The Fusion Of Ambition And Passion In Entrepreneurship

May 06, 2025

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

Do you chase external success or internal fulfillment? Jeffrey Madoff and Dan Sullivan discuss ambition versus passion—how they differ, intersect, and fuel entrepreneurs. Learn why passion sustains long-term commitment while ambition alone falls short, and discover how to combine them for lasting impact.

Show Notes:

Passion is your internal drive, while ambition translates that drive into measurable success.

Ambition without passion burns out because external milestones like money and fame hollow out without the joy of the process.

Passion is what fuels long-term commitment because it’s what you can’t not do.

True passion creates freedom—doing what you want, when you want, with whom you want.

Childhood clues reveal your passion. What lit you up as a kid often points to your lifelong strengths.

Great entrepreneurs fuse principle (passion) with strategy (ambition).

Retirement is the enemy of passion.

Getting people to talk about their experiences is a great way to learn a lot about the world.

If you ask people questions that connect their experiences, they get very excited.

Resources:

Everything Is Created Backward by Dan Sullivan

How to Win Friends & Influence People by Dale Carnegie

The Power of Positive Thinking by Dr. Norman Vincent Peale

Casting Not Hiring by Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff

Learn more about Jeffrey Madoff

Dan Sullivan and Strategic Coach®

Episode Transcript

Jeffrey Madoff: This is Jeffrey Madoff, and welcome to our podcast called Anything and Everything with my partner, Dan Sullivan. One of the questions I was asking myself before our call, because you always cause me to self-reflect before we get on the call, is the notion of ambition and passion. And with my play, Personality, people often say to me, well, is this a passion project, you know, or is this a commercial project? And my answer is yes. You know, it's both. And I wanna talk about ambition, passion, where do they cross over, where are they different, and how did that all come about? So I'd like to start, Dan, by asking for your definition of ambition.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I see it in sort of operational form. I think passion is an internal thing. I think it's like an engine, you know, and that is, it's that which you cannot not do, you know, that you have a drive, internal drive, the way your mind works, the activities that you involve yourself in. And we've talked about it on previous podcasts, but I'm very, very passionate about how people see their experience and how they've come to grips with their experience. When I was young, I was fascinated with adults' experiences. And when I was, you know, very young, eight years old, let's pick that as a number, grew up in circumstances, farm country, where I didn't have other children in my life, neighbors, you know, but quite a distance from school. So you had to drive in in the morning and you had to ride home. There was no later in the day, after school, hanging out with other children.

But there were lots of adults around, just in terms of the farms, you know, next-door neighbors' farms, and all the businesses that were involved with farming, the centers where the tractors and the equipment came from, and then there was the markets where the produce was sold. So I got to go along with my father, mostly, and my mother, too. And I like to talk, and I like to listen. And so, I don't know when the idea came into me that if I could just get the adults to talk about their experience, I would learn a lot about the world.

From a history standpoint, I'm very passionate about history. So, you know, I knew people who were born in the 1870s, people who were born right at the start of the century. But their ideas almost appeared as diagrams in my brain. Okay, so I would see them talking and I could see it as arrows and stars and boxes and everything else. And I could ask them how things connected as far as their experience. And one of the things I noticed, they hadn't made the connections in their experiences. And if I asked them questions about the connections, they got very, very excited. Well, guess what? 70 years later, this is how I'm making my living. So you can say that asking people questions that got them to connect their experiences was a passion on my part.

But it wasn't a business, you know, it was just an activity. But I also, from farming being an entrepreneurial activity, and none of my siblings, I have six siblings, none of them found how my father made a living in the whole business of the farm. I was really, really interested, how do you control your time like that? Like most of the children, when I finally did get to school, their father worked for somebody. My father worked for himself. And that made a deep impression on me that somehow this thing I love to do, I had to find a way that I could get paid for it. Okay, so I would call my passion was other people's experience.

And the fact that if I asked them the right questions, they got very excited about their history. They got very excited about what they were doing 50 years ago connected with what they were doing today. I got very, very passionate about that. But how do you make a living doing that? And it took me ‘till age 30 before I figured that out. And then my ambition, of course, was to make a full living doing that. And I call that my ambition. My ambition was to make a certain amount of money and have more and more of my time to myself just to exercise my passion. So the ambition is how your passion connects with the world. Okay, and that does your passion that has such a big impact on you, if you express it right, if you utilize it correctly, can you get paid for that? So that's how I see the relationship between passion and ambition.

Jeffrey Madoff: It's really interesting because both of them are the product of a strong desire to do something. One of the questions I ask my guests in class, and I always start off asking this question, which relates directly to what you were talking about, is what is it you did when you were a kid that really lit you up, that you really like? Because I believe that if you can figure out, like you did, like I did, a way to make a living doing what I really love doing, that that's a very worthwhile achievement. And, you know, both of us did that not through getting a job, but through creating a business. You know, the entrepreneurship aspect of it, which I think is really interesting.

