How Childhood Has Changed And What It Means For Entrepreneurs

August 12, 2025

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

Do today’s kids miss out on the lessons learned from early work experiences? Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff reflect on how childhood roles, from farm chores to paper routes, shaped their entrepreneurial instincts. Discover why hands-on work mattered, what’s changed, and how modern entrepreneurs can cultivate resilience, responsibility, and adaptability in a screen-driven world.

Show Notes:

Children today are rarely seen as contributors in the present moment; the focus is on their future potential.

Many traditional childhood jobs no longer exist.

Big social centers, like soda bars and department store lunch counters have disappeared.

Dining out was once reserved for special occasions.

Shared family meals at home were a cornerstone of daily life.

Private transportation isn’t just convenient; it communicates status.

We’re more isolated than ever before, except for those who prioritize relationships.

The true impact of change often reveals itself years later.

Today’s entrepreneurs achieve success earlier than past generations did.

In the past, your first job could easily become your lifelong career.

The competition for your attention has never been more intense.

Resources:

Learn about Strategic Coach®

Learn about Jeffrey Madoff

Bill Of Rights Economy by Dan Sullivan

The Bottomless Well: The Twilight of Fuel, the Virtue of Waste, and Why We Will Never Run Out of Energy by Peter W. Huber and Mark P. Mills

Episode Transcript

Jeffrey Madoff: This is Jeffrey Madoff, and welcome to our podcast called Anything and Everything with my partner, Dan Sullivan.

Dan Sullivan: We were reflecting on something since Jeff and I were born in the 40s and grew up in the 50s and 60s, childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood. We were just reflecting on what's changed and probably along the line we'll hit on some things that are exactly the same 60, 70, 80 years later. And when you asked me the question, Jeff, one thing that came to mind, I think the role of children is very, very different today than it was in the 40s and 50s.

Jeffrey Madoff: How so?

Dan Sullivan: Well, first of all, if you were a child on a farm, you were a valuable piece of labor, you know, that you worked, you know, and you were free labor. And you were kind of free labor, too. Cheap labor. I don't know if you were free, but you were cheap. And that, you know, it was very clear to me at a fairly young age, before six, that there were things that I had to do every week. You know, in my role as child number five, there were things that I had to do to make the household work, to make the farm work. And children had a different role. Today, I think children are not seen as useful in the present. I think they're seen as, they have a great deal of meaning, but I think the meaning of what children are for has really changed.

Jeffrey Madoff: It's interesting because when you talk about what they are for, it implies a certain utility.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: And I'd be willing to bet that on small family farms that those kids are still learning the chores that are necessary to help the family out and help the family business out in that small firm. I wonder if that changed so much.

Dan Sullivan: Well, I think the farms are far more automated. Even the small farms are far more automated than they were then. The other thing is that I'm not sure, at least in the American context, that there are that many small farms.

Jeffrey Madoff: I didn't research that. I don't really know. But I would imagine, however many there are, that the child's roles and that are probably not unlike and what you experienced, but there were other things that have totally gone away. And I think back to when I was, let's say 10 or so, what was the world like? I think I was probably 14 or something, and I had a paper route, and I think you had a paper route too, didn't you? And I remember when we talked to Kathy Ireland.

Dan Sullivan: That's after we moved from the farm. We moved into a town and I had a paper route. Kathy Ireland was the top paper person. I don't know if they called them paper girls in those days or not, but she won the prize as the top paper person. I think she was near Santa Barbara, Montecito or that California just north of Los Angeles. And she was telling us about the paper route.

Jeffrey Madoff: And the thing is that those don't exist anymore. And that job, I mean, what I learned.

Dan Sullivan: I would say jobs for children have disappeared.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, well, I know there's still the summer jobs that kids do, whether they're college kids or high school kids or whatever. What I don't know anymore, like I made money in the summer, I mowed half a dozen lawns in a neighborhood every week.

Dan Sullivan: Me too, I did that.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I don't know if that still exists, because I'm sure that not everybody that's got a kid uses a landscaping service, but you could pay a kid probably. What was it in our day? I don't even remember. Was it, you know, making two and a half bucks to mow somebody's lawn or something? I don't remember.

Dan Sullivan: When a dollar was a dollar.

Dan Sullivan: Yes.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's changed. Yes. As Groucho Marx says, what this country needs is a good five cent nickel. But when I think back to when I was a kid, I think three times a week, the milkman would come. I lived in the suburbs, I didn't live in the country. I lived in the suburbs in Akron, Ohio, and we had a guy that delivered eggs, probably from a small farm. Eggs and milk and glass bottles. I remember when my dad one time forgot the keys, I was probably five, and I was small enough when he lifted me up to go through the milk box so that I could get in and unlock the door. You know, milkmen don't exist anymore. And that would be the first truck you'd see in the morning on the street would be the milk truck, and then he'd carry his metal crate that had the eggs and, you know, what you normally bought with a few other things you try to sell.

And that doesn't exist anymore. Paperboys don't exist anymore. Retail stores, the ones that we grew up with, Woolworths and Kresge's and Sears, don't exist anymore. And there have been a number of major shifts. I mean, I remember when I started writing years ago, one of the things that I really wanted to get, and which I eventually did, was the IBM ball typewriter. That was the height of technology at that time. You didn't have keys, you know, crashing together anymore. It's electric. And it was great, right? You know, it was really neat. And when you got an important communication, when I was Bar Mitzvahed, I got telegrams, you know, and telegrams were like, it was always something important. Somebody had a baby, somebody died, somebody, something.

And I think it was 2006, Western Union delivered their last telegram. And I think of, you would take a picture, you'd have to take the film, you'd have to put it in a box, you'd have to mail it or drop it off at Gray Drugstore in Akron. And then it would be usually a week and you'd get the pictures back. And, you know, in 2012, Kodak went bankrupt. Shortly thereafter, it was, I don't remember if it was right before or right after, but Polaroid followed suit pretty soon. Well, these things that we preserved memories with weren't carried around on our phones. You know, it was, film was the capture. We sent it out to be developed.

Dan Sullivan: Drugstore, oftentimes it was a drugstore that handled that.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, that's right. That's right. And all of that's gone. Including the soda bar at the drugstore. And Woolworth's had the lunch counters, you know. And the Five and Dime.

Dan Sullivan: Those were big social centers.

Jeffrey Madoff: That’s right. Well, that was the, like Starbucks calls it now, those were the third spaces. You know, you would go shopping and it was a big deal. We went from an individual store, there was department stores, then there were shopping centers, and then the enclosed shopping center, which was a shopping mall, which those of all, you know, at the time, those were innovative concepts, which are no longer. So I was thinking about what are the things that companies that lasted had in common? What are the common threads of those that didn't make it or switched? Now everybody's, you don't need a camera unless you're a real enthusiast, because most likely you have a phone. You can use that. So there's been major shifts in just day-to-day things.

Dan Sullivan: Along the lines that you're talking about is eating out was a rare occasion, especially dinner.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think

Dan Sullivan: You ate at home, you know, right. And the road to that really started with television, where they came out with TV meals. It was a frozen meal, and you could…

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes, Swanson’s TV dinners.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, you could heat it up. I remember I caught a statistic two or three years ago, and I think COVID had something to do with it. But that year, it crossed 50% that people would eat their meals out. I can't remember my childhood. Of course, I grew up on a farm and then I grew up in a small town. But I can't once, before I was 18, ever remembering going out to an evening meal, a dinner meal with my parents, except for a special occasion. It was a wedding or it was a function at the church or something like that. But you ate your meals at home, you know, and that was a big part of family life.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I would imagine it was also different for your family, because going out to dinner meant you had five kids, you know, along with the two parents.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And we were seven at the top.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. So, you know, that's a lot of money, you know, for, you know, working class people to spend. And I suspect there were shifts when places like McDonald's, initially McDonald's, where you get a hamburger for 15 cents when they opened, and you could feed a family of seven for probably under $5 at that time.

