What Young Entrepreneurs Miss About Timing

January 06, 2026

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

Are successful entrepreneurs always young prodigies? Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff dismantle the myth by showing why most real breakthroughs happen in midlife, after years of sorting out direction, taking financial responsibility, and learning directly from the marketplace—especially from rejection, rough patches, and so-called late starts.

Show Notes:

Despite the hype about young founders, the average age of successful entrepreneurs is somewhere between 40 and 45.

More young people are trying entrepreneurship than ever, but many are still using their twenties and thirties to sort out who they are and what game they want to play.

The moment that you first have to create the money to pay for yourself is the true starting line of your entrepreneurial life.

Entrepreneurs don’t hunt for “good jobs”; they look for a compelling opportunity, create value, and build jobs around that opportunity.

Many entrepreneurs initially measure success by reaching a specific financial benchmark, only to discover that progress and impact matter even more.

Younger entrepreneurs often hesitate to take on overhead because they don’t yet feel financially safe enough to make bigger commitments.

The pandemic pushed many people to experiment with entrepreneurship, but that surge in attempts didn’t change the typical age at which real success shows up.

Every successful entrepreneur has weathered rough periods where cash was tight, models weren’t working, or personal setbacks tested their confidence.

Most people avoid a direct relationship with the marketplace because it involves uncertainty, visible performance, and constant feedback.

For entrepreneurs, rejection is essential market data; if you treat it as failure instead of learning, you’ll do everything you can to avoid it.

Resources:

Casting Not Hiring by Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff

Your Life As A Strategy Circle by Dan Sullivan

Episode Transcript

Jeffrey Madoff: This is Jeffrey Madoff, and welcome to our podcast called Anything and Everything with my partner, Dan Sullivan. How are you doing, Dan?

Dan Sullivan: I'm very, very eager because we're going to undermine a myth today.

Jeffrey Madoff: I love undermining myths. Yeah, you know, despite some very highly publicized examples of young entrepreneurs, the research indicates that the average age of successful entrepreneurs is closer to middle age, somewhere between 40 to 45 years old. And there are more young entrepreneurs, young people attempting entrepreneurship than ever before, but there's also mitigating circumstances for that too that I think are quite interesting. So I'd like to start with just, I can't think of anybody better than you who is often in front of an audience of all entrepreneurs and that's who you work with and wondering what your take is on that.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, you know, if I look at the record of entrepreneurs that we've had since, mine goes back to 1974, so it's 51 years. You know, if I just take everybody that I've personally dealt with in our program, you know, we're about 25,000 that have been in Strategic Coach so far. I wouldn't be surprised if we averaged it out that the sweet spot for them is certainly in their early forties. And one of the reasons for that is that I think that—most of my experiences with males rather than females, so the vast majority of the entrepreneurs that I've personally coached and those who have been coached by other coaches in our program. There's a sorting out that I think individuals do, just quite frankly, in life. They sort themselves out between 30 and 40. And the real results of those who have had sort of a successful approach, a successful organizational structure, usually happens in their early forties, and that's different when they actually start, you know? When's the first time that you were in a situation where you're the one who had to create the money to pay for yourself, you know? So that's really the point at which you become an entrepreneur. So I think it differs. I started at 30. You were younger, if I remember. You were, what, 25?

Jeffrey Madoff: No, I was 21.

Dan Sullivan: This would have been after university or during university?

Jeffrey Madoff: The real entrepreneurial aspect was I had graduated.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, okay.

Jeffrey Madoff: And, you know, I was working in that store that one thing led to another, you know, started a company.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: But I was 21 there. I graduated early. Just as a sidebar, it was kind of funny because …

Dan Sullivan: Was that because they wanted to get you through?

Jeffrey Madoff: Get me out of there. Get him out.

Dan Sullivan: I was trying to get who was most eager that you should leave university.

Jeffrey Madoff: Me. Which I, for the most part, really liked. The University of Wisconsin in Madison. I had no idea what I was going to do, you know, no concept of what I was going to do. But, you know, the entrepreneurial background of my parents and the behavior that that modeled for me is, I think, sort of set my destiny in motion that I wasn't going to be looking for a good job. I was going to be looking for a good opportunity to create jobs and create a business as a result. I always took the maximum number and actually got permission to take additional courses so I could finish. When I realized my junior year that I was really a semester away from graduating and I could graduate early, I, you know, did that. So it was just because I took the courses I liked. I didn't care what the load was because I could always handle it. And then I ended up that I had accrued enough credits that I could graduate a semester early. So I did that. But I had the job of working in this store that started the whole thing while I was in college. But that was kind of the platform.

