unbridled desire to make more money, and that's what they're interested in, period. How can you help me make more money? Have you ever had clients at Coach that you ultimately found their goals or their metrics or whatever counter to, I don't even know how to phrase this, that you didn't want them as clients because what they were striving for somehow turned you off or you didn't feel that you wanted to deliver because that's just not the kind of person you were interested in?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, yeah. And I would say it happened so quickly that we go separate ways now, but in the early days, you know, I mean, first of all, I needed cash flow. Yeah, yeah, I needed cash flow, but to the degree that I didn't need this particular relationship for cash reasons, then it just didn't happen. You know, I can think of, not many recently. And part of the reason is they get screened out because they're with other coaches and they're lower in the level. So one of the benefits of being in the just coaching the top level in Coach is that they didn't make it that far. It wasn't unsatisfying to them to be in the Program because we were asking all sorts of questions.

How is your relationships with your team? How are your relationships in your personal life? And how are you being useful? And they said, I'm just here for the money. And I said, you're not gonna be happy here. And we're not gonna be happy with you. Yeah, I had one guy, he's from Long Island, and he said, I only want to be with you. You know, if I come into the Program, you know, he hadn't been in Coach. He said, but I'm not going to come into the Program except if you're the coach. And I said, well, that clarifies things really fast. You're not going to be with me. And I said, you have to go through levels. He said, look, I'm already making five million here. And I said, big deal. What's that mean? And he says, well, I'm not gonna be in a, are all the people with you? I said, I have no idea how much money they make. I know it's enough. That's not the game they're playing. They're not playing that game. It's the wrong game for you.

Jeffrey Madoff: So, I mean, I have had the same thing where there was just, it was a relationship I didn't want. And that's actually been fairly consistent throughout my life, even, I was able to shut myself up, even when I needed that money, because it was just, I found money you can get back, time you can't.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, what you're creating there is standards, you're creating standards.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right, yes.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, you're establishing a standard for yourself and you're willing to take a risk to establish your standard. Yeah, I talk about those people. They know the price of everything and the value of nothing. Yeah, well put.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. What is, I like this a lot, what is the establishing a standard?

Dan Sullivan: Well, first of all, I think it's, I mean, I've been thinking about this a lot lately, and more and more, I think the greatest contribution that you can make to another person is your standards. Okay, and that is, I will only do certain things that have a certain quality to them, and if I can't guarantee the quality, I'm not interested in the activity. You know, and you've talked to, you've given many examples to me over the, like when you're fundraising for Personality and the person says, you know, yeah, well, you know, if I don't remember the exact conversation, but it was along the line, you know, if I'm going to give you this amount of money, then I'm going to have some say about the play. And you said, no, you're not. You're not. I said, I need money, but I don't need your money. And I think standards are the thing that you can really make permanent in your life.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and this producer that I met and wanted to get involved with the play.

Dan Sullivan: And he had pictures of himself with everybody on the wall.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, that one. That was actually a lawyer, an entertainment lawyer who somehow thought the currency of him having a picture taken with a celebrity bought him entree into any doorway he wanted to go through.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, yeah. Sometimes I think there's a real tension between the word lawyer and entertainment.

Jeffrey Madoff: Perry Mason was very entertaining. It was very entertaining.

Dan Sullivan: I remember the lawyers on Law & Order were very entertaining.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. I always try to imagine this is a real that now we're going into our Anything and Everything world, but it reminded me like my grandmother loved Perry Mason. You know, we watched Perry Mason. And then when Raymond Burr, you know, when that series ended and he had become very wealthy as a result of that.

Dan Sullivan: A wealthy Canadian.

Jeffrey Madoff: Was he Canadian?