Dan Sullivan: Different dollar.

Jeffrey Madoff: I'm sorry?

Dan Sullivan: A different dollar.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. But it was still, it was relatively cheap regardless. And the thing that has happened, I mean, to put it into a big context, I think when I was reading and doing research on change, technological change, and how that affected our culture and so on is, I was thinking, how can I sum this up? And it went from a physical life, if you will, to a screen-based life. You didn't have to show up. You didn't have to show up to buy things anymore. You could do it online. You didn't have to show up at the video rental store, even when things came along that far. Netflix was smart. They started off when you were still renting physical discs, but they gave you the envelope to send it back. What could be easier? It killed Blockbuster. And of course now you don't have to have any inventory of physical goods.

Dan Sullivan: And you don't have to go to a physical place to see movies.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right, that's right. And you don't have to go to a physical place to rent movies anymore. And so I thought about that, let's call it de-physicalization, where you didn't have to show up anymore. And what does that do? And how does that impact on us?

Dan Sullivan: Well, I think it cuts down on a certain amount of social contact tremendously.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I think tremendously. I think you're right.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. It's very, very interesting because there's a growing number of our clients in Strategic Coach who have their own planes, you know, and they have timeshare and they have other aspects of them, you know, they have partnerships and they own jets. And I've gone several times, I've been invited to fly, you know, and it's enjoyable, but I actually enjoy going to the airports. I actually like being in a situation, I like going to train stations, you know, I like, and it's just watching all the different kinds of people that are showing up. And I don't get that same feeling when I fly, I go to a private airport, you know, I take a limo to a private airport, I get out of the limo, you're met at the doorway of the limo, and you have to check passports.

And then at the other end, it's the same thing, you get off the plane, and there's a limo. And it would never become attractive enough for me that I would ever have a plane. It just wouldn't interest me. And, you know, I find it interesting. And the other thing is that I've arranged my schedule so that I really don't have to. You know, I mean, we have trips to Chicago. We have eight weeks a year in Chicago. I have a week in London. And, you know, and that's about it.

Jeffrey Madoff: My authorities had to also.

Dan Sullivan: Well, that's medical, so that's different, but it's not a business thing. So it may be just the life I lead. It's not a requirement. I know people are flying for business every week. You know, they're doing something. And one trick that interests me, it's a little off topic, but our context for the podcast allows for a little bit off track. But they have business meetings where they find out where a customer is going and they'll fly the customer to them and they have a captive audience for seven or eight hours on board plane. And the guy is, it's a sort of treat to fly the person where he's going. And, but you got a captive audience, you know, you have a totally captive audience for three or four hours, you know, and you have their full attention. And it's kind of an interesting technique, totally impossible in the 40s or 50s, you couldn't do that, but you can do that now.

Jeffrey Madoff: Of course, the person who agreed to take the flight, hopefully they're aware that they're not, this is a transactional relationship. But I think, you know, there's no denying in that scenario, there's also the presentation of status. You know, I'll have my driver pick you up, we'll bring you to the private plane, we'll fly you there.

Dan Sullivan: It kind of has all sorts of messages.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes, exactly.

Dan Sullivan: It has all sorts of messages.

Jeffrey Madoff: But you know, when we were kids and we had our paper routes, I don't know how many, I don't remember, but let's just say that there were 75 people I delivered papers to in the neighborhood that I served. So those are 75 households that I would not have met otherwise. Those were 75 opportunities once a month when I collected money that I had to learn how to have an interaction and engage people that I wouldn't have had.

Dan Sullivan: The other thing is you had to pay for the papers before you sold them. Before you delivered them, you know, you had to buy the papers. And then you had to make money on inventory.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. And so, you know, that's when I kind of learned, I actually learned it from my parents because I had retail stores, but it was, I was buying, whenever I had my paper out, 12 or 14, I was buying wholesale and selling retail. But I'm more concentrating on the socialization aspect of it. You had to show up at the person's house to get paid. And yeah, that was another thing that happened to during our lifetimes is credit cards. I think credit cards happened in like the early or mid-fifties is the first I used to be when you bought retail, you would buy, put things on layaway. which means they laid them away on a shelf until you paid for it. You couldn't take it, but you could pay for it over time.

Dan Sullivan: Before you got it.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. And I, the other day I bought a new pair of shoes and there's this shoe store near me. And, you know, New York's a walking city. So I like that, like, off the bat. You know, you and I have been talking on the phone, there'll be an interruption because I just bumped into somebody, you know, and I love that kind of thing. But I think that one of the main things that I think that we're losing is that live interaction in real time with people who are in the same space that you're in.

So, you know, we've talked about this before, we're more interconnected technologically than ever before, yet we are more polarized than ever before, and more isolated than ever before, unless you make an effort not to be, which I do, which you do, and the nature of the work we do helps prevent that. But I think there's something really fascinating that between our phones and our computer at home, how it's mitigated necessity of showing up in any physical way to do the vast majority of things that you do. You know, I think that's fascinating because we still don't really know the impact of that.

Dan Sullivan: Well, I wonder if you ever do when it's happening. I think impact is something that's noticed long after something's happened, you know? I mean, nobody really knows the society that's happening right now because it's using up all your attention, just moving. I think it's very hard to get a big picture of, you know, I see the 40s and 50s as significant when I look back, but I didn't experience that while I was living through it. It was just day to day.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right, yeah. But you know the fact that you and I do this every week, we were, we both draw from different perspectives and where we coincide is our curiosity or intellectual and creative restlessness and all of those kinds of things. We might be divergent on other topics in other areas, but there's a true exchange that goes on between us that you know, I'm not gonna speak for you, but I feel there are benefits from that. And that's why I look forward to this every week, you know, that I'm engaging with someone else in an interesting way.

And this is a good example of the technology because it enables us to look at each other, to see each other. Again, we're not in the same physical space, but I think that interaction with different, new, or challenging ideas is something that happens less because we're talking to fewer people for the most part. I'm speaking as a generalization, but I think people are interacting with far fewer people than we interacted with.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I think that's very true. I mean, I live in a world where I meet lots of different people, but they have one common trait and they're entrepreneurs. Like, you know, if I went out, you know, from the center of where I live, that virtually everybody I interact with, say in a year's time, with the exception of family members. And the family members of my team, you know, I meet husbands, we meet children. But at the core, and I think it's what the common ground for us starts with entrepreneurism. Yeah, I think, I mean, we don't have any friends who aren't entrepreneurs.

Jeffrey Madoff: Are you talking about you and Babs, or?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, you know, because it's been 50 years since we started coaching entrepreneurs, so, you know, I mean, first of all, it used up a lot of time, so the time was spent with entrepreneurs, but then you get to know, I'm getting third generation people in Strategic Coach now, that the grandparents were clients in the 1980s, and then the parents came in in the, say, you know, the 2000s, and then their children now are showing up, you know, The one thing is that what we're noticing, and this is a change just in terms of our own client base, is that the entrepreneurs are getting more successful at a younger age, just in terms of money making, than was true 40 years ago.

Their grandparents, it took them a long time to really become successful because a lot of the entrepreneurs now are using technology to get successful at a much younger age. They don't have paper routes anymore, but they're designing websites. They're doing all sorts of technological kid’s jobs that they can. I know you've met Shannon Waller, and Shannon's daughter was doing really good websites when she was about 15 or 16 years old. She's about 25 now, but she was making money setting up websites when she was 15 or 20. And so it'd be interesting to see how many children are still working, but not in a way that we would recognize as working.