Dan Sullivan: So in relationship to the opening context here that usually entrepreneurs are successful in their early forties, how did that line up for you? Were you earlier there?

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, that leads to another really interesting question, which is, what is success, you know, and how do you do it? Are you, you know, many entrepreneurs quantify success as getting to a certain financial point, you know, a certain level of business that can be quantified and all of that. And it's funny, you know, our book, Casting Not Hiring, you know, in a way, when I've been talking to people about that and they've asked me about my career, I've said, you know, I've actually been doing improv since I left college. You know, I didn't know I was going to be a designer. I didn't know that I was going to get into the film business. I didn't know that I was going to be teaching on a college level. I didn't know I was going to be a playwright. So it's been improv based on truly what lights me up and the confidence that whether ill-founded or not, the confidence that if I really wanted to do it and it was something that really engaged me. I've never been able to get engaged by a deal. I'm engaged by the topic and how I have to spend my time. And what about you on that? I mean, when you were starting out, because for me it was always, oh, this really seems interesting. And I tried to figure out a way and was fortunately successful at how to make enough money to live to do that.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, mine was mainly driven by a particular type of activity that I really loved doing. One is that it was conversational activity. And if I go right back to the beginning, which was ‘74, the activity itself actually started before I left the ad agency where I was working. And it was a set of circumstances that I was a new writer. And agencies are merger and acquisition creatures. You have an agency that before I joined them in 1971, they had probably gone through five or six mergers and acquisitions over a 15-year period. Okay. And what they're looking for are the big media buy clients. You know, you grow your agency so that you have credibility that you can handle really big. We had Kraft. Kraft is a huge corporation. We had Chrysler. That's a huge corporation. And then we had one of the big Canadian banks, which are monstrous, like TD Bank. I mean, the smallest of the Canadian banks has 800 branches. So these are really, really big outfits. And of course, they're doing TV, they're doing, if there's a way of promoting yourself, they're doing it. And there's a, you know, a 17%, 17.5% take for all the media that you place. So they make their money on the big accounts.

But along the way, they've accumulated a lot of little ragtag companies, which are personal relationship sort of clients. Somebody who's important in the agency has people that they're doing fee-for-service. And I was the fee-for-service writer because they weren't paying me anything, so they might as well put me on the accounts where they're not making any money. These are family businesses and would have been like your parents, you know, would have been like your parents. They're doing advertising, but it's not media placement. It's just wherever they're doing their placement and whatever involves advertising for them, well, then that's taken care of by a writer. So I was the main writer for probably 10 companies, little companies.

And it occurred to me that their problem wasn't advertising. Their problem was they didn't have any future. They didn't have a goal ahead of them that represented too much more than what they've already been doing. And a lot of them were getting to the point where there was gonna be a generational change in the company. So they had never really given any thought that they would have a strategic plan for growing the business. And I was, you know, I was very interested to say, you know, three years from now, where do you see yourself? And have a conversation around that. And then we would have, if you think about it, a flip chart size sheet of paper. I would do boxes and arrows and stars and everything else.

Jeffrey Madoff: The early Dan Sullivan tools.

Dan Sullivan: I was doing the Dan Sullivan routine. And, you know, you tape them to a wall and you make sure that the magic marker didn't go through and mark up the wall. And I would just get them involved in a conversation. And that was my joy because that's what I'm doing today, 51 years later.

Jeffrey Madoff: So unlike me, I mean, your parents had a farm. Then a landscaping business. So they were entrepreneurial also.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: In a very different world.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: What was it with you that made you think, well, this could be my business? Why didn't you continue to do advertising, ascend through the corporate levels? What turned the corner for you and how old were you when you wanted to enter the world of entrepreneurship and why?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I would say 30. I would say 30 was, I liked advertising. I mean, I liked it, but first of all, you could tell that most of the hotshots in the advertising world, the people who were really doing well and knew they were doing new things, weren't very old. A lot of them were in their twenties and thirties. And I looked at the people who were in their forties and fifties. And they weren't excited about what they were doing. I mean, they were making good money, but it wasn't exciting. The other thing, this was in Canada. And if you took a company like Kraft or you took a company like Chrysler, the two big U.S. accounts, all the creative was being done in New York. And you were modifying it and adjusting it for Canadian use, but it wasn't real creative. They had some Canadian clients where they were doing really interesting things. And then, you know, I began talking to people, and it was a lousy lifestyle for one thing, advertising. It was feast and famine in terms of the work. You'd go for a week, and you were just tidying up, and then you'd have a massive deadline. You were getting two or three hours of sleep per night, and kind of exciting. It was kind of exciting and everything else. But you could see doing that for decades of your life, you probably wouldn't end up very well. They were heavy smokers. They were heavy drinkers. I wasn't tending in that direction, but you could see why they did it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, but what made you think, you know, I could start my own business talking to business owners? You know, how'd that come about?