But I also like looking at the etymology. What are the word roots? Where do these things come from? And ambition, ambition came originally from the act of canvassing for votes in ancient Rome. And over time, it came to mean eager and inordinate desire for honor or preferment, which I think is really fascinating. But it is also interesting because in early English usage, ambition often carried a negative connotation, association with pride and being vainglorious. So that bridges into then passion and where passion comes from. And I'm curious, how did you experience these adults experiencing their life through the questions you asked?

Dan Sullivan: Well, I believe you can have anything going on that you want inside of you, but you don't know whether it's real in the world. The only way you know in the world is that it … and you have to do a translation, you know. You're not telling, well, I've got this going on inside me because, you know, and I think you should be interested in that, you know. Then I think the third, if there's a Triple Play here, I had the passion, I had the activity I love doing, I had the ambition to be freed up to do this money-wise, time-wise. And the third one was I found that questions was a really, really useful speech capability that you could talk to people and you could ask questions. And if the question was about them and about the experience that they had, and then you just ask them to connect the two, well, you did this.

And now that you look back, you know, when the industrialization of the farm happened, for example, I was meeting grandparents, you know, of people who were adults, their grandparents were still alive, and they had been farmers. And then the children, who are now adult children, were the businesses that were supplying farmers. And that if you could not make it about you, but you could play the game of it being strictly about them and their experience—another skill that I learned, don't make it self-referential, you know, it's about them. You're just describing a game that you see, that they'll give you enormous amount of attention, you know, they'll be fully there because you're talking about them.

The other thing, Jeff, that I noticed along the way, that what I was offering them was a very rare experience. Okay, that not, you know, I remember very early, not at eight years old, but probably in my teens or late teens, that if you could get people to talk about their experience and give them your wholehearted attention, nobody else had ever done that to them in their life. Giving full attention, you know. And I wasn't trying to get anything out of it. I was just seeing how, I wonder how far I can keep this conversation going. You know, there were rewards to it. You know, you got treats, you know, milk, cookies, other things like that. But they took you seriously. They took you really seriously.

I remember I had a high school principal who had been in the service before he went into the priesthood, Catholic schools. And my mother, whenever there was a big event like an election, I got to stay up late for the election. I remember that was ‘52 was Eisenhower, Eisenhower won. So, you know, we stayed up late and didn't go to school the next day. So my mother wrote a note. Your parent had to write you a note if you were absent. And I came and I still got a penalty for it. And my principal, said, well, yeah, staying up late and watching election is education, and we also have education here, and this is the education you have to get. So you go to penalty period. And I took it well. I said, okay, I'll do the penalty.

And then for some reason, my taking it well, and my mother didn't push back at all. She said, well, it was a choice, and we made the choice. So there was no pushback from the parent. So we got talking, he was in the Marine Corps. Okay, so this is in the fifties, so he would have been Second World War. So I got really interested in asking him all the questions about, you know, about the war and where it was and then what gave him the idea of going into the priesthood afterwards. And for him, it was the structure that he really loved, the structure of the Marine Corps. And he loved the structure of the church. I said, well, what's the difference between the two? And he says, the one of them comes to an end and the other one doesn't.

But I could see he hadn't made the connection before I asked him the question. And that's a win for me when somebody makes a connection between the two of their experiences, and it was my asking the question. That's a real reward for me. That's a visceral reward that I get. And, you know, I would talk to him. And, of course, he had his eyes on me for the priesthood because he was a recruiter too, you know, and I wasn't going in that direction. So when we got to my twelfth year, so this would be ‘61, he said, you know, we talked about college and there was no money for college. And he said, well, I think I can get you a job if you'd be interested in after high school.

And his brother was the agent in charge, the FBI agent in charge in Cleveland, our nearest city. And he said, and he's got leeway, you know, in his job that he can actually, several, FBI is not civil service. They had their own system. J. Edgar Hoover, you know, had his own system. And so he said, would you be interested in that, you know? And so he drove me into Cleveland one day. I met his brother-in-law and I got myself a job in Washington, D.C. And that was JFK. JFK was the president. And his brother was the attorney general, which the FBI comes under the attorney general. So this is terrific. You know, I got, none of the other kids would work, you know, they'd leave school and they'd go to GM or they'd go to Chrysler, you know, they'd work on the line. And here I was in the nation's capital. And I knew it was my questioning that got me that job.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, you had a certain reward structure that was built into it. You know, not only did you get attention, you got treats.

Dan Sullivan: And special treatment.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, as it goes, the preferment. Preferment. Yeah, that's interesting. What do you think fuels ambition? Is it competition? Is it achieving milestones or goals? What do you think fuels it?