Jeffrey Madoff: When we were young teenagers, as we said, we had paper routes.

Dan Sullivan: Paper route, mowing lawns. I was a caddy. I was a caddy. I made a lot of money caddying. Never saw the reason for playing, but I saw the reason for playing.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I was a greenskeeper at a golf course.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: So we, we check out three things. And I never had an interest in playing golf, but I did have an interest in having a job that summer. It paid me. So yeah, it's interesting, but you know, I still see here in New York, kids with a little table selling lemonade and chocolate chip cookies on the sidewalk. That was happening back when I was their age. You know, that happened. They had a lot more foot traffic. They had better location for sales than I did in Akron. But, you know, there was that. But, yeah, on one hand, a lot of the barriers are down. If you're a bright, savvy kid and you've got, you know, I mean, Audrey was doing graphic design and being paid for it, you know, when she was in early high school. You know, when she was like a freshman, she was. I don't know, I guess that's the mowing the lawns, you know? I mean, it's, their technology has allowed you to be more ambitious.

Dan Sullivan: Well, it's interesting because there's a trait among the entrepreneurs, especially, that they were into making money for useful work at a much earlier age than the general population. I noticed that.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I know my motivation was that there was stuff that I wanted to buy and just things that money always meant to me at level of independence.

Dan Sullivan: Well, it's freedom.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, it's freedom. And so I like that, although I can also honestly say that I was never fixated on money. Now, maybe that's because I've been fortunate enough to be able to do the various careers I've had. I've been fortunate enough to make money doing it.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: But yeah, I think that those jobs have definitely changed and the ability to, I hate the term, but scale when you're online and doing things, you can, you know, there's those opportunities that I guess we have seen that there are young people that can do very well and without any advanced education can do well. But I think there is, you know, there are other things that happen along with that.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and the other thing I think, I remember first grade, 1950 was first grade for me. We had all nuns. I went to Catholic schools for 12 years. I remember Sister Mary Josephia, she was my first-grade teacher. And she says, the reason why you're learning this reading, writing, and arithmetic, basically, is that when you graduate from high school, this is why you're going to be valuable. And in 1950, that was a good prediction, that in 1962, the things that you had learned during the 12 years really had immediate applications. Reading, writing, and arithmetic were required, unless you were doing manual labor, and that didn't really appeal to me.

And I got it in my mind that using your brain was more valuable than using your body to get paid. I caught that very early, and I'm still doing it decades later. It's my brain. So I think there's a difference. There's probably a fork in the road, as Yogi Berra said, when you come to the fork in the road, take it. But there is that, are you going to get paid just doing what someone else has designed for you? Or are you going to be part of the designer of why you get paid? And I think there's a real, that's a real separation. You can do that a lot better today than you could in the 1950s.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, well, I think so. I mean, it's also, you know, when we were growing up, you could get a job that would be the job for the rest of your life.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: I think that started going away.

Dan Sullivan: That's a huge change. That's probably one of the hugest changes. It was, you know, there was management work, but it was very high up, but mainly you were just doing jobs that other people created the jobs for you. And you were showing up every day and putting in the time. I think that there's been a change in what work means. Actually, I'm including this in my section, that there's many ways that people want to get paid for work in addition to money.

In the 1950s, if you had a job, that was the purpose. You didn't have to like the work. You know, the whole thing that work should be enjoyable and it should be fulfilling and it should have meaning, I think that that's been a creation of recent times. I don't think that existed in the 1950s. And before. Because you had the history of The Depression 20 or 30 years previously. You know, a lot of people wanted to go into the military when the war started in 1941 because you got three square meals a day.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, well, you know, and when the draft went away, and there were all these fears about who you would end up with in the military, they've actually ended up with better people because they wanted to be there.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah, you know, it was very interesting. I had a cab driver in New York City and he was a military vet, but he was an illegal immigrant. And he went down to a recruiting office and he said, if I sign up for the army, will I become a citizen? And the recruiter said, absolutely. And I wonder if that still exists, that there's a lot, because the percentage of the military today is Hispanic. It's mostly Hispanic. It's over 20 percent, much higher than the Hispanic population.

The military has more Latinos than it has, I mean, whites are still tops, but when I was in the Army, there was a saying that if you had a sergeant or an NCO, non-commissioned officer, or you had an actual commissioned officer, and he was black, it was going to be better than the white NCOs and the white officers. And the reason is that he couldn't work for IBM, he couldn't work for all the big corporations, so this was the career path for a lot of blacks. Mine was 1960s, and I had great sergeants who were black. Who would be an executive at a corporation if they were white?

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, there are so many factors involved. And, you know, the thing about being an entrepreneur is you're creating the opportunity as opposed to being filtered out of that opportunity for racial reasons, gender reasons, you know, whatever.

Dan Sullivan: And I think it has to, creating value before you expect to get paid is actually a mindset that's very, very different that really separates out the populations. One of the early workshops, there's two decisions you have to make to be an entrepreneur. One is that you're going to take complete responsibility for your financial future. That's the first decision. And the second thing is that you have to create value. You have to make a value proposition before you're going to get paid. Yeah, and we did this with the book. You do this with the play. You have to create the value before you get paid for the value you've created.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I mean, as an entrepreneur.

Dan Sullivan: As an entrepreneur, yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right.

Dan Sullivan: I think it's a radically different life. I think being an entrepreneur is just a radically different life than any other way of making money and making a living in your life.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I think, you know, it's so funny because of my parents, as I mentioned before that, you know, my sister has her own business. That was just what you did.

Dan Sullivan: Yep.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, so nothing was unusual to me about it, wasn't like, wow, you're going to start your own business. I didn't think of any other approach to making money. Starting something I wanted to do.

Dan Sullivan: And that's exactly the same today as it was 70 years ago. It's just a lot easier. There are a lot of different kinds of businesses you can create today.

Jeffrey Madoff: But I think that part has always been true. There's a lot of different kinds of businesses, but I think that one of the big things that's different is the cost of entry into businesses. Years ago, there were many more barriers.

Dan Sullivan: And a lot of it was just years that you had to put into actually getting there.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, the years you had to put into getting there, yeah, but it was also then you were stuck with, I mean, we're going through it now in terms of office space. You know, if people don't have to show up, you don't need huge office space. And, you know, there's a ripple effect on all of that. It affects the local businesses that used to eat lunch or, you know, buy things in that neighborhood. I mean, there's all kinds of ripple effects on all of that sort of thing. And when business is conducted online, you don't have those same restrictions. I think there's other costs.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. But when there's trade-offs—that’s the third rule, is for everything that you get on the plus side, there's a trade-off on the negative side. And you have to realize that that hasn't changed. It's, the question is, do you know what the trade-offs are?

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, when I spoke about in previous podcasts, the Stanislavski method. That's the first thing in terms of analyzing a character's motivations is the given circumstances. And do you understand that? Just like there's, people would say to me, people who are entrepreneurs who are talking about their financing that they're getting, and they wore that money raise as a badge of honor. And I thought, I was actually talking to Dame and John about this, and I said, you know, to me it's debt. You know, you're building up debt. And …

Dan Sullivan: There's a change.

Jeffrey Madoff: What do you mean?

Dan Sullivan: 1950s.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. In terms of …

Dan Sullivan: Taking on debt.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. Well, so not surprising that that's when credit cards started. You know, it was another form of debt. Seemed painless because you weren't really, it's the same psychology used in Vegas. You don't use actual money, you use chips because it doesn't seem as real and the consequences isn't as real.

Dan Sullivan: And also you'll never see a clock in Las Vegas.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right.

Dan Sullivan: You'll never see a calendar in Las Vegas.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right.

Dan Sullivan: It's not really money and there's no time.