Dan Sullivan: Well, it was actually the little companies that I was working with in the agency. They really liked the conversations. You know, they had never had consultants working for them. They had never had anybody. And here the advertising guy, the guy who was supposed to be writing the ads, and I did write the ads, was the person who was asking them the questions, not related to advertising, but, you know, just why are you doing this anyway? You know, would you like the company to be better? Would you like the company to be more successful? Would you like to get into different markets? And I'd been in enough big meetings with the big accounts that I knew the type of questions. But the copywriters and the advertising people are only looking for the thing that was solving the advertising issue. But it seemed to me it wasn't an advertising issue. It was a company issue. And it was an ownership issue, you know, what they were trying to do. And I really liked that conversation. And then nobody, their accountant didn't ask them these questions. You know, their lawyer didn't ask them the questions. Yeah, so I just created this activity of asking questions and them being excited about the answers. So I had five or six of them. And it occurred to me, I wasn't making much money in the agency, it occurred to me that if I wasn't in the agency and I was doing this, first of all, would it be possible? And then secondly, would these particular individuals be the first clients?

Jeffrey Madoff: Did you immediately open an office and assume certain overhead? In the video company, my first client was Halston, the designer. And I would go to his incredibly luxe showroom, which was across the street from Saks Fifth Avenue, at the Olympic Towers. They had 18-foot windows all around, looking out over the cityscape, and it was amazing. I'd be sitting there with Halston, and I'd say, I'm sorry, I've got to get to another appointment. You know, I didn't have an office either. And so when I started out, I would always say, you know, I happen to be in your neighborhood at that time. Why don't I just stop by your place? And I'd be meeting with Halston. This happened more than once. And, oh, you know, I've got to go. I've got another appointment I've got to get to. And, you know, can we continue this later? What he didn't know was that that other meeting I had to get to was at the unemployment office, so I could collect my benefits. And that's what I did initially, until I finally took some office space. But it was funny, some of the illusions we try to create in terms of our business and you know, as you were saying, some of these companies in advertising you had to prove that you were large enough to handle their business.

Sears wanted me to become part of their contemporary line of clothing for young men and women and was at a meeting at the then rather new tallest building in the United States Sears Tower in Chicago and I needed, literally, I would have had to have hired a few people just to manage their account. And I said to them, you know, I can't afford to do business with you. You know, the cost of doing business is just too high. You know, because they want you to warehouse it, pick it, and ship it when they want it, take all these returns. I mean, it's a whole business within a business just to support what was then kind of the Amazon of its time. You know, Sears has everything. So yeah, it's funny starting out. When did you feel financially safe enough to take on some overhead so you didn't have to do everything. Because that's a big problem that I think young entrepreneurs have.

Dan Sullivan: It's just … the one thing, if I go back then, you know, this is 1974. I've never accumulated too much overhead. And it wasn't until we were successful that I actually ever had an office. The other thing that I think was interesting about it is that I made the break with the agency and it wasn't acrimonious or not because my boss, he was the creative director and he was the half owner of the agency. And he was a street kid from Detroit who, you know, didn't go to college or anything. So he was out hustling on the street from his maybe mid-teenage years. And I think he totally got what was happening to me because it had happened to him. Except I think he was an entrepreneur, I mean, in the sense that he wasn't making any money unless he was selling something when he was in his late teenage years. So I think he had a real feel for someone who would be an entrepreneur.

And the other thing is that I was lucky that I had developed kind of a methodology. It was sort of a way of going about asking people questions. And the people who really appreciated it weren't just so much the people who had products to sell, they were people who had services to sell. Because services don't need warehouse space. And the other thing was that there was something happening in the economy, something that's happening in the marketplace that gave me a sense of what the future was going to be like. It was a series of articles in The New York Times, 1973. So I set out a year later, and he was talking about this new invention, which was called a microchip. And he was talking about, there was about five or six articles, technology writer for the Times. And what were microchips had been around for about 15 years, but they didn't have a name. And the name microchips started coming in in the early 1970s. And he said, this is going to be the greatest invention so far. And the reason is because it can be applied to all the other inventions that already exist.