Dan Sullivan: Well, they're sort of like a scoreboard. It's kind of like a scoreboard of how well you're doing. And I think that money is a way of keeping score. Getting opportunities is a way of keeping score. And of course, getting special treatment itself is keeping score. And I don't remember if that had any impact whatsoever on the children around me whatsoever. I know I never did it with them because they didn't know anything. That was the biggest thing I noticed about children my own age. They didn't have any experiences worth talking about.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, that's an interesting take, you know, because I found, well, it depends, you know, certainly with my own kids, I found how they experienced the world quite fascinating. One of the things that Margaret, my wife, did, which was really interesting, Audrey was always incredibly verbal at a very young age. And Margaret would audio record their room at night. And it was like a verbal hieroglyphics. And you could begin to trace the beginnings of certain words, which were, it was just kind of fascinating. And I was very happy that Margaret would not have.

Dan Sullivan: How old was Audrey at that time?

Jeffrey Madoff: Little over a year.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, wow.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. I mean, she was talking early, very early. Yeah. And so I thought that was that was really that was really interesting. Also, she's a twin.

Dan Sullivan: But is she number one?

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes. That's right. Jake, her brother, and girls are generally verbal before.

Dan Sullivan: That’s right. They have to be.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, yeah, that is also true. But it's really fascinating because going back to the word origins again, with passion, that didn't come into English ‘till like the 13th century. And passion, and I found this fascinating, is it initially referred to the sufferings of Christ on the cross. And suffering, enduring, and martyrdom is where that came from. I thought it was really interesting because we often think in terms of the arts and the tropes that are in books and movies and plays is that, you know, you suffer for your art, which I never believed. I try to avoid suffering whenever I can. I see no virtue in suffering. And I wondered, so where's that?

Dan Sullivan: And that includes fools. You don't suffer fools.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's the worst suffering.

Dan Sullivan: That is the worst suffering. That actually is suffering.

Jeffrey Madoff: But you know, it's kind of what you're talking about, and I think this also applies directly to entrepreneurs, which is that passion refers to an interest or passion that's so deep that you're willing to invest time, energy, and effort to develop it despite all the challenges and difficulties. And at the top of the list is not money. As you were saying, it's, they can't not do it. Which I think is really, really interesting. Because if you're ambitious, that takes a lot of work. If you're passionate, that takes a lot of work. To meet those milestones, if you are ambitious, takes a tremendous amount of energy. Being passionate about a business, like I am about the play, takes a tremendous amount. So there's a lot of areas that are very hand in glove with passion and ambition. And I want us to address a bit the distinctions between ambition and passion. Like what do you think fuels passion?

Dan Sullivan: My sense is each person who's born is on their own and making sense of the world that they're in. And I don't think that we see the world similarly at all. I mean, there's a conventional part of life where you agree to talk about things in certain ways so you don't get into too much trouble. And I'm just going to relate it to what I've noticed about entrepreneurs, because I've got a big enough sample. And what I notice about them at whatever age they're at, we're getting younger ones because of technology, that people are becoming successful in their twenties in a way that wasn't true in the 1970s. You know, that people are making a lot of money much earlier than I remembered life being in the 1970s, 1980s.

But the thing that I find about it is that one of the fundamental attributes that's always there with passion is freedom. You get to do what you want to do, when you want to do it, with whom you want to do it, how you want to do it, and being free of other people's control, free of other people's commands, free of other people's supervision. And I always wanted that. I wanted time for myself, you know. And I remember Morita, the man who Sony, the great Sony pioneer, he was asked at Harvard Business School whether the Japanese would be as innovative as the Americans, now that they were into technology. And he said, no, there's no possibility of the Japanese being as innovative.

And it was kind of a scandalous statement, you know, it was almost racist, you know. But he being one of the other race, he says, no, they're not allowed to be on their own. He says, Japanese children are not allowed to be on their own. And he said, as far as I can tell, all the inventors and innovators spend a great deal of time on their own. They have control over their time. And they can do different things that seem odd, and Japanese don't like odd in their children. But I think they are different, and you can have the one without the others. So I've met people who are very, very passionate, but haven't translated it into a practical ambition.

Jeffrey Madoff: And what is that difference though? I mean, so you touched on it a little earlier today. Ambition's a drive to achieve something.