Jeffrey Madoff: That’s right. Until you leave.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, it's so funny. We had a function in Las Vegas and we were staying at the Four Seasons. And it's half the building, the other half of the building is Mandalay Bay Casino. And it's very interesting. You can walk from the Four Seasons to the casino, but you can't enter from the casino into the Four Seasons. You have to walk outside, walk around the block and come in. But Babs and I, we had time to walk. We were going to the Venetian, which is, you know, it's about a half hour walk from the Four Seasons. And it was very early. It was like seven or eight in the morning. And we passed by the slots and there was a newly married husband and wife at the slots. She was in a wedding dress and he was, you know, he had a tuxedo on and they weren't paying any attention to each other. They were both at the slots and we got by them. It wasn't crowded because it was early in the morning. And I turned to Babs afterwards and said, I don't think this is going to end well.

Jeffrey Madoff: I love that image that I got of her and her wedding dress and him in a tuxedo playing the slot machines because it became a metaphor for life. You know, that image.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, yeah. And possibly they met each other five days ago.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right.

Dan Sullivan: And they got married. And you can get married 24-7 in Las Vegas. There's no problem with that.

Jeffrey Madoff: And divorced.

Dan Sullivan: And divorced, of course, yeah. But it's interesting. So what we're saying, there's been a real fundamental change of time, how we treat time. Because debt is a totally different attitude toward time. Everything related to morality and ethics is related to time, that what you're doing right now is gonna have future consequences, and I think when people lose a sense of future consequences of present actions, I think their life goes in the ditch.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, no question. I agree. But the interesting thing also about time in businesses is one of the major changes is it used to be something special to get something overnight, and expensive. I mean, you know, Federal Express, which isn't federal, you know, that's just the name of a business.

Dan Sullivan: It is express, though.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes, yes, they're half-truths, yes. Yeah, just like, you know, United Parcel Service. You know, it's not United, it is a parcel service. And, you know, if it absolutely, positively has to get there on time, you know, that was their, well, that's Amazon slogan, in a sense, you know, slight iteration on that. Most things that we get, do we need them delivered that fast?

Dan Sullivan: We don't.

Jeffrey Madoff: But all of a sudden, not all of a sudden, but pretty quickly, that became a thing. I was talking to somebody and they said to me, they love shopping online, they can order from Amazon and they can get it the next day. And I said, like what? They said, well, I was gonna get this pair of Nikes and order them from Amazon, got them the next day. And I said, you know what? I walked into the Super Runners store. I was able to buy them and walk out with them. Just like that. Magic. You know?

Dan Sullivan: So there's been a profound change in time.

Jeffrey Madoff: And our perception of it and the importance of it. Because I would be willing to bet that the vast, vast majority of things, you don't need that quickly. You know, I mean, putting aside medical issues, things that you have to get that are life or death immediately because of some extraneous, extreme situation, you know, did you really need to get the paper towels, you know, that quick? Plan better.

Dan Sullivan: Well, there's a big thing about planning and investing. Yeah, you know, I went to college very late. I was 23 when I had been out in the marketplace. You know, I'd had a job right out of high school with the FBI. I worked for the FBI for two years. And it's very interesting. There's a set of events here. When I was 10 years old, Sports Illustrated had more or less just started. And there was an article when I was 10 years old in Sports Illustrated about a program called Outward Bound that took place in Britain. It was created by Prince Philip, actually. And the reason they did it actually had to do with the Merchant Marine in Great Britain. They noticed the Merchant Marine in the 1940s, partially the war, but Merchant Marine after that.

They found if there was an accident at sea, that the older sailors survived and the younger sailors drowned. And they said that the older sailors had gotten accustomed to adversity. They had gotten accustomed to emergencies. But the young people, when confronted with a disaster, weren't able to respond. They got isolated rather than went to teamwork. The older sailors went to teamwork right away and the younger sailors— so Prince Philip and his schoolteacher, actually a man, Kurt Hahn, because Prince Philip was actually from Germany, he was Greek and German. He wasn't British. And so they had a school in Germany where they confronted them with outdoor, very, very challenging outside activities. And they created this hiking and climbing and, you know, but it required a lot of teamwork.

So they created this program called Outward Bound. And they were just in Britain, as I knew it. They were just in Britain. And you spent four weeks. It was a four-week course. And they were mainly teenagers. It was for teenagers. And I couldn't do it. It wasn't something that I could afford. It wasn't that I had time. But when I was 20, I decided to do it. And I quit my job at the FBI and I saved up money and I went off to Scotland in 1964 and I did four weeks of it. And it was really, really interesting because when I got to Britain and I was talking to the British, and I was the only person from Britain, they were from Northern Ireland, they were from Scotland, Great Britain, and there was one guy from Malta, which was a British territory, and they were asking me, well, how did you get here? Who sponsored you?

Because all of them had been sponsored either by a corporation who was sending them for training, or the legal system. They were saying, we're going to send you to this school, and if you don't perform well, we're going to send you off to another school, which is called a jail or a prison. And so I was there, and I was talking to them, and I got a huge wake-up call about how different things were in the United States than Great Britain. And they said, well, you know, you had a job. Now how are you going to get a job? And I said, I'll just go back and get a job. And they said, you quit a job. Then you have that on your record. You quit a job and you came off and did this. How did you do it?

And I said, it's easy, you can easily get a job. And partially it's when I was born, I was part of the generation before the boomers. Okay, so I'm, that was the first generation, it's from the 1920s to the end of the Second World War, it's called The Silent Generation. It was the first American generation that was smaller than its previous generation because there was a drop off in birth rate during the Great Depression and also during the war. Men were away, you know, so you didn't get it. And I said, yeah. And they said, well, who paid for this? And I said, well, I just saved up the money and I paid for it. And, you know, you paid for the flight, you paid for all your lodging. And I was over there for about two months. Part of it was that Outward Bound.

And then they said, what about schooling? And I said, oh, I'll go to university. Well, how can you go to university just like that? And I said, you get a job, you make the money, and you go to university. So then I was in the army. So I was just ready to go back and get another job after I came back. And I was drafted during the first big call up in Vietnam. So, you know, that was two years of my life. And then I come back and I saved up the money and I borrowed money and I went four years of university studying something that had absolutely, you know, at first appearance has nothing to do with any kind of work you're gonna do. You're just gonna study and talk about the great books of the Western world for four years.

But then, you know, I met somebody who ran an ad agency in Toronto and he was fascinated with my education. And I had also created the school newspaper. They never had a newspaper because I wanted—first of all, the army taught me how to type, which was a great skill. And I learned because I was a chaplain's assistant and you had to be a secretary. You were a driver. So I came out of… and then I had been an entertainment coordinator in the army, so I came back. I had the GI Bill that paid all my living expenses, and then I borrowed the rest of the money, and I paid it all back in about six or seven years. I paid all the loans back off.

But the big thing is that I had, in both the things, I was looking at Outward Bound when I went Outward Bound, is learning these skills are gonna be lifetime skills. When I went to The Great Books College, I said, knowing all where the ideas come from is going to really, really help me later on. So you have to have a sense of future payoffs that are long before you get to them before you do it. So that sense of I'm doing certain things now, that's a down payment on a bigger future.

And I think that's the thing that really varies between people, that you're doing investing now so that you get a payoff later, not so much like a financial. Well, financial investment would be the same thing. And that's the one thing that I feel I didn't do well in my 20s. I didn't really invest and save, but I think that there's the how people treat time really makes a difference about whether they can see a future that's worth investing in now.

Jeffrey Madoff: First of all, I want to congratulate you because you and our anything and everything examples each week came back to the sense of time. That was good. That was really good.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I could feel the stretch, but then I had to come back to this. You always have to go back to the middle somewhere along.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, that was an impressive get.