Dan Sullivan: Raymond Burr, yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: So anyhow, I was trying to imagine his negotiation when they wanted him to do Ironsides, playing another lawyer, but who was in a wheelchair. In Perry Mason, he had gotten heavier and heavier. So when he was giving his closing arguments, he'd always be leaning against the wall of the jury or holding onto the table. And I'm thinking of those negotiations, and he's probably saying, I'll do it, but I'm not going to walk. I'm not gonna walk. Well, what do you mean you're not gonna walk? I'm not gonna walk. You gotta move around the courtroom. Put me in a wheelchair. I'm not walking. And I always got a huge kick out of imagining negotiations that his agent had with the network about him playing a lawyer and the way he wanted to differentiate that lawyer is he did not want to have to move around anymore. It got him too heavy.

Dan Sullivan: I think that happened with Orson Welles as he went on too.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh yeah, yeah. He got really big.

Dan Sullivan: Yes, he did. Really big at the end, yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, that's because he would drink no wine before it's time. But the thing that you mentioned about standards is very interesting to me because I think standards are so important. And this producer that I was working with early on in our meetings, he said, and this is kind of the same thing, he said to me, look, I know what you're gonna do is going to be good because you have good taste. And I had never heard it put that way before. And I said, what do you mean? He said, well, you have standards. You're not going to go below what your standards are. And that to me is more bracing than anything else.

And, you know, I didn't give up doing everything else to focus on the play and our book and what we're doing, you know, that those to then have to compromise what my standards are, you know, that's not what I wanted to do. And so that person who wanted those controls over it, I'm the wrong investment for them. You know, ‘cause I would not compromise my standards. And I did this so that, you know, I had spent 40 some years working with clients who were wonderful. And I, it was a very good run with people like Ralph Lauren and Victoria's Secret and Tiffany and Harvard and all of that.

But this time I was choosing all the questions I wanted to answer, the stories that I wanted to tell, the team that I wanted to put together and the standards, which, I think it's an interesting word because I don't know if it's as much a function of getting older as it is just having more experience. Maybe those go hand in hand, you have more experience because you're older. But to me, in so many realms, standards have so fallen. And I find that even with, you know, we're renovating our apartment. We have Margaret, my wife and I really love mission style furniture.

Dan Sullivan: We love it too.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. And so I was talking to this designer because we need, you know, we need to, it's been bleached by the sun. It's got to be all reupholstered, all that. That's quite costly. And I was thinking of, you know, well, so maybe we'll look and see if there's anything we like better for the cost that it would cost us to do that. And we couldn't find anything we liked better or that was as interesting. And I was told by a few people, one of them being the designer, was, you know, that stuff that you have, it's not made like that anymore. It's not made as well. You know, this stuff is like solid. I mean, it's bleached by the sun because your apartment gets so much light. But, you know, you're not going to find things as well made. And I think in so many areas, that's true. And I think that standards in so many areas of life have changed. I don't know, standards are a very interesting metric, because I wonder if people could articulate what their standards are.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I think one of the things that I found that when I first started coaching, I experimented. I mean, I had entrepreneurs right from the beginning, but I experimented with corporate people. People were in corporations. And I experimented with people who were in bureaucratic organizations, government bureaucratic organizations. And I found that after I'd had enough experience, I said, I'm only gonna go with one kind of person, and that's an entrepreneur, but they have to have a future. What I realized is that from a practical standpoint, entrepreneurs were the only one that could make a decision on the spot and write a check on the spot.

If it was corporate, they'd have to, first of all, they didn't wanna pay for it themselves, they wanted the corporation to pay for it, which was a minus as far as I was concerned. And it was even worse with the bureaucrats who were in government. You know, they'd have to get approval. They'd have to do this. And, you know, it got very, very complicated. But the entrepreneurs, they said, when can I start? And I says, you got this date. And he says, good. How much up front? And I said, this much up front. But I think that entrepreneurs, by their very nature, have a greater opportunity to live their lives by standards than people who, it depends on somebody else's decision.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, because you have to hew those pre-existing standards, which isn't necessarily a bad thing.

Dan Sullivan: No, I think it's a good thing. I think it's a good thing. I'm not saying that they're dishonest or anything. They have less control over their future. And entrepreneurs, if they have the intention of having control over the circumstances of their future, and they're actually talented and they actually create value, they can pretty well establish standards for their, yeah. Yeah, so I met a very interesting guy. He's from New York City and he's in the hospitality business and he just started the Program. I was in our headquarters over the last week and I was having lunch and he sat down and he's a great admirer and sort of student of Danny Meyer from restaurant tour.