Not only that, but as these microchips, and they had the progression, you know, there was a history to these microchips as they got more powerful every two years. It's called Moore's Law, and you know, it still is a topic of discussion. And it's processing information. So right off the bat, there was a big picture that was emerging for me, that this invention called the microchip was going to have a profound impact on the marketplace. And the predictions of the writer were that big companies were going to have a hard time with this invention because it was going to speed up information, it was going to speed up change, it was going to speed up new challenges in the marketplace. And he said, you know, I think what we're going to see is an explosion of entrepreneurism. But that never happened. This was 1974. That didn't really happen until 10 years later. That's when the personal computers came in. I think IBM was the first. I think it was 1979 when you had legitimately what a personal computer could be. It was a tough decade for me. I really earned my confidence by going through a very tough decade. ‘74 to ‘84 was really tough.

Jeffrey Madoff: Because?

Dan Sullivan: Divorce, a couple bankruptcies. So I was married. I'd just been married in 1973. And if you could think of five characteristics of someone who would probably end up hating entrepreneurism, it was my wife. And then she personalized her hatred of entrepreneurism and focused it on me. And what's called woke today, the whole concept of woke, she had that in 1975. It was business and it was capitalism and everything that was causing all the problems in the world. So the easiest part of my life for about five years was going out and getting rejected in the marketplace. The real trouble started when I went home at night.

Jeffrey Madoff: The rejection continued.

Dan Sullivan: The rejection, yeah. Anyway, so I had to go through that. And then I didn't really have a sense of the business model. You know, and the big problem is while you're delivering the service that you get paid for, that's using up time that you needed to be out marketing. So, you know, it took me 10 years to get the model, but then I came up with what today is called a thinking tool. It was called a Strategy Circle. And first of all, I had it sort of conceptually. I could draw it on a sheet of paper, and then I got to the point where I could go to a printer and have the sheets printed out, and everybody went through the same. And interestingly enough, I was 42 when I had that breakthrough. And it was a sheet, and it was called a Strategy Circle. And first of all, you'd get people to establish a vision. I'd say, okay, we're gonna go into the future, your choice of when the future is. And they would, I'd say, is it a year out? And I found that you never wanted to go more than three years out. You would say, so on a day this day, three years from now, what would be five bigger, better results for you than you have right now? And you'd write them down, you'd put numbers to them and everything, okay?

And then I'd say, okay, now tell me 10 reasons why that can't happen, and they would fill in little boxes, you know, 10 reasons why that couldn't happen. And I says, no, we're gonna take each of the reasons why this can't happen, and we're gonna create a strategy of overcoming the obstacle so that the breakthrough from the obstacle actually creates the result you want three years from now. And that was gangbusters. So that was ‘82 that I got that. And that was within a month of meeting Babs Smith. And she had a business. She was a top-notch therapeutic massage therapist. And she had a really interesting client base. She had air crews from the airlines. She had stunt people from the movies. I mean, they really beat themselves up. And she had ballet dancers. And heavy stress, psychologically, emotionally heavy stress, airline crews, stuntmen, severe damage to their bodies, and ballet dancers, which is, you know, kind of one of the dumbest things that you can do to your physical frame.

And she got a reputation, but she had been at it for about five, six years, and she was getting tired of it. And I just met her, we were friends, you know, for six months, a year, we were friends. And I had actually used her for massage. And I told her about my Strategy Circle idea. And she said, could you do that with my business? And I said, sure. I said, couple hours. And we did, and we talked it through, and I drew it out for a big sheet of paper. And when she got finished planning session, she said, this is gonna be really big. And I said, your business? She said, no, what you're doing is going to be really big. She said, I got all sorts of friends. I need this, what you're doing. And some of them did, some of them didn't. But I had really, by that point, developed enough of a reputation with the right number of people who were in networks of entrepreneurs that the word went out.

When I formalized it more and more, I said, this is the way it works. I have a method. And this was the right time in the 1980s to have a method. So it was a structure, a thinking structure, and I didn't have to know anything about their business. The only thing I had to know was that this is someone who could visualize the future for themselves and would honestly answer the questions that I would ask. And then I would document it. And then, you know, I had typists and I had, you could take it to a blueprint shop where they do architectural drawings and they could take the drawing and they could formalize it and you could give it back to them. The other thing that was a real breakthrough for me is my two bankruptcies. I had one in ‘78 and I had one around ‘82. They were because of receivables. Receivables. I was supposed to get paid a month after I did the work. It was two months after the work and I was too close to the cliff and I went under. So I made a rule in 1984, everything's up front. All the money's up front or I don't start. And that's been that way for, it's been that way now for 40 years. All the money's up front. You never have a receivable. For an entrepreneur, life gets really simple if you don't have receivables. And you don't have to chase the moment.