Dan Sullivan: Where is he going? Where is he going? Getting close to the cliff. But the whole thing is that I've always had this sense of time, you know, that if you do things right right now, they have a multiplier effect in the future.

Jeffrey Madoff: But I also have to believe in knowing you, as I think I do, if you weren't interested, no matter what the payoff was, you wouldn't do it.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: So prior to the hope for that investment to growth, so to speak, through knowledge and everything—and correct me if I'm wrong, but I think the initial seduction is this is something you found interesting.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: It wasn't like I'm going to deal with something.

Dan Sullivan: No, no. There was no … and do you have enough money in the present to actually pay for this experience that you're interested in?

Jeffrey Madoff: But, you know, when you went through your bankruptcy, since that time, and I know you also credit Babs for this. You know, that you can pursue what you're interested in and that pays off. Same thing I've done. Because I can't claim to have had the foresight, you know, if I start making films, I can make money doing that. And no, it's because I was interested in making films, it's because I was interested in writing a play, because I was interested in design, I was interested in teaching. And that's why I did it. Because I think it all gets difficult if you're not really interested in it and you're doing it for something else.

It's like exercise when you get no results. It just becomes a drag routine to have to do it. And then life goes downhill from there as you're doing stuff you don't really want to do, but you feel it's necessary to do in order to make a living. And I think that's a big part of it that is often overlooked is, what's your real motivation for doing what you do? Yeah, because I also think that's another conversation. But I think that one of the things that has happened as a result of these changes, because many businesses need initially less of an infrastructure than they used to need in terms of the start-ups and the proliferation of start-ups, it's easier to get your message out, hard to get it in front of people's eyes because there's so much stuff.

Everybody knows they can go online, they can be seen everywhere, but you gotta be a savvy marketer and somehow capture the attention in order to do that. But I think that the less we physically show up, the less that we are together physically as people, because this to me is the supplement and the complement to in-person times, where that in-person time is really great. And this reinforces that, because we can't get together physically that much as often as we do this, but we do this and it enhances the overall relationship. But initially, the first few years that we got together, that was only in person. You know, it wasn't this.

And so what I think about is there was social glue that happened in showing up to the workplace, in walking into a retail store, in walking the grocery aisles, whatever it is, where you bump into people, where you interact with people and so on. And I think that the same thing that has allowed these opportunities, that flip side is that that glue that holds us together has diminished tremendously. And that's the thing probably that concerns me the most about this. Because when I look at the times we grew up in, I'm not claiming they were the good old days at all. What I am saying is that there were virtues to social interaction that we have lost as a result of what's happening.

Dan Sullivan: Well, there's a challenge that can be overcome. In other words, you have to be aware that something went missing before you can create a new solution to it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Before you can look for it.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, before you can look.

Jeffrey Madoff: I used to love what people would say. You know, I found that the last place I looked was, well, of course you found it the last place you look. Why would you keep looking?

Dan Sullivan: That's where you found it. One of the exercises I do with the entrepreneurs is I say, really big projects, how long do they take? And, you know, for example, in financial services, like really high-level life insurance, It can take two years before you're paid for all the work that you do to put it in place, and it's risky. And they said, you know, these big cases, they take two years. And I said, actually, no, the sale is instantaneous. It was not getting the sale that took all the time.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right.

Dan Sullivan: It's like learning. They say, well, you know, learning takes a long time. I said, no, it's the non-learning that takes all the time.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right.

Dan Sullivan: It's true. You didn't get it. You didn't get it. You didn't get it. And then you got it just like that. And you said, oh. why didn't I get it right away? And I said, well, some getting it takes a lot of not getting it before it actually …

Jeffrey Madoff: And there is the work that needs to be done. And a lot of people don't realize the realistic hill that they're climbing and how steep that can be. You know, when I think about, well, it's even here, but in Akron, and my parents were one of the first tenants in this new shopping center. And that shopping center was the Woolworths that had the Sona Fountain and all of that. And I think of those stores, none of which exists—I mean, Wooler's main competitor was Kresge, which became the K in Kmart, which has also gone out of business. But what are the evolution of business and how businesses grow and then how they fail? And I think a lot of the thing about the failures of business that were household names like Kodak, Kodak actually had a division that was doing digital film, digital image capture, I should say. But it was underfunded, although they had completed a successful model, but management there was in denial because the margins were so high on film that they didn't want to think about it.

Dan Sullivan: You can just see the guy who innovated that showing up at the board of directors meeting. He says, guess what? In the future, we don't have to create any film. And their entire payoff for their management career is how much film has been. Well, you know, the graphic user interface was created by a guy at Xerox.

Jeffrey Madoff: Xerox partners.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: So, you know, think about where all the information is now. It's not just on the hard drive of your phone or your computer. All these things in the cloud, how available all this stuff is, how you can do pretty amazing things sitting at your desk with AI, a tool that I think I think, God, it's almost overwhelming because the possibilities are tremendous. Potential consequences are devastating. And, you know, are we able to apply the lessons that I think have become so present in ignoring and letting social media run off on its own and the destruction that has caused? Are we gonna learn anything from that? Or are things gonna get more isolated, more individually driven? And, you know, it's like the hammer, you can beat somebody to death with it, or you can build a house with it. You know, how do you look at it? Because, you know, we both enjoy using AI in different ways and in the same ways. How do you look at that? Do you see that as anything to be reconciled on a societal level, like through regulation or whatever?

Dan Sullivan: I don't think it happens through regulation. I would say the solutions come from the attempt to regulate it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Explain what you mean by that.

Dan Sullivan: Well, we don't like being regulated, so we'll create some solution to avoid being regulated. I just finished the book. I'll send you a copy because it comes back from the printer. It's called The Bill Of Rights Economy. And I look at the first 10 amendments to the Constitution, which are called the Bill of Rights 1 through 10, and my sense was that the founders of the country, one way or another, were entrepreneurial as compared to how people make money today. They were merchants, they owned plantations, some of them were illegal, they were smugglers and everything. But there was a sense that in the new world, you had to come up with new solutions from what existed in Europe or existed in the British Isles.

And if you go through all ten of them, and I put all ten of them together, it goes to the first article of the Constitution, it's section number eight, and it says that we have to encourage the consecration of new knowledge and new skills, okay? And therefore, to have innovators and inventors, we have to give them a monopoly for a period of time where they can actually get paid and rewarded for creating new things. And then the 10 amendments all protect that creation of new things.

So there's this sort of dynamo right at the center of the Constitution that encourages entrepreneurism and it's how you're protected from other people stealing your stuff and how you're guaranteed, like the First Amendment, the biggest guarantee of the First Amendment is that people will be talking about anything that they want to talk about, and you don't interfere with that. You know, you can do that. And that encourages commerce, that encourages new ideas, that encourages new things. And so my sense is that I think that the problem that you're talking about is probably much more safeguarded in the United States than it is in Canada, for example. I think it's more guaranteed because they don't have those rights, the rights that are there. Canada really doesn't have a constitution the way that the United States has a constitution.

And it's a very contentious constitution. The fight is going on every day. There's a constant collision. People want to do some things and people say you shouldn't be doing too much of that. So my sense is that regulation, that isn't really accepted widespread. It's your feeling of interference by the government. The biggest difference between Canada, Canada, there's an admiration for government. In the United States, there's no real admiration. It's seen as a necessary evil, but it's not admired.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I would say that up until relatively recently, when we were growing up, going back to that theme, the Supreme Court was respected. And it seemed like this august body, and I don't remember being aware until relatively recently what political party and who appointed who in the Supreme Court. It's not because I was ignorant of that, but it also wasn't so front and center and present in the political discussion as from either side a disqualifier of certain people's opinions.