I found his partners with him in Siciamo, Hillary Siciamo. And he said the biggest thing that he got from them is that you never treat your customers better than your team. And he said, never have a difference between how you treat, because your team members are your outer face with the marketplace. So he says the way, the kind of client you wanna have, you have to treat your team members that way right from the beginning. And I said, that's killer. I love that one. Oh, absolutely. I love that. That's a killing concept.

Jeffrey Madoff: And to me, that's no different than when I would go out to dinner with a potential client, and I saw either how nicely or how poorly they treated waitstaff. And that would be, that would just be a turn off to me when people would be either rude, not even acknowledge somebody, whatever it was, and I could tell this person and I aren't gonna get along, and I don't wanna do this, unless it was a lot of money for a very short time. Then I would have done it.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, we all have, yeah. But the longer you can go sticking to your standards, the better it is. Yeah, yeah. I mean, it's a risk. I mean, it takes courage to do that.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, that's, as I've probably stated before, that's my no asshole rule, which is that if you are paying me, you can never be abusive. I won't tolerate it. You can be an asshole if you're paying me enough, but if I'm paying you, you can't be. And it's pretty simple. But you hit on something that I think is very worth repeating here and going into a little bit. And that is when you were deciding, and I don't know if it was conscious or it just happened as a result of, you know, you had took whatever meeting you could to see who would be a client and eventually, you landed on entrepreneurs. So number one, it's knowing who your market is. But my guess is that the reason that that was your market, the entrepreneurs, is it was the least amount of friction to get to a yes. Is that accurate?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, yeah, very definitely. Well, and the other thing is, we were akin in how we were making our living. Corporate people are interesting. You can work with corporate people if you realize that their company is their career. One way of really detecting that early, they want you as a secret capability. So if you got examples I can think of where it's been very successful with our clients with a corporate person is that the corporate person has a company that's called their career. And it's not specific to the corporation that they're in. It may be short term, and CEOs, the average is six years. If you take the Fortune 500 corporations, it's very seldom that a career in a corporation for a CEO is more than six years.

And what they're doing is they're building up their capabilities, because at a certain point, they're going to do a jump to another core, especially public corporations. And as long as you realize that, because when you're really useful to them and they succeed in building their career, they won't tell anybody in the corporation about you. You're theirs. I mean, you have to look at your own experience there, but how many of the people that you had long term relationships with is because it was a one-on relationship between you and them? It wasn't a relationship between you and the corporation.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. My longevity with Ralph Lauren is a very good example of that.

Dan Sullivan: And that was not okay with some of the people in that company.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, I was highly resented by those. And it's interesting, and I hadn't thought of this before either, is that Ralph was an entrepreneur. He started the company. And my parents, were entrepreneurs, you know, they started their retail businesses. And I initially, and I think part of this was just naivete, that when I would get hired, I always treated the person that hired me as if they owned the business, because that's what I was used to with, you know, my parents. And it wasn't until I gained more experience and realized what you put very well, which is that there are those that work within corporations that you know, that you look at the company as their career, but it's agnostic. It's whatever company moves them forward in the direction they wanna go.

Dan Sullivan: So in a sense—and I totally get that. It's not something that I personally would be capable of, but I totally understand what they're up to.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes, I do too. And I often wondered, because I saw this in some major, major public companies that, to get rid of that person. In the first meeting, I could tell, God, this person's gonna be a disaster here. And they paid them millions. In one case, 27 million. They get rid of them. How do these people fail upwards so often? Because the company doesn't wanna admit they made a mistake, and there's all the non-disclosure and confidentiality agreements that go along with it. And so then the story that gets made up is, you know, wanted to spend more time with their family.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, sure. I believe that.