Jeffrey Madoff: Were your first clients people that you had met through your previous employment?

Dan Sullivan: No. I mean, my reputation at that point was that I was part of the agency once I wasn't part of the agency. First of all, they weren't being charged for it. The agency just said it's a service that we can provide to them. Then you had to work out pricing. You know, I mean, pricing is a real talent. Knowing how to price is a real talent.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, and the reason I asked that question is that by the time you started, when you were saying you were 42, I started at 30.

Dan Sullivan: Right. You started at 30. I was 42 when I had the breakthrough.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. And, you know, one of the things that, you know, the stories of young entrepreneurs, Bill Gates or Mark Zuckerberg, that sort of thing, you know, that makes great copy and great story and also a lot of mythology and everything else. But in your case, one of the things that happened was that you had gained experience, you had started building a network, you knew how to talk to people, which my guess is none of those skills were that finely honed when you were in your early twenties and working. And so one of the advantages of age is you've got a certain foundation, both in contacts and so on and experience that I think is a huge help. And I think that so much of the mythology of entrepreneurship has to do with focusing on those young success stories, which are by far the exception, not the rule.

Dan Sullivan: Oh yeah. Yeah, I mean, you're talking about the one, you're not talking about the other 9,999 that didn't make it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Exactly, exactly. And I think that one of the reasons that the numbers of people at least trying to be entrepreneurs, I think that COVID was a real turning point for a lot of people because they found themselves at home. Many found themselves out of jobs. And the question was, what can I do? What can I do? And I think that it became almost a necessity to try to do something on your own because there didn't seem to be the same kind of opportunities that there had been. And, you know, most Americans don't have that much money in the bank to withstand, you know, what is the average can't even meet a month's rent or something like that. I mean, it's tough for people. And so I think that there was a whole lot of, I think there were a whole lot of attempts, not necessarily successful, because it didn't change the average age where entrepreneurs become successful. Again, it's very, very, very few that do that when they're in their early twenties. And especially to the level that some of those businesses went. And how much better equipped did you find yourself to be when you started out in your thirties? And by the time you had the breakthrough, what would you say was the, if you can, what was the essence of the breakthrough that shows you there's a real future here? This, this is what I'm going to be doing.

Dan Sullivan: Well, I don't think that there was any alternative. One thing that got me through the tough period is that it was only a question of when, it wasn't a question of if. I have a fair amount of personal confidence that whatever it takes to go through the learning stage to understand what a success model looks like, I'm going to do it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Did that confidence come from, you're coming off a divorce, you're coming off of two bankruptcies, that's usually not the strongest foundation for self-esteem. What was it with you that made you think, but I can do this?

Dan Sullivan: You know, I had a picture in my mind of what it would look like when it was successful. You know, when it was successful, I had a picture. And, you know, one is I think I'm really tough. I'm a really tough character. There's actually quite a bit of forgiveness. And the divorce and the first bankruptcy happened almost simultaneously. So there, I gotta figure out how to say this. And I can remember having hardly any money. I had enough money for rent and everything else. And I said, you know, if I can get through this, this is going to be the toughest part of my life. And it'll be behind me. It'll be behind me. And the other thing is the world was changing, Jeff. I mean, a lot of people don't realize, they're talking about AI today. But things were shifting enormously in the late ‘70s. There was an enormous amount of shift going on. And the excitement about new technologies, especially microchip, the only question is, could you get them into a small enough package that would be inexpensive enough that a large number of people could actually use them? It was a tough period. It was the inflation period, the huge inflation period. Now, I don't remember ever getting to the point where you may just have to have a job for the rest of your life. You know, you may have to just go and do it. It never occurred to me that that would be an alternative. Yeah, and I will say this, because we're talking about the successful entrepreneurs, I haven't found one yet that doesn't have that in their background.

Jeffrey Madoff: That doesn't have what in their background?

Dan Sullivan: The rough periods, rough periods. Yeah. I mean, there's a story of Bill Gates. I think he grew up in Seattle, but I think that when he started creating what became Microsoft, I think he was in Texas. I think he was in a, he had kind of like an industrial building. They were behind in the rent. And his dad's a millionaire, so I'm sure he had money that he needed, a certain amount of it. And he went to the landlord and said, would you take stocks in the company instead of the rent? And the guy said, oh, I know you guys. He said, I can tell. No, no. He says, I want the cash. It would have been better to take stocks. Well, you know, Jeff, it's all guesses and bets.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, true. Yeah. True. You know, those stories, and just like the guy that painted the offices at Facebook and got stock, you know, who knew? It's almost like winning the lottery probably in terms of the odds.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. You know, I'll tell you something on the investment, you talk about the entrepreneurial side, you know, one out of 10,000, it's true on the investor side too. My first IP lawyer, great guy from Silicon Valley, John Farrell, he only dealt with start-ups. His entire business was start-ups. You know, he would do the IP for start-ups. And as part of that, he could get stock as part of the deal. They had to pay money, but he could also get stock. So I asked him one day, I said, right now, how many companies, Startup companies, do you have stock in? He says, about 70. He says, usually around 70. And I said, how many of them have to really make it for it to be worthwhile? And he said, three. He says, that's pretty much the odds of how many of them. And I mean that. Can they pay their bills? Yeah, but that's not the breakthrough they're looking for. They're looking for the big breakthrough. And he said, yeah. And he had Facebook as one of them.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and there have been people that have been good pickers, you know, in terms of that, but I'm sure they get better as you go along. And I'm sure that among those who are in, well, and they also get involved when it's more de-risk too.

Dan Sullivan: Also, they have much more advisory control in the early days too.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and I think that again, all of these things belie the fact that those sort of connections, that kind of experience and knowledge that can help and inform your decision-making, usually comes at a later stage in life, not right out of college. Which I think is interesting.

Dan Sullivan: Can I ask you a question? Because we're talking about my tough period here. And I would say that easily there was a five- or six-year period of my life where my sticking with it defied logic. And what would you say is the makeup of a person who will go through long periods where what they're doing is defying logic?

Jeffrey Madoff: Commitment. Commitment to an idea. and probably obsession with realizing that idea. Because if you don't have that obsession and you don't have that commitment, I think the chances of making it are extremely slim to non-existent. And they have to have some sort of talent, too. Yeah, but sometimes that talent is manifest through the perseverance that they have. I don't know if it's a talent, but the ability to persevere when all is telling you no. And I think that that perseverance is really essential. And I was at this event the other night, on Friday night, and coincidence held at different people's homes. And it's very cool. I met a lot of amazing people. This happened to be held at the home of the woman who was the CEO of Soho Repertory Theater. And so there were a few of the guests that were there that weren't producers.

One of them, the woman Eva Price. She and I met probably in 2017. And she was interested in GMing, you know, being a general manager of Personality. You know, she's very bright. I really liked her. And she was, you know, at that point, not what she is now, which is a multi-Tony Award winning, Grammy Award winning lead producer. And it was funny because I hadn't seen her for a few years, and they look at each other, do a double take, and hug each other, and it was so great to see. She says, I was just talking with someone about you two days ago. I was in London, and I said, who are you? She said, I'm trying to remember who it was. I said, Simon Woolley? Yes, and I said, he's my general manager in London. She says, yeah, and I was so happy to hear that Personality is alive and well and doing, because I think that's so great. And I said, well, you have done such an extraordinary job. I met you pretty early in your career, and now the success that you've achieved is incredible. And she said, well, thank you. And I said, takes some perseverance, doesn't it? And she laughed and said, oh yeah.

That's the main thing. And I think that a lot of people don't realize how hard it is. I think that there's a misconception because so many people bullshit about this stuff, you know? And so anyhow, it was interesting because we both had traveled this path and we're still on it after all that time. I mean, don't you find that a lot of people are reluctant to admit that they've had a hard time, that there have been difficult stretches?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, you know, I think it has to do, what do you do with difficulty? I mean, I think there's a creative process that can be related to things are difficult. So how do we deal with difficulty as if it's just part of the process? Because it is.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think it is.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I agree. I agree. And I think that's where relationships come in, where there are people that their only agenda is, and I've been fortunate to have people like this in my life, their only agenda is, as mine is with people that I try to help, is, if nothing else, being a sounding board or something that can be helpful, because I think that it can be a lonely place. And I think there's a lot of people that feel that they aren't accepted unless they've achieved what to others is a tangible success. I mean …

Dan Sullivan: Has that ever played a big part of your thinking?

Jeffrey Madoff: No.

Dan Sullivan: No, it hasn’t mine either.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: Why is that, do you think?

Dan Sullivan: Well, because I think it's an internal matter right from the beginning that you're having a conversation with yourself. Status really doesn't play much of my, like I've never belonged to entrepreneurial groups. And what I say by that, I'll give an example of a group that I do play and that's Joe Polish with Genius Network. And the reason, you know, I'm how many years now? I'm 14 years that I've been a member of Joe's group. One of it is because I really enjoy the relationship with Joe. There's two more radically different people you can't imagine. We're doing an Audible project for Hay House. And this is not a book, it's just two people. Each of us has sort of a theme we're working on. And then part of the Audible is you get together and talk about what each of you talk to and what does it have in common. It's about a four or five hour finished project. And part of Joe's is just the horrible childhood that he had. I mean, this is public knowledge and it's published, you know, like mother dies at four, father falls apart every two years, moves him someplace different, gets in with bad people, gets abused, gets taken advantage of, shy, introverted, gets into drugs, everything.

And then I said, you know, I've listened to hundreds of people tell their story. And I have to tell you, I had the happiest childhood you can possibly imagine. I said, I had two parents. I was a fifth child. My parents were both fifth children. It was just seamless. We just got along. I had a lot of conversation with my parents, got taken along with them when they were doing things. It was useful, you know, I learned how to be useful. And I said, I can't think of a single thing from my childhood that is negative that in any way has affected me as I've gotten older. Not true for my siblings. I have six siblings. Not true for them, but true for me.

And so Joe told his story, I told my story, and I said, what it shows you, and Joe, you're a talented, successful, ambitious entrepreneur, and I'm a talented, successful, ambitious entrepreneur. So it just shows you, you have your choice of what kind of childhood you want to have before you become a talented, successful entrepreneur. You had a miserable childhood, and here's what has happened to you. I had a happy childhood, and this is what's happened to me. So if you're going to be a talented, successful, ambitious entrepreneur, you have your choice about what kind of childhood you'd like to have.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I think that, you know, people say, well, you know, you work with these models and you work with actors and aren't they just crazy? Aren't they difficult people to deal with? And the answer is no more than the general population. Went to some large insurance office, you'd have people that had addiction issues, bad relationships, et cetera, et cetera. And it's just that you don't know who they are. But if there's a famous name associated with it, a lot of people are very, you know, like the salaciousness of hearing about people who have hit the wall in what appeared to be an otherwise privileged life. And I think that, you know, so I was being interviewed, somebody said, well, so doesn't creativity really come from a positive place? Not necessarily. You know, you can have a miserable life. Van Gogh didn't have a great life, but the pain and exclusion that he felt made his paintings, like Egon Schiele made their paintings incredibly expressive and personal. And that was a result of difficult times. And there are other people that had, didn't have difficult times. And they did really wonderful things. I don't think there's any one input that determines an output. You know, I think it gets to be that black box that airplanes have, we sort of all have it up in here someplace.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I think that, you know, what it reminds me, you know, that I don't think you can train someone to be an entrepreneur, okay, if they don't have the commitment, obsession and perseverance.

Jeffrey Madoff: I agree.

Dan Sullivan: But that would be true of baseball players. That would be true of painters. That would be true of investment bankers. You know, that would be true of anybody. I do think there's a liking for a certain type of activity where you're directly relating to the marketplace that does make an entrepreneur. Most people don't want to have a direct relationship with the marketplace.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think most people don't want to expose themselves to pain or hurt.

Dan Sullivan: Rejection.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. Yeah, that's right. Which is inevitably gonna happen.

Dan Sullivan: Well, if rejection is not a learning experience for you, you're going to try to avoid it.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right, or numb yourself to it.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I find rejection an interesting experience.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I mean, nobody likes it. But I think that, can you learn from it? Yeah, and sometimes you can also learn what to avoid.

Dan Sullivan: Which happens when you get to between 40 and 45.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. I mean, hopefully we've gained some wisdom, you know, during that period of time. So I agree with you, but I think that there is a tendency among people to want to really categorize things and make it a neat little box of if you do X, Y is the result. And if I'm trying to sell you on some kind of a program, you know, my job is to convince you that if you buy what I'm selling, it will have the desired effect that you want. And, you know, you not joining any entrepreneurial groups, you know, that kind of reminds me of the Groucho Marx's statement, which I feel the same about myself. You know, I'd never join a club that would have me as a member. But I think that it's interesting because I think that entrepreneurship, there are those characteristics, as we've talked about, perseverance and the ability to deal with rejection without it destroying you. Doesn't mean it doesn't hurt. And do you always learn from rejection or failure? No. Other than sometimes you'll learn how to avoid it and sometimes that learning how to avoid it has to do with how to think smarter about what it is you're doing so you, as they say, you don't make the same mistake twice.

Dan Sullivan: The big thing that hasn't changed since 1974, because I checked it then, and I check it five or six times, and the actual percentage of people making their living through entrepreneurship was 5%. In 74, it's 5% today.

Jeffrey Madoff: Interesting.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. It's 5%.

Jeffrey Madoff: It's just 5% of a larger number.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, 5% of a larger number. So there are more of them, but their percentage is not higher.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes, yes. Delusion.

Dan Sullivan: I think the reason is that the general economy doesn't need more than five new things to keep the system going.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I don't know. That's an interesting proposition.

Dan Sullivan: I mean, it's a weird thing, but when there's a certain number of people, one of them's going to be a genius and one of them's going to be an idiot, you know. You know, it's relative to each other, so it's … my sense is that to have a certain number of consumers, if you have a certain number of consumers who are buying new things, you only need a certain percentage of people who are creating new things.

Jeffrey Madoff: Makes sense.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, yeah, yeah. And then there's all the people who are what I would say social entrepreneurs, status entrepreneurs. They're kind of entrepreneurs, but it's mostly for social and status purposes. They're not really entrepreneurs.

Jeffrey Madoff: Or they were fortunate enough to be born into enough money that they can kind of appear to be entrepreneurial, but they don't have to think about the same things.

Dan Sullivan: You can be a millionaire today if you inherited $10 million back then.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right. If you haven't spent it all. Thanks for joining us today on our show, Anything and Everything. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend. For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

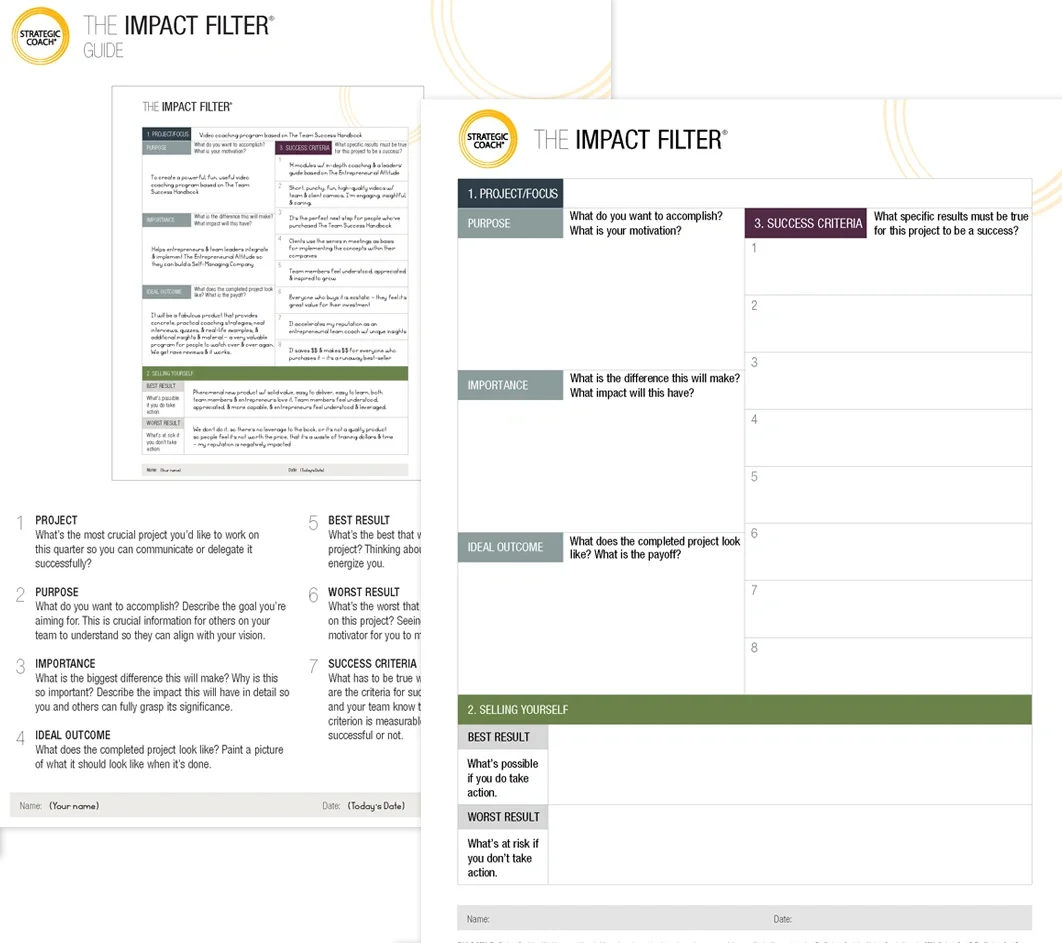

The Impact Filter®

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.