Dan Sullivan: Totally. In the 1930s, it was with Roosevelt. Roosevelt tried to overturn the entire Supreme Court because they were interfering with his regulations.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, and I'm not suggesting that there aren't precursors to this. And I think it's undeniable that there was a respect for the court and what it was that has changed. I think that there are so many institutions that used to be respected that aren't, for whatever reasons.

Dan Sullivan: Well, I think technology has part of that in the sense that, you know, I think that there's always been technological changes. I mean, it's that they've taken a different form. You know, the rapid industrialization, which destroyed farm life in the 1890s, 1900s and that, you know, there was enormous—I did an AI search, Perplexity, and I said, what are the 10 most polarizing contentious errors of U.S. history? And our present one is rated number 10. Of course, as you said earlier, when you're in it, you don't really know. I mean, we're comparing it the way it was at one time in our life. You know, I mean, we're using our own lifetime as a comparison.

So my sense is that having not lived in the United States properly for 54 years, I kind of think that Americans have a way of sorting things out. There's a big danger and they get a handle on it. Education changes. One of the big things now is the big shift back to skills training. You know, the enormous amount of money that's going back into the trades because we're short of plumbers, we're short of electricians. There's a shifting in what constitutes education and what's seen as the importance of education.

Jeffrey Madoff: I mean, I know where I grew up in Akron, the school I went to was a new school, I was the third graduating class. Firestone. And I think that, I remember you talked about learning how to type. So I took typing, and I was the only male in the class. And the teacher said to me, why are you taking typing? And it happened, my sister was four years older than I am, had learned how to type and she was like making 50 bucks a week typing, which was good money back then, her freshman year of college. People's papers, you know, she had an electric typewriter and she did it and I thought well that'd be good to fall back on, plus it's a more readable paper, but that's a good skill to have.

And I took a class called Senior Problems, which is an odd name for something. But that taught you how to open a bank account, how to balance your check book, how to apply for a job, all these things. And that was considered for the kids who were not on a college track. And so the same thing, the teacher said, why are you taking this? And this is probably the most useful information on get out of this school, is learning how to open up a bank account, learning how to balance my check book, all that sort of thing. And then, of course, the trades, you didn't go to college at all, which in our generation was looked down on, where in fact, what you're saying, you can make a really good six-figure income being a plumber, an electrician, a builder, a cabinet maker, all these kinds of things, you can make a really good living.

And those were overlooked here for so many years as a viable way of participating in the economy, when in fact now, because of scarcity, you can be so busy all the time if you're any good at it, and you're right. And I think that was part of just, I think, a status thing.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I think it was an upward mobility. There was a promise of upward mobility. And I remember back in ‘08, ‘09, when you had the economic crises. okay. And it broke a, it was sort of a contract between higher education and the sort of a contract that doesn't matter how much you pay for higher education, it's going to amortize itself later. And I think for the last 15 years, that's not been true. I was reading in December that 40% of the Harvard Business School who had graduated last May and June still did not get jobs. And that's a disconnect. There's a disconnect there that if you go to a really great university and it's going to guarantee you economic opportunity, but it's also guarantee you a higher social status as a result of graduation. And I think that has fallen off. And I think that's creating a lot of the anxiety and tension in society right now.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, yeah. And I think for our age, the thought of after college moving back home, that wasn't even considered.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, no. You know, I was gone five days after I graduated from high school.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. And when my last time living at home was after my freshman year of college, I was home for that summer, although I could do anything I wanted at home. And I got along great with my parents. I wanted to be in Madison where I went to college, Madison, Wisconsin. I wanted to be there because there was, you know, all people my age. And I mean, it was just great fun. It was action. And you know, that was it. But I think with the huge difference from when we were growing up to now, kids in their twenties who have been graduating in the last few years, is it used to be the rule of thumb was one week's pay, one month's rent. Now it's like three weeks pay is one month's rent. And that doesn't include food because rents are so much higher. So I think it's kind of crippling a certain kind of forward motion, you know, just because it's a lot tougher on that level.

Dan Sullivan: Well, I think what's changed is I think that the future is uncertain.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes, I think that's right.

Dan Sullivan: And it always is. But it differs from one decade to another decade.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. Yeah. And I think that, you know, looking at companies that were household names and seemed like they'd be there forever, like Sears, like Kodak, like Polaroid, you know, the typewriters, all these things during that time, who could have imagined that those would all be gone? And that if you looked at the top 10 businesses in the Fortune 500, I don't think any of the companies 25 years ago were still on that list. But it used to be a much more stable list. Year after year, it'd be the same. That's not the case anymore.

So I think it's the ability to adapt and to, I think the ability to adapt and to persevere is huge. But I think it requires a different mindset in order to do that. But I think it's really, really fascinating to look at these changes, some which I think can create phenomenal opportunities, and others because there are always bad actors who will corrupt any system and game any system they can for financial reward. And there are some people that just like destroying systems.

Dan Sullivan: Well, anybody who creates something new is threatening something that exists. I just think that the amount of new kind of innovation in different parts of life has really, really increased in our age. You know, I mean, the population in the U.S. is three times higher than when you were born. There's just a lot more people, you know, in the marketplace and that's competing. I can say it here in Toronto, I told you the statistics, the city has grown three times in, you know, 50 years that I've been here, it's three times bigger. But what it's doing is it's sucking out all the talent.

For example, when you were growing up in Akron, if you drove through small towns between you and Cleveland, okay, there were a lot of small towns, they were viable small towns, but all the talent got sucked out of them. They go to the center city. You were born in Akron, but you live on the Upper West Side of New York. Far, far more opportunity for a person of your skill and your inclination. You'd never go back to Akron. I grew up in Norwalk. I'd never go back to Norwalk. I'd go back and it's kind of interesting to walk around. And it's a fairly prosperous town. It was about 14,000 when I was growing. It's about 20,000 now.

So it's grown, you know, and everything. But all the shopping is done at the shopping center outside the town. There's a lot of vacancy in the retail. The question is, are you noticing changes when they're happening quickly enough? I think that's really the issue here.

Jeffrey Madoff: For the business, that's absolutely the issue. Whether we're talking about Kodak or we're talking about local papers, when Craigslist basically took over the classified ads and destroyed the primary revenue stream for newspapers, local newspapers.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. But it's really interesting, you know, like Google and Facebook had the, they drove all the newspapers, you know, the death of newspapers and magazines has happened a lot because of search, because of Facebook. And they have about 70% of retail ads now, those two companies. It's like The New York Times. The New York Times used to be a lot thicker than it is today. I'll just pick one subject, that the polarization has happened because of where the advertising dollars are going. Where they used to go to newspapers, they don't go to newspapers anymore. And that the newspapers that have survived are surviving because of online subscriptions, not because of paper subscriptions. And the whole point is that the people who get The New York Times online are a smaller portion of the population than the people who used to buy it on the street.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I think that used to be a big thing, Saturdays at 9:30 in the evening. I'd be there standing next to people like Joseph Heller, who lived on that corner and all that, but New Yorkers waiting for The Sunday Times with the arts and leisure section, and it was, you know, this thick. That's gone.

Dan Sullivan: You've got weight left to it.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right, that's right. And you'd flip through to make sure the book review section was in there, the arts and leisure section was in there, the sports section was in there. But between Craigslist, which put the initial dent into it, and then, yeah, the online advertising and all of that. Now, it's interesting, The New York Times has been very savvy in terms of what they've done, and they have done well. And again, some of it, it's just, things are different.

You know, we can look back and look at, and I think it's fascinating to look at the things that have changed from the businesses that were household names that we've talked about that no longer exist to the new businesses. And then there were, there's always those things that make a huge impression when they first come out, like a Segway. That was going to be the way we walk around the city. That was going to revolutionize everything in terms of urban living. Nothing. But do you remember how big a deal that initially was?