Jeffrey Madoff: And they're paid a fortune and they have a resume that if you just look at the names, seems impressive. And then when they land their next job, the people who screen them can say, well, look at who they've worked for. And it's all a fiction. They've wrecked so many different companies or wreaked so much havoc that it was worth paying them a ton of money just to get rid of them. But it's never addressed. And I always find that, you know, how do I fuck things up and get paid 25 million? How do you do that? Well, I think there's a skill involved.

Dan Sullivan: Yes. But the thing that we're developing, I think standards are a certainty of how you're going to be in the future, regardless of what the circumstances are. And that's why standards. It's not that you're predicting the future, you're just predicting how you're going to be regardless of what the future is. So I think that's why standards are so important.

Jeffrey Madoff: And I think that's why there are people that in any field, when we go into Personality, my play, there are people that wanna work with Sheldon Epps, actors who know him, who have worked with him because of his standards, because of people who have good standards in whatever world they're dealing in, whether it be a business or creative or whatever, that they think they're going to learn something, or they've had experience and want to work with that person. And again, it all funnels down to relationships. and relationships that you establish.

It wasn't a calculation on my part, because I could have never made the calculation that what I have to do is get Ralph to like me, Ralph Warren to like me, and then I'm safe. Ralph and I got along. It was a true organic situation. And it had nothing to do with me trying to somehow calculate how I can get into his good graces, because I'm very bad at doing that. Because that's a performance I'm not willing to give. Then you gotta sort of remember who that character was. You know, I'm just, what lie did I tell you?

So it was interesting, and I think the fact that he was an entrepreneur made it even, underscored the fact that the relationship, which I believe in all cases, but that the relationship was the most important thing, you know, fall on the sword for the relationship, not for the deal, because that's going to screw you. And so it's fascinating when you get into that realm, because then there's kind of a deep psychology going on here about understanding what motivates somebody, what are their standards. I love the way you put it, because you can look at what that person has done, and that's a predictor of what they will do.

Dan Sullivan: And even at a sacrifice, they'll do it.

Jeffrey Madoff: I'm sorry, say that again?

Dan Sullivan: Even at a sacrifice, they'll do it. That's the important thing, that they'll bet on themselves for the future. Regardless of what the circumstances are.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. Yeah, it's fascinating. And I can say that with Ralph, I saw that in action. And because I was involved in so many different areas of his business, I saw that across the board. There was never a, there was never a sacrifice. He always protected what he did. There was a time when I was doing this film for him where his head of corporate communications was in there. It was a fairly, you know, the upper of the upper-level people were there whose opinions he trusted. And their head of communications was relatively new. And you always have to be careful of relatively new people because they're going to try to establish their perimeter and protect it, which I understand.

And when the film finished, Ralph said, okay, you got me. You know how to get me. You got me. I'm crying. This worked. This worked. We wanted people sitting there like that and all of that. Then it comes to this person. And so this was an opportunity to try to make her bones. And she said, it wasn't emotional. And Ralph loves things that are emotional. He loves things that are emotional. And she said, didn't work for me. And I said, Ralph is crying. He is touching his heart. She is crying. Everybody in here is but you. Okay, so you don't often get 100% of the audience on your side, but I got all the ones that are important. And you're just trying to make points. I'm not changing it. And she got into a huff and Ralph actually stood up and said, well, calm down. Everybody needs to calm down.

Then he said, come with me. And I went with him and he said, I'll drive you back to your office. And I said to him, how can she say that? This is an emotion when you're crying all that. And he said, I like what you did because you're protecting your work. And when you're protecting your work, you're protecting me. I want you to know I understand that. And I said, that means a great deal to me. Thank you. But when you get into these companies and the politics, which can be hideous, the fact that I had a relationship with Ralph was paramount.

And so those relationships, you know, mean a lot. And it's important to nurture those. And I think throughout life and different aspects of life, because I think you can apply that metric of standards to everything. What kind of relationships does this person have? And then going back to what you were saying, how some people reveal themselves really early on as not being the kind of client you want or not being the kind of friend you want.

Dan Sullivan: The one thing that I've really developed a nose for who's an entrepreneur that the whole game is about constant growth, you know, as opposed to a status entrepreneur that they have, you know, I use Akron as an example, you know, you're born in modest circumstances in Akron, but there's better places to live in Akron, you know, than other places to live. So there's certain anybody having to do with rubber industry lives in a house that's probably really great, you know, the original, the good riches, the good years, everybody. So you want to have a house in that neighborhood, and you want your kids to go to this school, and you want to belong to this club. And that's your standard of who you're going to be in the future.

So the big thing that I've really detected very quickly is the people who, regardless of their age, their greatest motivation is the next growth stage where they're going to be learning something new, developing new capabilities, surrounded themselves with a stronger team, and there's no end to it. I'm more ambitious at 80 than I was at 60. One is because I've got, I realize it's all through teamwork now. It's not me, I'm good enough. I'm good enough. I don't need to, but I have to get better at teamwork at all times.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I mean, I think for me, it's always, you know, I had a tendency, I think, when I was younger, that if I liked somebody, I hoped that they could develop the capability. And sometimes that was true, other times it wasn't. But I learned pretty quickly, because again, that's a survival thing of when somebody was just over their head. And even though they wanted that opportunity, they couldn't ascend to that level. They weren't there. Because again, it all goes back for me to relationships. and how I value those, but I also have to be realistic about how some things can play out. And I get that too. But I think that one of my capabilities is putting together really good teams. The casting not hiring aspect of what I do, which is important to me. I think we got into unexpected and interesting areas.

Dan Sullivan: I mean, what was all started on the big questions. Well, the big question is, you know, I have a team and you've met a number of the team members that at a certain point I'll sit down with them and I'll say, I want to give you this as a compliment, that when we're not working together, I'm not thinking about you. Because I know that you're doing good work. I know you're doing great work. Whatever challenges you have, I know that you're going to rise to the challenge. So I want you to take this as a compliment. When I'm not actually involved with you, I'm not thinking about you.

Jeffrey Madoff: And they understand that. And for me today, there was a lot of thinking about the thinking. What are those big questions? What are those freedoms that we are after and standards? What are those? And are you aware of your own standards? Because that's part of the that can be both predictive in terms of behavior, and that prediction has a pretty good chance of being true if that person is consistent, because to me, inconsistency is not a standard that I can hew to.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, but you can't bet on it, that's the problem.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right, that's right. And is it really a standard if it's not consistent?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, that's good. And, you know, back to casting not hiring, I think why roles are superior to jobs. A job doesn't tell you anything about the predictability of the person. A person filling a unique role, it tells you a lot. And you're setting things up so that they can be more and more unique. I think that's the thing, is that they can grow within their uniqueness. So what do you think?

Jeffrey Madoff: Did this fit under the umbrella of anything and everything?

Dan Sullivan: I think so, yeah. I was looking for weaknesses, but it seemed to be strong all the way through. But, you know, going back to the survival aspect, I mean, what kind of life do you have where you can't make predictions about other people's standards? It's a really, it's a nerve-wracking life.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, and the funny thing is, is when you can't predict other people's standards, you can't predict their behavior. Yeah, which is the foundation of a lot of good drama.

Dan Sullivan: I have in the Program a number of people who were Navy SEALs for, you know, at least 10 years, they were Navy SEALs. And that hell week that they go through, that one week that they go through, you know, which in a week, they might get 10 hours sleep in seven days. And they're just confronted with physical challenge after physical challenge. And they said that the reason why they do that is that the chances are they'll never have a worse week than that in the future. Okay. And in the future, they'll be depending upon a team, but in the hell week, they have to depend totally on themselves. If they make it through in about, I think they start with 80 or 90. And I think they end up with about 10 or 15 who make it through the entire week. And they said that everybody has to know that this person is totally dependable. You can't think about it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right.

Dan Sullivan: Right. Yeah. Anyway, it was great. I think it relates very much to what we're talking about, why the roles are so important.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and I think that over these last couple of years we've been doing that, we've established some standards.

Dan Sullivan: Yep.

Jeffrey Madoff: And mainly the standard is go wherever you can and engage however much you can to convey, to convey what? I think the intent is just, for me, the intent of all of our discussions so far has just been discovery of where we're going because we don't set up the destination from the beginning.

Dan Sullivan: Like Star Trek. Explore new worlds.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think we did that today.

Dan Sullivan: That was great. This was really great.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. Should we give our sign off?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Put it in your calendar. At the end of this year, there's going to be a great new book called Casting Not Hiring. We're going through the process now of you know, getting first class spectacular copy. And this is going to be something that entrepreneurs throughout the world are going to absolutely love this book. They're going to buy large quantities and give them to all their friends. And it's going to change the way that they conduct their business for the rest of their life.

Jeffrey Madoff: I could not put that any better. And I think that it is a great gift for everyone, you know, or will ever meet in your life. Thanks for joining us today on our show, Anything and Everything. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend. For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

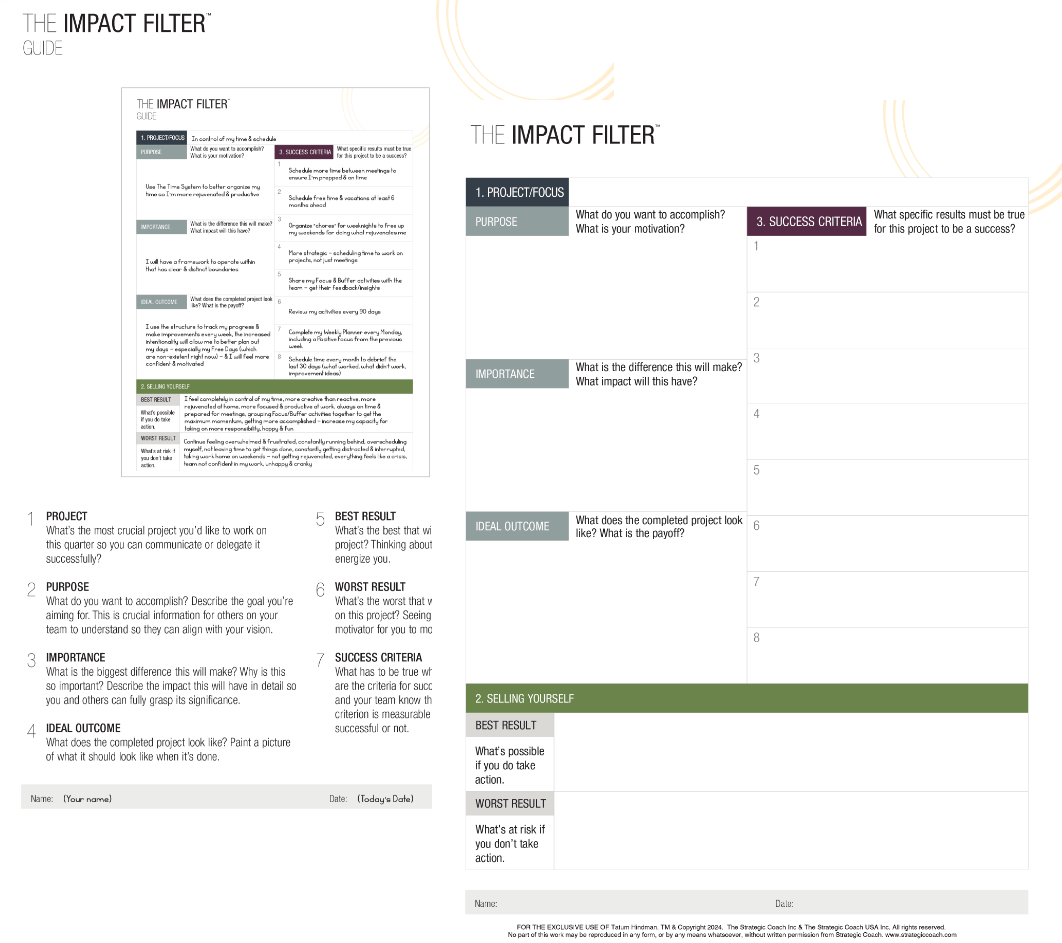

The Impact Filter

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter™ is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.