Dan Sullivan: And it's outside of you.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. And that's the key. That's the key. Because I think that passion, and I can certainly say this for myself, is a love of the process. And, you know, the whole way that you have created your career is because you love that process. You love the discovery of the other's thinking and providing them with the tools to reach their own conclusions, which is also significant as opposed to, as far as I know, you don't give anybody any answers. You just ask them the right questions. So that process, it's like a musician who can jam all night. That process is really important. So to me, ambition's the drive to achieve something. Passion, there's an enjoyment to the process. And I think ambition is more strategic and focused in hitting those milestones or goals where I think passion may be driven more by a sense of personal fulfillment. What do you think?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, I think it's an entirely internal game. You know, we were talking before the podcast started about a really frustrating and failure-filled part of my life. I don't think that failure, you know, one of them was marriage and the other one was bankruptcy. I can't remember them having any impact on my passion at all. It threw me off whether it was going to actually work as something practical in the world. I remember I had a conversation with a bank manager and he says, you have good writing skills. I know that you have good artistic skills. Why don't you just get a really good job and give up with this foolishness? I said, well, there's no possibility of that. And I said, I'm just not smart enough at translating what I'm seeing in my brain so that it shows up in the world in terms of dollars. It shows up in terms of developing a reputation for doing something that other people find useful. And the other thing is, throughout my life, my passion is constant, but my ambition has increased.

Jeffrey Madoff: And when you say ambition has increased, what does that mean?

Dan Sullivan: Well, it's successful, translating what goes on in my brain into diagrams and worksheets and concepts that other people get. They say, I really, really understand what you're talking about here, and that I have a way of presenting a way forward for them in terms of what their passion is and how they're trying to be successful, that I'm creating very, very useful supports and very, very useful structures for them to be successful. And so my ability to do that at age 80 is incomparably greater than it was when I was 50, 30 years ago. I was successful then, but not nearly as successful as I am today. But I would say the underlying passion that keeps me going, there's no change in that. It was 100% back then, it's 100% now.

Jeffrey Madoff: So I think it's safe to say and accurate to say that both ambition and passion are characterized by intense feelings and motivations towards these specific goals or activities. And I think both can propel individuals forward, you know, because it takes dedication and persistence in both cases in order to do that.

Dan Sullivan: But the other thing is that without the passion, the driving passion, the ambition can come to an end.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. Right. That's just what I was going to go into. I think that that's correct, because ambition is so often focused on achieving external success, you know, recognition or income or whatever. Fame. I mean, all of that, which none of that has anything truly to do with happiness. But these are milestones, I think, oftentimes misconstrued because a lot of people, as you know, and I know, hit into their prime in their forties and fifties, where they're maybe making the most money, but they feel hollow, because nowhere in the equation was there room for fulfillment, you know, or acknowledgement. And I think we've seen what that does to people.

Dan Sullivan: Well, yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: The other thing is that for the sake of the outside recognition and payment, people can betray their passion.

Dan Sullivan: Yes. When you say betray, I guess it's the same thing I'm thinking, compromise. It's almost like there are two of you now. There's the ambitious you and there's the passionate you. And the ambitious you said, in order for me to be recognized and rewarded, I can't be paying attention to that. That's what got me to the point where I can be really successful now. And that's not going anywhere. But it's still there. It's still there. But enough scotch will make you forget that. Or the fifth house or, you know, whatever it is. And I can tell when I'm in some place.

I mean, we live well, Babs and I live well, but it's very, very interesting. Our lifestyle was never an ambition. It was a reward and it's neat that you can do this, you know, and, you know, the money's available and you can do that. But it's never been, I can't remember any part of our lifestyle that was ever an ambition. But the freedom at the center of our lives has always been a passion for both of us, you know, and everything like that. And the other thing is that the people who retain their passion go a lot longer in life than the people who are merely ambitious.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think what you said before, which bears repeating, because I completely agree with it, is that ambition may propel you towards a certain goal, but when it gets really difficult, if you don't have the passion, passion fuels long-term commitment. I think that that is the case because the rewards become too far away if you are ambitious, but it's taken a lot longer than you think. And I think we're both wise enough to know at this stage in life that most things take longer than you anticipate.

Dan Sullivan: Well, the other thing is that there's, and I see it in you from one standpoint, is that it's the number of friends that you have from early childhood that have been lifelong friends. They're constant today. The conversation is constantly updated as you get back with them. But there seems to be an absolute consistency about you at six years old and you at 75. It's absolute consistency. And it's very principle-based. It's very principle. I don't think ambition is principle-based. It's strategy-based.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's a great distinction and absolutely right. I think that's right. Yeah, that goes back to passion being internal. Yeah, because I think that ambition focuses on achieving that goal or milestone. And then what? And as you said, if you're not, you know, passion, centers on the process and enjoying that process. I don't like the downtime between when we have finished performances and then at this stage, then getting it back up for another performance. But when we're on auditions and we're in rehearsals and we're in previews and we're in performances, I love it. And it is fulfilling. And I think that's a key difference is that ambition often emphasizes the result or the goal and passion centers on the process and the enjoyment of the activity itself.

I mean, why do you and I do this? You know, I think because there is, at least from my end, an enjoyment about the exploration that we go on each week and it's not like I never had an ambition, and this is gonna be the top podcast in the United States. It should be, of course, the value we put out there. People should realize that and catapult us to fame and riches. But, you know, this is an endeavor that two busy people engage in because we have a passion for that kind of curiosity and discovery. Would you say that's accurate?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and what else are you gonna do on Sunday anyway? It's probably one of the more interesting activities going on at Sunday afternoon anywhere, you know. I'd just like to go back and touch on the principle versus strategy, you know. And the one thing I can't comprehend, and I see it more and more simply because of the years that I've put in, is I openly discuss this in the workshops. And I said, there's one thing that you cannot talk about here in the workshop and it's retirement. I said, one is I have no aspiration to ever retire and I'm not interested in anybody else's thinking about it. I said, if you bring up that topic, I'm just not interested in having the topic. I can't comprehend why you would ever think about not doing what you're doing, but better. I said, I'm sorry, I mean, it's like dying, you know, people talk about dying, you know, and you know, well, I got another 15 years. And I said, you know, your body's listening, your body's listening, you know, and saying, you know, to put that out, I see, I've seen no benefits to death. And I think retirement is a stage of dying.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, certainly for me, because it's a practical decision not doing it, because I don't golf, I don't play cards, and there's something else that I don't do. I forget what it is now. But, you know, those activities, for me, the upside is I am perfectly capable of being alone and going into whatever I want in terms of writing or reading or studying or whatever. I enjoy that time. And a friend of mine said, you know, you're a running joke in terms of vacations that, you know, I said, but I get why you aren't big on vacations in a traditional sense of the word, because you're enjoying what you're doing all the time. So why stop doing that?

And I can make the argument that, well, the fortunate thing with my work is it took me all over the world doing things. And now with the play, I'm going to London, you know, and it's that sort of thing. And I think there is a big plus in experiencing other places and meeting new people, which I do constantly and really, really enjoy. But I think we did a good program on retiring. We did a good podcast on that. And it just happens to be something that's not, for either one of us, anything that's desirable.

Dan Sullivan: You know, I just couldn't comprehend why somebody would want that. You know, I just, they're bringing an end to something, you know. And the other thing is that I think I look at entrepreneurism differently. I don't look at entrepreneurism as a step to getting to where you're not doing anything. I see entrepreneurism as a process of always getting to something more interesting.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think in our culture, you know, it's kind of work harder than your reward at the end of that is that you don't have to go to work anymore. And again, when you're determining what it is you work on, and you're doing things that you have a passion for, why wouldn't you want to continue doing it? That's the point. Yeah, but for those that retirement is the reward for having, in many cases, having to labor at a crappy job for 40 years, you know, that's just, I understand. I also understand if somebody says, you know something, I want to spend the next 20 years traveling the world. And retirement is the only way I can do that. You know, I mean, I can understand it. It's just never, by the way, by the same token, I never, ever thought about getting a good job somewhere. Getting a job was just not, that wasn't part of the script.

Dan Sullivan: There is no such thing as a good job.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes. That was a contradiction in terms.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Yeah. And, you know, this is really, it's sort of a, it's a way of being. When do you want to give up your way of being? And I said, well, you know, because my way of being is that what lies ahead is always more interesting than what lies behind as long as I'm in motion. So, you know, I know I'm 80, but I said being 80 isn't really that much different than being 70, 60, or 50 before that. I mean, there's certainly my understanding of what has led to where I am right now has gotten more interesting to me, you know, how I stuck with it.

And I'm at the point, I mean, this is just in relationship to what I'm doing for a living, which is coaching entrepreneurs. I started doing it before there were any of me. And most of the ones who also did this at the same time aren't around anymore. And the others are not doing it in any of the way that looks like the way I've done it. And I've done it all through questions. I haven't done it through the answer. The business world is filled up with people who have the latest answer, which lasts for about 90 days, and then there's the need for another next answer. But the questions are pretty permanent.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, and what's interesting now is, I remember for my parents' generation, and he wouldn't have called himself a coach, but so many people had Dale Carnegie's book, How to Win Friends and Influence People, which is basically about …

Dan Sullivan: Well, and I tell you, there hasn't been a book written that's better than the one that he wrote.

Jeffrey Madoff: And, you know, I mean, it's interesting, but I also think that it's also very effective ways of masking behavior, you know. That's why I liked Lenny Bruce's book, which is How to Talk Dirty and Influence People. You know, Dale Carnegie, and I'm trying to think of the other, there was another guy, who was power positive thinking?

Dan Sullivan: The big ones back there, Earl Nightingale was a big one. I think positive thinking, he was quartered right in New York City. I think he was a minister, actually. The person who the positive thinking.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. I'm blanking on the name, but I think that's in a sense what passed for coaching, because I also think that at that time and we're going back, I think I'm sure Dale Carnegie's book was written in the late forties or something like that. People weren't self-reflexive. So it became more of, you know, a behavior modification of what you can do to win friends. And I think it was that, but it's none of these questions have gone away. You know, they're still around.

And I think that, you know, I've said this to you before, you're involved in a never-ending detective story. And you help these people gain solutions by giving them clues to questions they can ask themselves without ever giving them the answer. Because I don't think answers come without discovery. Opinions do, but answers are something else. So it's interesting because you talked about that with ambition, if there's not passion, the time can run out. You can just be discouraged by how hard it is, how long it takes, and your ambition doesn't take you far enough to deal with that kind of thing, where I think passion, it's not about a specific job or career or anything, it's an emotion that is expressed through the various activities you're involved with and what you're doing.

And as you said, you know, it's really interesting. The question became for you, you know what you love doing, talking to people, you know, getting that feedback, eventually getting that reward, then you wanted to make it into a business. Because you knew doing that made you happy. So how do you make a business out of what makes you happy? And I think that's a challenge for a lot of people. And I think that that's the part that requires the passion because passion helps you endure the disappointing times.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. I think that you and I right now, the two have fused, the passion and the ambition. And the reason I'm saying it is our age. I would say you don't get much past your sixties if both the passion and the ambition aren't fused together. And what I notice is that when people don't have the ambition anymore, they take the passion and they put it into other activities. So for example, I'm not involved in any philanthropic work or anything like, I don't sit on board, I've never sat on a board. I've never gotten involved in other people's businesses. I'm not on the speaking circuit. You know, if we put out the word that Dan is available for keynote speakers and that my schedule would fill up. Okay. I'm not the least bit interested because it's basically talking about the past and I'm not interested in the past.

It's like athletes and there's no more sorry people in the world than professional athletes beyond retirement. I grew up in the Cleveland area, you know, I met one of the players who had been during the golden years when the Browns, you know, were almost in the championship game or would, were of that quality that they could have been in the championship game. And he's an insurance agent. And, you know, not at his playing weight, you know, anymore. And there was just a sadness about him. You know, and professional athletes, you know, they're old at 35.

And they've lived in a structure, you know, they're spotted early. Usually they get really good coaching from an early age. They're, you know, they're bigger, they're meaner, they're faster, they're stronger. They're more competitive at 10 years old than all the other kids who go home crying for something that they love doing, inflicting pain on others, you know, and they make it, but they have a very short window in which to make money and secondly to get it. And I met them and I said, geez, you know, but they have no future beyond the game that they're playing. And the game came to an end.

I was just reading. They still don't know what happened, but the reports of Gene Hackman and his wife being found dead. And I said, yeah, I said, how did all three of them do it at the same time? You know, and the other thing is they must have not had any friends because they think it may have been weeks ago that they found them. And I said, you know, Gene, boy, you were you were so great, you know. And his wasn't an occupation on the male side that you really have to retire from. I mean, Clint Eastwood is still doing great work in his nineties.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, in ‘94 he just had his film, Journal Number Two, came out recently. Yeah, got good reviews and everything. He has a great phrase, which is, every morning he gets up and his goal is to keep the old man out.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. So anyway, I mean, everybody's about this, but people question, they say, well, do you think you're going to die? I said, yes, I will. And I'll be on stage, but not today.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I mean, my thing is, I still consider myself middle aged, you know, but I'd have to live to be at least 150. That's the case. What do you think? Because I think that in certain levels, as you said, ambition and passion are fused. What do you think that ambition is primarily fueled by?

Dan Sullivan: I think recognition. It's the Laurence Olivier story that you tell. Why do we do this? Why do we do this? It's the recognition. Look at me, look at me. Yeah, I think it's recognition. And I think that's prior to money. I think that's prior to anything else. I think the recognition, you know, and I think it's probably recognition of something great.

Jeffrey Madoff: So this is a, I know will be a rough estimate, but I'm going to ask the question in over the years in the large number of entrepreneurs you've worked with, how many hit a point where the disappointment with how long it took, how hard the journey is or whatever, because personal fulfillment was never a part of their equation, how many of them became disillusioned or depressed or whatever in spite of having made a lot of money?

Dan Sullivan: I think a lot. And not to be claiming too much by doing this, when they stop coming to the workshops, I know that they're coming close to the end. Because the workshops are about planning the next quarter. That means they didn't have another quarter to plan. And I kind of know, yeah. I mean, the oldest continuous I have is 70, and I've seen him every quarter for 38 years, and I just saw him about six weeks ago, and as excited about the next quarter as he was the first quarter in 1987. Just totally excited about the next quarter.

Jeffrey Madoff: Do you feel that your work has had, not just feel, do you get feedback also, that your work has had a positive impact?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: And how does that make you feel?

Dan Sullivan: Once I passed 70, they started using a word. And the word was the legend. And I said, I said, I like the sound of that. The living legend. But more and more, you know, and it's just unusual, because if you think you've had enough contact through Joe, Joe Polish, and doing this, that most of the, you know, the go-getters and everything in this world are in their forties. I'm twice that, you know. I was coaching before they were born, you know. But if I look at what lies ahead, like our book project, What Lies Ahead, this is a big book, you know, that we're working on right now. We're hitting some very, very fundamental issues that are facing employment throughout the 21st century, the casting not hiring. I mean, and I think that's the instant response that we've gotten to the cover title of the book. It said, people are looking for this. And I've never had any idea that has gotten the response that this one has over the last year.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I was, you know, it's my ambition to light you up so it lights us up. We're doing something that we are both passionate about.

Dan Sullivan: No, no, this is very, I mean, college professors think this is an amazing idea. Surgeons very high up in the medical world think this is a big deal.

Jeffrey Madoff: On Friday, I interviewed one of the people, the senior vice president in charge of HR globally for Sachs. And he was with, prior to that, he was with Michael Kors, Victoria's Secret, Ralph Lauren, major, major global brands. In his office, he said, I had the book on my desk. And people were coming by and they'd say, oh, that is cool. Wow, that's neat. Oh, Casting Not Hiring, oh, that's really cool. Again, knowing nothing about what was between the covers.

Dan Sullivan: I've never had a response to any, you know, three words. It's three words.

Jeffrey Madoff: So I think that that's, again, there's an example of passion being ignited, ambition being a partner in that, and the fulfillment that one gets, in this case, to get, from pursuing a mutually exciting idea. Yeah, which is very cool.

Dan Sullivan: No, no, I mean, this is worth the 50 years that it took to get here. No, no, no. I mean, it really is. And I've had full confidence that that idea is out there. I mean, you have to test and test this idea, that idea, this idea, but there's an idea that you're going to come up with. It's really interesting that everything that Einstein is famous for today was written in a three-month period when he was 26 years old.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, that kind of thing is always interesting, and that he failed math and, you know, all that kind of stuff.

Dan Sullivan: He didn't, by the way.

Jeffrey Madoff: Pardon?

Dan Sullivan: He didn't. No, I mean, there's a lot of legends. I mean, it makes us sound good and everything. He knew his math. He might not have been interested that day in the test or the program, but he didn't.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, clearly he knew it.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, but I think his great stroke of luck he had is that he didn't have a lot of money and he had to pay his way through college in Germany by being a patent clerk. And he was famous for taking ideas not very understandable and making them into a very simple explanation for the Patent Bureau in Germany, that this is what this does, and all his patents went through. He was a phenomenally good communicator of abstract ideas and practical examples. That's why I like reading Michael Lewis.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, yeah. You know, I think that that's a certain gift, you know, to have that. So where do you think we came out today in this topic?

Dan Sullivan: Well, the one question we haven't asked is, does everybody have passion and ambition? And not in my experience.

Jeffrey Madoff: Same here. Same here.

Dan Sullivan: And the ones who fuse them together, ambition and passion, even fewer.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. And, you know, it's interesting. People will say to me and people I don't know well, or people that I just meet after one of the performances of Personality. I've been asked this probably, oh, God, I don't know how often. I was really difficult dealing with those actors. And I'm thinking, you know, I still have some filter left, not much. I never had a very good start. You know, dealing with you is the pain in the ass. I love people who are passionate about what they do, who are excited about what they do, who want to share what it is.

Dan Sullivan: Well, not only that, they're putting their life on the line.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right. How can you hate people that they're putting their life on the line? I mean, yeah, well, and that's, you know, whether you're acting a part, even shitty actors are putting their life.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. Even more so. Yeah. But that you know, I think that that’s really true. But I think that people—and I think this is cultural, just like, you know, I think that older people are not valued in this country for the wisdom they've accumulated and all of that. There are, of course, some that are, but, you know, culturally and then culturally our feeling about people in the arts, you know, are they a diva? Is this temperamental? And I said, you know, go to your local UPS facility and you're gonna find somebody on the staff there that's temperamental and a pain in the ass. It's just that you don't happen to know who they are, but you may have heard of an actor who supposedly do that. And I don't think that people realize also when you put your passion out there and you bet on yourself, that can be very seductive and that's how you get investors and that can be very seductive to some. But I think to a large part of the population, they are afraid.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And I can understand too, because they don't have the equipment. You know, I mean, first of all, I think that most people's capability requires them to be hired. You know, they don't have the ability to hire themselves.

Jeffrey Madoff: And when you say they have to be hired, tell me what you mean.

Dan Sullivan: You know what I'm saying? They need an employer.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right.

Dan Sullivan: In order to give them a structure to function in.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. You know, and, you know, it's a roll of the dice. I don't know how I have the foggiest idea. I know that none of my siblings have it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think that, look, thank goodness for all the people that are doing all the things that we don't want to do. And it's a big world. And there's a whole lot of things. And I think about, you know, fairly self-reflective. And I think about the things that I have done. And, you know, I've been asked the question, you know, many times when I've been interviewed is, if you had it to do all over again, what would you do? And my answer is, you know, buy Apple and Amazon in the eighties. That's what I would have done. Although I do like Groucho Marx's answer even better when asked when he turned 80 and he said, try more positions.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. I think the one thing that's notable to me, if they're doing it in their seventies, the passion and ambition got fused. I just don't think you make it past, with all the social pressure to pack it in at 60, you know, that there is. And it's there today. Well, this has been … this is a great subject.

Jeffrey Madoff: You want to wrap us up?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, I'm excited about this. And just to relate it to our book that's coming out in November, Casting Not Hiring, I think the entrepreneurs who take the idea of having your entrepreneurial business structured on the lines of a theater enterprise will be the ones who have both passion and ambition.

Jeffrey Madoff: I agree. Thanks for joining us today on our show, Anything and Everything. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend. For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

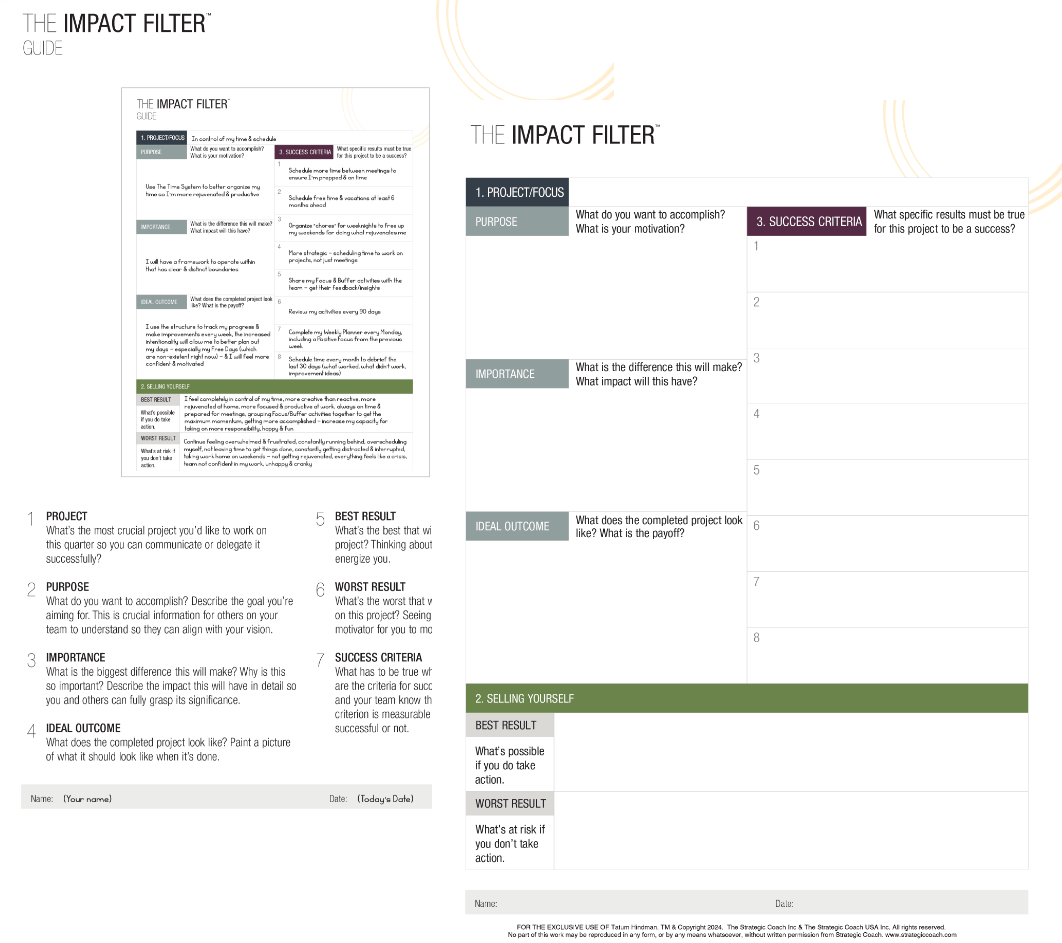

The Impact Filter

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter™ is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.