Dan Sullivan: And then the predictions that were being made.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. And I like checking out the things that didn't make it, all the predictions. What are the predictions that, like the Segway, that actually things went nowhere? You know, there's a lot of that too. We tend to forget that. That's, I think, one of the best jobs is you can be a prognosticator and try to guess the future. And of course, it's like singularity is almost here. The almost is the point. It's not yet. But yeah, the Segway, and do you remember the Google glasses?

Dan Sullivan: I was thinking of that just as you were saying it. And first of all, you couldn't wear them in social situations, because nobody wanted to be photographed. Like bars, they found in Silicon Valley, no bar would allow someone to wear Google glasses. Which is understandable, you know. Yeah, because people don't want to be that someone's taking pictures of them for a lot of different reasons. They don't want to do it. Yeah. I think that it's very interesting. Toyota, two years ago, decided not to create electric cars.

Jeffrey Madoff: Is that totally?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, they're going totally for hybrids. They're just improving hybrid. And they say, why not have two fuels? You know, keep improving the efficiency of gasoline, keep increasing the efficiency of electricity. Okay, let's be working with both of them because, you know, the biggest problem with electricity, except for certain geographic areas, there's no charging station.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I mean, that will be taken up as a potential huge opportunity for some business, I don't know if it will ever pay off. You know, I just don't know. And I'm happy not to own a car because I can rent it.

Dan Sullivan: But Babs has a Tesla and we have a charger in the garage. If you don't have a garage, it's really hard to have it in city traffic because it's a pain, you know, the building that you work in, if you drive there, doesn't necessarily have chargers. That would be a good opportunity to charge your car and everything else. But the real problem, gasoline took off because gas stations were really profitable right from the beginning, okay? These things are not profitable.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, do you remember when we were kids, you go to the gas station, they automatically cleaned your windows, they had the squeegee, the guy wore a uniform, you know?

Dan Sullivan: City service, remember city service?

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I do.

Dan Sullivan: Remember the guys in the uniform, you know, city service always had, you know, they were very polite and they washed your window, they checked your oil.

Jeffrey Madoff: And there's none of that anymore. It's self-service at the gas station, and there's none of that anymore. Yeah, it'll be interesting to see what happens there because the charging stations and whatever the range is limited to is going to be a handicap until there's some other way, whatever.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, the real problem is no resale value. They have the zero resale value. And a lot of the gas cars, there's a real market with resale.

Jeffrey Madoff: No, but sales for electric vehicles were up I think 8.3 percent last year and it was interesting because of all the blowback that Tesla has gotten in Europe, their sales were down 49% and Europe was where it was 8.3 percent up in electric vehicles.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I mean, I think that's normal. As far as I'm concerned, it's probably a niche. First of all, they're very expensive. They haven't gotten it down to, you know, $20,000 for, I mean, the Chinese have, but they're gonna be blocked from shipping them anywhere. You know, so it's, I think the way things are going, you won't see any Chinese electric cars in the United States.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I think that, I don't know, I think it's the history of the gas station, and the protection that that gave companies, you know, in terms of the availability and so on. I mean, that's another thing that's also changed tremendously. That's changed dramatically too. But I think that when you look at all the things that have changed tremendously, there are certain things that those companies have. And one of those things is that there's not the same kind of infrastructure that takes years to build for so many kinds of businesses that they're used to, you know?

Dan Sullivan: Well, you know, businesses that really capitalize on electricity have a much bigger future, you know, because electricity is the most intense form of energy, okay? And then the question is, where are you getting the raw energy to turn it into electricity? Okay, that's really the big issue. And the other thing is I was reading this great book. It was written about 20 years ago. It's called The Bottomless Well. And he makes an interest. This is 2005. And do you know what 40 percent of the electricity in the United States is used for in 2005? 40 percent of the energy in the U.S. was making more intense forms of energy. Okay, so in other words, energy itself is used to make more energy.

For example, lasers require an extraordinary amount of energy to create a laser. And lasers are just incredibly useful. They're just incredibly useful. They're very, very expensive. I noticed Israel announced on Tuesday that they had knocked out the first incoming rocket with a laser. This is the Iron Dome, their Iron Dome system. And not rockets, these were drones. They were knocking out drones that were coming across the border. And the interesting thing is it costs about $10 to actually knock down. If they send a rocket, it's $50,000. So probably within about five years, they won't be shooting any more rockets to knock down rockets. They'll be just pinpointing them with lasers. It seems cheap when you actually use it, but just the sheer amount of investment you have to make to get a laser to do that is just extraordinary.

So we're always going for higher and higher, more intense. AI just uses up an enormous amount of energy. The Nvidia chip, you know, they're the ones who are really driving AI, the amount of energy that a Nvidia chip takes to produce it and use it is equal to three Teslas driving full-time for a whole year. It's just a chip, and they're making millions of these chips. We just need this extraordinary amount of energy that we don't have right now for AI.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, and the other thing that takes up a tremendous amount of energy, and I still can't say that I understand it, but is Bitcoin. The computational power that that needs is crazy. But it's going to grow. But I mean, that's, you know, you don't think of the computational power of just what impact is that going to have?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I've got one of my clients makes the new modular nuclear plants. You know them, they're like two trailers, if you think of two trailers.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I know exactly what you mean, yes.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and he's building four of them in Wyoming, Wyoming, and they cost a billion each. But if you have one of them, it powers 40,000 homes forever. Yeah, so let's see. No, I think that's gonna be the real breakthrough is gonna be nuclear. The nuclear energy.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I think it's well, like anything, it's like when there was an accident with a driverless car or you know what happened with, can't believe I'm blanking on the name of the nuclear center that you know, blew up.

Dan Sullivan: Three Mile Island.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, there's Three Mile Island and there was another one. Oh, Fukushima. Yeah, I think that because people are resistant to change anyhow, any reason not to change rockets to the top. It's like the sea, we told you. And one of the things, of course, that stops innovation is fear stops innovation, but also the phrase, well, that's how we've always done it. And people don't even remember why they've always done it that way. That was the only thing available at that time. But yeah, it's gonna be, there are so many things back to what you're saying about the uncertainty and how those are ultimately gonna play out, because at any given time, it seems like something's going to happen. And most of those things don't manifest.

Dan Sullivan: Or they manifest in a way that wasn't predicted.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. Yes.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, they manifest in a way. I remember all the claims about social media when it first came out. This is going to be wonderful, the amount of cooperation we get out of social media. I said, you know, I've actually never been on social media, and I've never received social media, so I'm strictly an outside observer on this. I could never see the reason why I wanted to do this. I mean, I love YouTube. I love watching things on YouTube, but that anybody can contact me anytime they want to, and somehow there's some obligation to get back to them—I get more phone calls from you than I'd have any other human being.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I'm trying to 10 extra pipeline.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, you're doing a really good job. Yeah, most of my use of the phone is for podcasts. Dean Jackson, you know, it's strictly by phone. It's not on YouTube. And I said, you know, Dean, if I look at all the use of my phone over the last year, it's mostly you on podcasts. But my sense is I do a lot of planning, so I plan things ahead. So, you know, podcasts, you plan, and yeah. I have this thing, when someone knocks on my front door, we had a case last night, it was about seven o'clock, and somebody knocks on the front door. And Babs says, who is it? And I said, they're not doing it for our reasons. They're not doing it.

Okay, first of all, there's no obligation because it's strictly for them and it was their fundraising for something. So Babs went to the door and used up about five, 10 minutes of her time because she's a generous listener. I'm not a generous listener in any way like that. But I said, just because someone gets in touch with you, it's no obligation. They're doing it for their reasons. They're not doing it for you. You know, unless you have a common project, we have a common project. But it's actually a psychological disease now. It's called connectivity, that you have to be in contact with people. You know, like if you're not in contact with people, you're being socially wrong. And I said, yeah, but is there anything to talk about? That's a big change. That's a big change.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, remember that, you just remind me of another big change. You remember, when's the last time you ever heard a busy signal on your phone? And who has separate answering machines anymore? And I'm sure that the number of people that even have landlines is tremendously diminished.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Yeah. I'll just show you something. This is the last five days. I'm just going to show you something. So we have Smith, Babs Smith, then we have likely fraud, likely spam, likely fraud, likely fraud, likely fraud, likely fraud. It's usually China calling. It's usually, and then I have Jeff, Jeff there. And I was almost, and I said, Jeff, I got to phone Jeff back, and everything else, but mostly spam and fraud.

Jeffrey Madoff: I'm happy and gratified that you don't consider me part of those two categories.

Dan Sullivan: No, no, you bypass the spam and fraud filter.

Jeffrey Madoff: So I think today we were definitely back into our anything and everything realm with a few connecting points to things that happened, massive changes that happened societally in our lifetime. Did you have any particular takeaways?

Dan Sullivan: I think the big thing, if I look back, the one thing that hasn't really changed, and that is the amount of attention you have for anything. I think human attention is very limited. It's very, very limited. But the attempts to get your attention have multiplied by a million times.

Jeffrey Madoff: It does seem like it. I mean, I think that it used to be the vast majority of things in my spam filter, but didn't come through to my email. And I've noticed in the past year, a lot more of it makes it into my email, whether it's spam filtering, which updates. and just hasn't gotten any better at it. But I get so much what we used to call junk mail when it was snail mail, you know, tremendous amount. But I also, I think it's interesting looking at businesses that were so dominant when we were younger that don't exist anymore and types of businesses and the effects that new businesses, and I'm even calling social media a new business, but the impact that has had on us culturally.

Dan Sullivan: Sure, sure. Streaming is a new business.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, yes. And, you know, AI, which has got tremendous opportunities for good and tremendous opportunities for fraud and deception. What is being done as of just the past couple weeks in terms of Gemini, Google's release of Flow, which is how you put together these AI sequences—I don't have the confidence of people's ability to discern or critically think about what's real and what isn't. And most people pass along things without vetting them because they want it to be true because it coincides with their own beliefs, whether it is or isn't. I think we all have a responsibility if we pass something on to vet that. If you're going to pass it along, vet it. Is it in fact true and how do you know that it is?

And I think that we've come a long way from the email from the Nigerian prince you know, to a very dicey area and dangerous area. And I think that people need to be more aware and more on the alert and not taking truth for granted because you like the person that sent it to you. You've got to vet information. And the way that I use AI for research, which I really enjoy it, and I can do it at any hour of the day or night, which is also a big, big plus. But anything that's important, I will vet it before I include that in any kind of claim, because it still makes mistakes. So depending on what's at stake, and for me it's always you want to be credible in terms of what you do and have that integrity because I think you can only lose that once. But it's a fascinating time because it's challenging on so many levels.

Dan Sullivan: I think human discernment actually goes up over time. I mean, I think it's behind technology, but I think it catches up. You know, I mean, I'm approaching seven years now, and I've just watched no television in seven years. And I don't have any sense that I've missed anything, you know. And I read a lot more. I bet my reading has gone up by 400 hours a year in the last seven years. And it's just, you know, I just engage better with reading, you know. So you have different filters because I've been reading since I was six years old. You have an experience of reading. Is this plausible? Does this sound, you know?

And the interesting thing, I'm not reading nonfiction very much. I'm reading mostly fiction, you know, good stories, you know, a lot of historical fiction and everything like that. And you develop a sense that this sounds very plausible, what the person is doing here. Some really great British stuff, some phenomenal writers that I've come across. But there's nine billion of us, and half of them are on social media, and so it sort of starts out after a while. I believe that the times we're living in are not unique. I think they require new responses, but that's always required new responses.

Jeffrey Madoff: I would say new responses and new responsibilities. You know, and because with a click you can pass things on. I think, as I was saying, the responsibility is to vet things before you pass them on, you know, because then you're being played.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Well, you don't like being played.

Jeffrey Madoff: No.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. So pass that on. Jeff does not like being played.

Jeffrey Madoff: Thanks for joining us today on our show, Anything and Everything. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend. For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

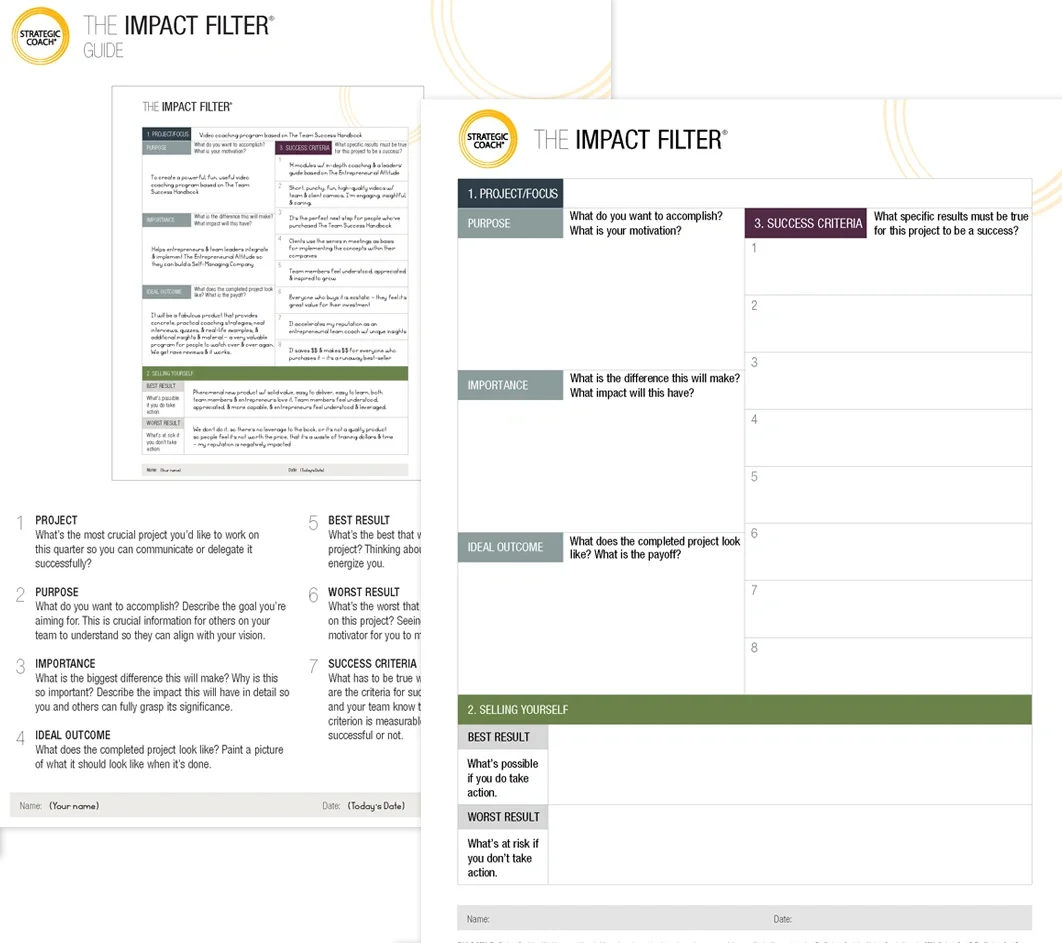

The Impact Filter®

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool