What Your Business Is Really Worth

September 02, 2025

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

Do you believe your business has an inherent value? Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff dismantle this common illusion to reveal the true nature of value. Learn why it’s determined solely by a buyer’s motivation and how building a Self-Managing Company® is your ultimate path to greater freedom, growth, and engagement.

Show Notes:

The concept of inherent value is a subjective belief, not an economic fact.

True value is determined solely by the agreement between a buyer and a seller at a specific moment.

A buyer’s perception of value is entirely dependent on their unique motivations and goals.

The ultimate purpose of your entrepreneurial journey is to achieve greater freedom of time, money, relationship, and purpose.

Selling your company often means sacrificing your freedom and becoming an employee.

Growing your business can create its own kind of prison, depending on how you build it and what you do.

Your personal engagement in the creative process is the core fuel for a fulfilling entrepreneurial life.

Money is not the game itself but merely the scoreboard tracking your progress and freedom.

Building a Self-Managing Company is the strategic vehicle that grants you the freedom to focus on what you love.

Life and business are a constant negotiation requiring you to understand the other party’s perspective above all else.

Resources:

What Is A Self-Managing Company®?

The 4 Freedoms That Motivate Successful Entrepreneurs

Casting Not Hiring by Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff

“Scary Times” Success Manual: How To Be A Leader When Times Get Tough

Never Split The Difference by Chris Voss

Freakonomics by Stephen J. Dubner and Steven Levitt

Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases by Daniel Kahneman, Paul Slovic, and Amos Tversky

The 4 C’s Formula by Dan Sullivan

Episode Transcript

Jeffrey Madoff: This is Jeffrey Madoff and welcome to our podcast called Anything and Everything with my partner, Dan Sullivan.

Dan Sullivan: Jeff, today we just mentioned something that might be of great interest and it's, I don't call it this, but it is called the pricing mechanism of the marketplace that almost anything you can think of is worth what a buyer and a seller will agree on.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, it's interesting because there is an illusion of value.

Dan Sullivan: Inherent value. It's called inherent value.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes.

Dan Sullivan: That things have inherent value. Actually, they don't. They have whatever value gets determined by an agreement between a buyer and a seller.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. I like the idea that the concept of inherent value has no value. Not unless there's a buyer and seller that agrees on it.

Dan Sullivan: That's right, that's right. It's an interesting idea because I would say among the people who feel they're knowledgeable about the world, that more people believe in the concept of inherent value than in the pricing mechanism of the marketplace.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think that's right. I think that's right. And this spills into a lot of areas. We were talking about my dad, who was approached to buy a property, this was back in Akron, Ohio.

Dan Sullivan: What era was this?

Jeffrey Madoff: This was in the early 60s. My dad had some interest in the property, and he made the guy an offer, and the guy said to my dad, well, it's worth much more than that. And my dad said, to who? And then there was silence. And my dad said, this is my offer. And I says, well, I'm not gonna sell it for that. He said, okay. About seven months later, he calls back. My dad, he says, Ralph, you know, I'll accept your offer. And my dad said, well, that's not my offer anymore.

And he said, well, you were willing to pay that before. And he said, well, I'm not willing to pay it now. It's seven months later, and you've now established that the market doesn't agree with what you think it's worth. So I'm not interested. I'll do it at this price, but not that price. And my dad ended up not buying it because he didn't think it was worth it. And my parents, mom and dad, were in retail. And you bought something wholesale, you sold it retail, there was a profit margin in there. If you couldn't sell it for that retail price, eventually it goes on the sale, then it goes on the clearance. And sometimes you donate it to charity because you can't sell it.

You can't really say that anything has a value that holds forever. And that it gets as simple as there's a buyer, there's a seller, and those are the only two people that have to agree on a value at that time. So I think there's also, it feeds into a certain illusion, even when it gets into a nation's economy, a global economy. You know, who's buying what for what, what affects prices? And I always questioned, and I'm curious about your take on this, Dan, I always questioned the illusion of value. Because if nobody's willing to pay what you're asking, you can ask whatever you want. That doesn't mean it's worth that. And we were talking a bit earlier about inherent value. Go into that concept a bit if you would.

Dan Sullivan: Well, inherent value means that there's a value that's determined or someone believes that something has a value. It's very much like the person your father was dealing with is that he was building in all sorts of reasons why he thought his property was worth more than your father was offering and what the marketplace was telling him so far. That there's a value, you know, and it could be a lot of psychological and emotional factors that he's building into what he thinks the value is. It could be how much he's invested in the property already and he wants to get his investment back. It could be anything. The person's thinking is not within the framework that this is worth what somebody will pay me for it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. I mean, you know, it's not a fact. You know, it may be a desire. It's a belief. It's a belief and it's a highly subjective belief because, I mean, look, currently, wasn't that long ago, Teslas were sought after. The value was high. The stock was doing very well.

Dan Sullivan: And then Elon created a few new strategic messages in the marketplace that changed the value.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes, yeah. And so, you know, there's nothing inherent that is going to maintain the value of something. You know, with my students, I would hold up, this isn't a bottle of that, but I would hold up a plastic bottle of water. and I would take it from a student. I'd say, can I take your bottle here? And I'd hold him and say, how much does this worth? How much do you pay for this? He says, it was a dollar and a quarter at the convenience store. And I said, okay, what if I told you it was $100? And the lad said, well, I wouldn't buy it. I said, why? He says, it's not worth $100. I said, okay, all right.

Now let me change the given circumstances here. We're in the desert. That's all the water that there is. And I have it, and I'm a prick. And I'm willing to sell it to you. For $100. For $500 now, because it's the only water that's around. Yeah, is it worth it? What about $1,000 if it's between life and death? Is it worth it? The value changes dynamically based on demand, need, and other factors of the marketplace. So to your point, I don't think anything has inherent value. I think that that value is very much given circumstances, to use our theatrical parlance, what is the context that we're talking about? And if the context is the desert, it's very different than, well, the hell with you. I'm just gonna go to the convenience store and buy it for a buck and a quarter. Well, if you don't have that option, the circumstances change, the value changes.

And if you talk to any realtor, what you were talking about is, you know, there's all kinds of different effects, but it can be also personal, what you think something is worth, because maybe it's that house that you've lived in and raised your kids in. It has all this emotional value for you, which means nothing to the potential buyer, but they think their house is worth a lot more. And I've talked to many realtors because I found that really fascinating, the perception of value, which the way to test it is see if you can sell it for what you think it's worth.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, it's really interesting. We have a member of our Strategic Coach Program, his name is Pete Worrell, and he's from Portsmouth in New Hampshire. And he's got a company that helps entrepreneurs sell their companies to other people. And he's got a whole process. And he makes a judgment about whether he wants to take on this project or not, you know, and he'll look at all sorts of things. But one of the things you have to agree that it's going to be about two years before there can be a sale, okay, before there's a transaction. And then he does an analysis of the company of everything that would constitute friction in a potential buyer's mind.

In other words, and one of the big ones, and Jeff, you probably know this, it's desirable if your company doesn't have any relatives on payroll. Because someone who doesn't want, when they buy your company, they don't want to buy your family. So they don't want to have an argument with it. And there's many other factors. And then they'll get the books cleaned up so that they're straight books. They'll upgrade the physical aspects of the business. They'll show profitability and everything like that.

So there's a whole series of things that it takes about two years to turn things around. And then he goes to the marketplace and he's looking for at least 10, maybe up to 20 offers from the marketplace, and he said that the difference between the low bid and the high bid is about 60%. In other words, the high bid is about 60% higher. And then he's got a diagram, and he shows where all the potential buyers are, and then he'll pick the three who are bidding the most, and he'll interview them, and he'll say, now, I want you to answer a question for me, and said, what do you plan to do with this company once you own it? And what happens is that there's a competition then that sets up between the three top buyers already, and they push the price out another 60%.

And he says, the one who sees this not as an end, but they see it as a means—in other words, we need this company. This company is crucial to the growth of our other companies, and we need this. And he gets them bidding. And so in the final analysis, he'll get like 100%, 200% higher for the sale of the company. And this is all, you use the word subjective, this is all subjective, okay? And a lot of people don't realize this, but all sales are subjective. In other words, the buyer has something in their mind for something that's not detectable from the outside.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, yeah, I mean, there's a number of examples of that. I was actually, I got an email Thursday, you know, I have a Fitbit and it said that Fitbit will stay supported until you have to change your account to Google by February of 26. I didn't know that Google had acquired Fitbit. Fitbit, you know, is a major player in that market. And I've seen this happen many times. My guess is that in just a few years, not many, after it's bought, it just becomes another Google product with the Google Watch and their phone and all of that, because it's got its own ecosystem and Fitbit will be a name in history.

And there are so many times that companies I had, I'm unfortunately blanking on his name, but the guy that founded Dodgeball, which was one of the first geosocial networking sites, it was bought by Google in the early 2000s. And he thought, oh, this is great. I'm going to get the capital I need to really build this company into something. And in fact, what happened is in two years, Google shut it down. And the reason they shut it down was it was competing with products that they wanted and saw it as a threat. So they had the money to buy it and kill it.

Same thing happened with there is a Meerkat and Periscope, which were going to change the way we view the world, and it was a camera in your phone that you could then stream live to someplace else, have it recorded, so all of a sudden, events could be shared, all kinds of things like that, and that was bought by Twitter, which they then shut down. Then their own technology, which was far inferior to the other, went out of business, and then they're out of that whole business. I never realized before, I mean I've realized it for maybe 30 years. Now I'm old enough, I was still an adult 30 years ago, but buying companies to close them down because they pose a threat.

Dan Sullivan: There was a book called, it was about a man who worked for Facebook and he was involved in Facebook just when they were working out their advertising model. Okay. And they created competitive teams in terms of Facebook. But part of what they had to do is that they had to start buying out some other companies to get the right pieces in place for the advertising model. And they went ahead with the purchases. And the person who's writing the book, something monkeys is in the title. I forget the title. It was a really good book. Rodriguez is the name of the author, I think. And he said a lot of people don't realize that when someone buys another company, they're actually not buying the thing that the company has created. They're buying the team that created it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I have interviewed so many private equity people over the years and people that invest in things. And I have some good friends that are in private equity. And one of them had done very well early on. He actually went through an interesting business that failed, although it got phenomenal publicity. And he was amazed by the amount of press that they got in the financial papers and all of that. It was a company that, his name is Daniel Gulati, and Daniel's a dear friend, a very smart guy. And he said it was such a schizophrenic experience, because we're getting all this publicity, big publicity, and we can't even make payroll. He said it was really rough.

And at some point, the story of this business is gonna be told, because it's such a fascinating story, but probably not as unique as I initially thought it was, where these companies that have a high public profile but are financially very vulnerable and distressed … and when I've talked to my friends in private equity, and I said, what do you guys look at first? I said, well, we want it to be within a particular sector. We specialize in consumer electronics or we specialize in medical devices or, you know, whatever we want it. Many of them specialize in a certain area of expertise that they feel they've mastered somewhat. And I said, so how important is the idea compared to the team that executes that idea? And they said, no, the team's everything.

Because if you can't execute on the idea, he said, but you have to understand what private equity, why they invest in a company, there's one reason. They said, what's that? And he said, to make money. And I said, and so what does that mean? And he said, well, what that means is there's usually a five-year window and you're not profitable they'll shut you down. Different than a company that might buy a vendor that either has complimentary products and they wanna be able to dominate a market or get a bigger foothold in the market. But when you're dealing with private equity, they're killers.

And it's interesting because the inherent, the nature of the value changes. Because they're only about, you know, it's like somebody who steals a car and strips it of what's valuable and resells it for as much as possible. And then there's just that car body that's sort of empty and abandoned. And that happens more often than it doesn't happen with companies that get acquired. So I think it's really fascinating because it's also, why would somebody buy a company? Do they buy it to make money? Do they buy it to secure their position in the marketplace, which they hope will lead to more money? But I think that it's … or they buy it for a tax write-off. It could be that too.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. I think what's really coming across from all your examples, Jeff, is the fact is, unless you would know exactly what the principal motivation is that the person who wants to buy it, unless you're real clear about that, you have no basis of getting what you would want as value for what you're selling.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right, and that is hand in glove with the concept in theater of Stanislavski, the given circumstances. What are they looking for? You know, because if I talk about how great my product is and how superior it is to everything out there and everything else, and we just need the money to meet this, they don't care.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and their not caring should not be interpreted as some sort of moral judgment about them. They have a purpose, that's their purpose. And they're looking for capabilities that will help them get to their purpose. Okay. It just happens to be that what you're offering to them doesn't fulfill their notion of a capability.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. And I think that a lot of people misinterpret that mating dance, if you will, because the company who's putting in the money may be looking for one thing. You may be thinking, oh, this is my savior. Now I'll have the money to grow this business the way I want. No, you'll have the money to grow the business the way they want, not the way you want. And that's, I think it's also, it's something you and I were talking about before, which is, you know, I've been talking to different companies and reading about like Wegmans, the grocery chain, Trader Joe's, which is another grocery chain in the same category. And there are companies that Kohler, another one, the innovative plumbing company, or whatever you would call it, with the accessories for bathrooms and sinks and all of that.

Anyhow, these companies, all multi-billion-dollar companies, what they all share is that they're privately owned. So everything they do is to enhance their value to their consumers in building a certain brand loyalty, which those have done. which is, you know, now those happen to be business to consumer models, but their interest in why they never went public is because they didn't have to. They grew through their own revenues and weren't in the position where they were really vulnerable. And I think that a lot of people look at when they complete their round of funding, to me, what you've done is taken on more debt. You know, because until you can walk away from that, it's debt.

Dan Sullivan: It's your money.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right, that's right. So you deal with entrepreneurs, that's your entire client base. All private. And so how do you respond to what I'm saying in terms of I think that the value of a company and the values and what they base their decisions are on is very different between companies that are privately owned and those that have gone public? How do you see that?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, first of all, I mean, I started small. I was a small entrepreneur and I started with small entrepreneurial clients who were all private. The other thing is they're 95% service companies. They're not manufacturing, they're not necessarily retail. That number is growing, the not services as we go forward, where the product can be an idea, where the product can be digital, you know, so it's not that you have an inventory that you're selling.

But very interesting, what I would say, the question that we ask of all of our clients, and we do it in the very first day that they spend with us in a workshop, is what do you want your personal life to look like five years, 10 years down the road? And what I mean is how much freedom do you want to have from your company as you go along while still owning your company? Okay, because the whole thing has to do with who the team is that they put together and how the team interacts with the marketplace.

Okay, so our whole emphasis is what we call a Self-Managing Company, that the owner gradually can be in a position where they have lots of their time transforms within a three-year period, where what they're doing when they're actually working in the company is what they love doing, okay. So it's, you know, the part of the business that they actually love doing and for the most part it's not management. We have very few people who is desire is to be in management; their desire is in to be leadership. Actually growing the company, creating new opportunities, creating new markets, creating new … they love doing that.

So that's what they want to do while they're working, but what do you want to do when you're not working? And this is a new area for a lot of them because they've been entrepreneurs since they were 10 years old out in the marketplace selling something. And it was always about work, work, work, work, work. Even when they're supposedly on a weekend day that should be free or a vacation day that should be free, they're working. And so right off the bat, it's a decision.

And the one thing that's incompatible with their desire for freedom of time is going public. The moment they go public, they have no control of their time. Somebody else controls their time. Okay. So our entrepreneurs are unique in the sense that they're looking for greater and greater freedom of business time and personal time as they go along. And they don't want to be reporting to someone, you know.

Jeffrey Madoff: So you have built up, you know, a substantial company that allows you and Babs to live well and have the freedoms that you are after. If somebody approached you, has anybody ever approached you to buy Coach?

Dan Sullivan: Yes.

Jeffrey Madoff: And how do you respond to that?

Dan Sullivan: I said, if I sold it, what would I do then? And they said, well, you know, you can, you know, and they have no answer because they have no idea of what I'm really after in life.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Yeah. I mean, the whole thing is that whatever stage of growth we're at, that what lies in the future is bigger, you know, from our standpoint. We're 36 years now, and our business model is exactly the same as it was in 1989. We're offering a way of thinking for entrepreneurs that re-engineers their company in such a way that they have greater freedom of time, money, relationship, and purpose. And that's what they're after. They're after freedom.

And I said, if you sold your company, would you then retire? And they said, I don't want to retire. And I said, well, that's probably a good reason not to sell your company, that you don't want to retire. Because when you become an employee of the company that buys you, you'll want to retire really fast. And I said, the day after someone buys you, they're the majority owner now, or the total owner now, and you come to their premises, which used to be your premises. They don't like you, and you don't like them. You know, so the ownership, you know, it's, I think that owning your own company is a great vehicle for personal freedom in the world. If you have the skills to do that, and if you have the, and if you get rewarded by having this vehicle called your company.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, that raises another question to me, is that there is always the push for growth and pushing sales higher, all of that all the time. I would say that, and I don't know what, I don't think many people ask themselves this question. I would ask about, what is important to you? Outside of your work, what is important to you? Some people, their work is their total existence. And whether Coach does X, let's say that you're at X amount of business right now. This doesn't have to be Coach, but let's personalize this and put it on Coach. Your business is X, and if you did certain things and got marketed more, live event, whatever it is, and you could, I'll use your term, 10x your business.

How much would that impact your and Bab's life? And would you be willing to do those things, because that growth doesn't come without work and commitment and all of that sort of thing. Or are you at a place that, you know, we've steadily grown, very happy with where we're at, everything else is a bonus, but it's not like I need more money. And my satisfaction comes from other things or the things that I do within that and 10x-ing my business doesn't really change my life in a material way that I'm looking to change it.

In other words, it's a long way of saying, do you think that it is always the goal that you have to grow your business? Or can you be happy with a smaller business that affords you the opportunities you want and the likelihood of you having to compromise those values and things that you want don't come into conflict?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, I think the do we want to grow or not is really the crucial question. And I would say that if you don't want to grow, you aren't going to keep the team that you have that's gotten you to this level of growth. And you're not going to attract new team members who are growth-oriented team members. The other thing is that it'll affect the type of clientele you have, that probably the only way this has happened would be that they don't want to grow. And you can see that. I mean, professionals kind of work on this model. Dentists reach a certain point and all they want is their present level of dental. It's a built in, people have to get their teeth checked on a frequent basis.

Doctors, lawyers can do this, accountants. But I think if you're in a marketplace where the marketplace is changing and even to stay where you are, you have to change. All the professionals are going through a profound crisis right now because of automation and because of regulation. They're going through a profound crisis right now. But my case is I love the activity of creating new thinking tools for entrepreneurs. And I can't see a point in the future where I won't feel that way. And our thinking tools, we've discovered, have intellectual property value and they're assessed through patents.

The other thing is that I really enjoy coaching people who are now 40 years younger than I am, 50 years younger than I am. And it's really interesting to see, is there a difference to younger generations and the entrepreneurs? And what we've discovered is that the common factor for someone who's 70 years old over, but I have the youngest we have right now is 21. So I'm 81 and they're 21. So it's 60 years difference. They want freedom, and I'm for anybody who wants freedom. I'll help anyone to get freed up. So I think, you know, I don't see any threat in the marketplace.

We've gone through all sorts of different technological jumps over the last 36 years. We've seen all sorts of coaching companies come into the marketplace and not last very long. And so I think we've got a good thing going. We have, you know, if anything happened to Babs or me, all the legal work is in place, all the financial structure is in place that our team could take over the company.

Jeffrey Madoff: So, yeah. Well, I guess in business, there's always the emphasis on growth. And I take your point. It's a point well taken that you may not attract a certain level of person if you've achieved stasis and you're not really interested in growing or you're interested in growing, but you're not interested in growing in a way that increases your involvement in the business in a way that you don't want to be. Because that's a different kind of freedom, right? It's not just what's imposed from the outside, it's also how you approach what you do.

Dan Sullivan: And well, if I take our first year, which was 1990, we started in November of ‘89. If I take our first year as a model, we've grown 280 times, which is great. And each stage, as we jumped along that way, I got more freed up inside the company because you had the ability to bring on other people who could handle things or do things that you didn't want to do.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right.

Dan Sullivan: Or that I wasn't good at. I just wasn't good at.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. I remember when, when Morgan and I first moved in together and we're getting an apartment together and she, and now she's from a family of seven kids. And I know what that's like. And so she said, you know, there's chores to do. Why don't we clean the windows? I looked at her like, what? I said, this isn't the Lassie program. I don't do chores. I work so that I can afford to hire people to do all this stuff I don't wanna do. That's part of the reason I work. And one of those things I don't wanna do is wash windows.

And it was kind of a funny moment because to me, it was freedom from doing things that I didn't want to do. And I guess the flip side is, yes, you also have freedom to grow your business, But I think one has to realize that growing your business can also create its own kind of prison, depending on how you build it and what you do. Because I think a lot of entrepreneurs don't believe that anybody is good enough to delegate, and they trap themselves because they don't know how to delegate those efforts, which is also going to impair growth.

Dan Sullivan: That's one of the number one reasons why a small company is a small company.

Jeffrey Madoff: Mm-hmm. Yeah. No trust.

Dan Sullivan: Well, it's a certain kind of arrogance, but I think there's a fearful side of arrogance, and that is that you just don't trust other people.

Jeffrey Madoff: Mm-hmm. Yeah. Which I think comes from early in life. Yeah. Whatever happened that promoted that or caused that to not grow or whatever. Mm-hmm. Always important to be vigilant and have your eyes open. But trust is an interesting thing.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. The central theme of our podcast today is the value of things and about hiring people, you know, or casting as we're writing the book on casting. And this is where casting is really different from hiring now that we're on this topic, because when hiring, you're thinking in terms of tasks. There's this task, there's this task, and there's a bundle of tasks, and we'll call the bundle of tasks, we'll call that a job, okay? I think some of the thinking that goes along with that is that we have to have somebody to do that, and we don't want to do that, and so we bring in someone who will do this. Whether they like it or not is not really part of the question. They applied for the job, so there you are.

Casting is very, very different. Hiring sort of is past-oriented. This is what we've needed up until now. Casting is, if we think about where we are, let's use three years. So we're doing this in 2025, so we're talking about 2028. We want a capability that somebody comes in and creates a whole new leadership position, and they take care of everything that's going to allow us to get three years out. I think that's a very, very different proposition. And the biggest reason why I think what happens with entrepreneurs, why they don't grow is they had a certain level they wanted to get to in terms of income, in terms of lifestyle, in terms of maybe status in a particular industry, and they get there. They get there.

And that's it. They flatline. They flatline. Like, now it becomes a question of either selling, or it becomes a question of just holding where we are, and then doing as little work where we are so I can do other things that I want to do. And I used to be confused by this because until they got to the status and to the position they wanted to, they did do things to get there. But once they got there, they weren't interested anymore. And the entrepreneurs I'm really interested in is there's no upper end that they're getting to. There's just the next growth stage that they're getting to.

So that's the way I do this. But more and more, you're looking for people who will take ownership of the whole section of the future and develop it and create structure around it and create, that's what I'm really looking for.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, what you said earlier today, which is, I think, a really important and telling aspect, when I asked you about Coach, in retirement or selling the business, you talked about, well, I love building these tools. So just like I love doing the writing and the play and that sort of thing. I put that under the umbrella of engagement. The necessary condition for me is to be engaged in what it is I'm doing. If I'm not engaged, it's torturous to me. I just don't want to do it. I don't want to do it.

And so I've always looked to recognize an opportunity to be engaged. And I think that's a really important thing because as long as you're engaged wherever the growth takes you or whatever, I think psychologically such an important aspect because you're doing something you want to do. And to me, that's really the freedom to say no and not have catastrophic circumstances as a result.

Dan Sullivan: And the freedom to engage with what I want to do is … I think you just identified, you know, if there's a center of the entrepreneurial universe, I think you just put your finger on it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Which is the engagement?

Dan Sullivan: Engagement, the engagement.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I mean, and the thing is, I mean, our book project was a spontaneous discovery that, you know, when I mentioned the casting not hiring and you immediately stopped our conversation, whoa, wait a minute, there's a book here. You recognize that. And the prospect of doing that was very engaging to me. Now, there's been many other things that people said, oh, I'd really like you to do this, or no, I'm really not taking on anything now. And that engagement, I think, for me, is what's most critical. Because that's the real fuel that you're excited about what you're doing.

And I think that there's far too little self-examination that goes on and people try to blame certain things for why things have solved for them as opposed to just like, you figured out starting a business, you gotta figure out these things and that requires some asking questions that aren't always comfortable to answer. Like why are you doing this in the first place? And I think about also, I know the impact COVID had on my company because all live production stopped with you. If there wasn't Zoom, what would happen to Coach during that time? So, you know, in the resourcefulness it took to adapt and adapt quickly, going through it, it's a rough thing, but it's also fascinating. Because when things are really at stake, that's when they get interesting.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I mean, we had been through not as serious a situation as COVID, but we had had, you know, you have downturns. The big downturn in ‘07, ‘08, ‘09, the subprime, that was a big one. 9/11. 9/11 didn't really affect us that much. That really wasn't a big one, but we had a previous COVID-related, it was called SARS. I don't know if you remember the SARS. But the place where it hit worse in North America was Toronto, one hospital in Toronto. And the word went out through all the American media, don't go to Canada, don't go to Canada. Well, you know, we had an awful lot of Americans coming to Toronto and to Calgary and to Vancouver. And that's where our main centers were. And yeah, it was a hit.

But that sort of thing can happen. So we had been tested before we had been tested. And we had all sorts of rules in place of what happens when something like this happens. So when COVID started, we just noticed we were getting half workshops. And people were phoning and saying, we don't know if we can come and everything. And our team, our rapid response team, if you call them, were on. And they said, okay, we have to break the glass box, pull out the manual. Read the manual and I would say we made a decision on the 13th of March in 2020 and by the following Friday, it was Friday the 13th when it happened, and by the 20th we had a complete new game plan and we were in operation with a new game plan.

And we already knew how to use Zoom because we were a three-country company, so all of our back stage were doing a lot of Zoom work. It was just that nobody was at the other end. What changed wasn't our use of Zoom, it was other people's use of Zoom. Yeah, the acceptance of it and starting to use it. So that was it. But we were used to the, and I actually like those type of situations.

Jeffrey Madoff: Because?

Dan Sullivan: Well, it just really tests really clearly what's real about your company.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I mean, I feel on a certain level in my production business, you know, the old saying, you're as good as your last job. So whatever I did that did well, I had to somehow build and exceed in that. With the play, each time we have mounted a production, you know, that's another climb, another stretch, another crossroads, you know, all of those kinds of things come into play. And I guess at this point, I look at it all as not just part of the roller coaster that is life.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, you mentioned that Chris Voss, the person who wrote the book Never Split The Difference. And, you know, he's brought skills from hostage negotiation into the marketplace. And he's created a really great company called Black Swan. And we just had our whole team the week before last go through his training of negotiation. And I, I was in the class, I was pretty familiar with all the concepts and everything that Chris teaches, and somebody said, you know, this is really complicated. And I says, no, there's a way of looking at life that makes everything simple. And I says, what it is, you're born, life is simple, that's one sentence, you're born, that's another sentence, the third sentence, then the negotiation begins. Life is a negotiation. And the biggest skill of negotiation is being in the other person's head and knowing how they're looking at things.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. And, you know, without knowing that, without knowing what their agenda is, because, you know, I know my agenda walking into a meeting for something, you know, whether I'm trying to get someone to invest in the play or whether it's whatever it is, you know, pitching a production, whatever. I know what I want to get out of it. But I got to be aware of, as our friend Joe Polish said, you know, what's in it for them. And I think that's a very important preparation one can do before entering into any kind of a situation, you know. And too many people are just consumed with wanting to just get their words out and not listening and asking questions.

Dan Sullivan: Or get their way.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. So I think that, you know, we started off talking about value and growth and public and private businesses and engagement and so on. In the hierarchy of things in business, what would you say is your top priority? Is it to make money? Is it to, and you know, there's no wrong answers here. This is all subjective. What would you say it is?

Dan Sullivan: Well, money is not the game for us. Money is the scoreboard on what kind of progress we're making. You don't play a game by looking at the scoreboard. You do it at the end of the first quarter, using sports term. The big thing for us is that, and I think it would be true for both Babs and I, that we're very, very stimulated by the quality of the team that we've grown over the years. And we're very, very excited about the ambition of the entrepreneurs that are coming into the Program. And we're very, very excited about the new stuff that we're creating that keeps people in the Program and keeps people in the company. And so it's a constant growth cycle. And neither of us has ever talked about retirement, neither Babs or me. She's in her seventies, I'm in my eighties. And what lies ahead is more exciting than what we've already done.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, when you mentioned that you don't play the game by looking at the scoreboard, it made me think of, you know, there's a concept and we both heard it when we've listened to baseball games, you know, or watch baseball games, and it's the notion of the clutch hitter, and how Roy's a great clutch hitter with Ben on second and third. With all that, there is no such thing as a clutch hitter. The data is that your batting goes in waves and sometimes you get hits when people are on base, sometimes you're out when people are on base. There is no data in any way that proves that there is a clutch hitter. It's just sometimes you get hits and sometimes you don't. It's like looking at the scoreboard, yeah, we know we need three runs, what are we gonna do? You always wanna stay ahead and get the runs.

So you're right, the game is not on the scoreboard. That's showing you a result at that moment in time. And the idea of that clutch hitter or those clutch decisions isn't real either. In life, I think there are so many shared illusions. And there is also, and this is a psychological term, there's an illusion of evidence. You think that this is evidence for what you're saying, when in fact, it isn't. There's nothing that backs that up, but it's become an opinion that was calcified somehow into fact. Perceived fact, it's not really fact.

Dan Sullivan: It's really interesting. This is being talked about right now, the topic that you're, there's a sports phenomenon happening right now, and it's the National Basketball Association, they're down to the final two teams now, and the media would love that every year the National Basketball Association Championship is between Boston, a great historic team, and Los Angeles, a great historic team. And there's such a myth about these two powerhouses for the last 50 years, but it's a bit disappointing this year because it's Indianapolis versus Oklahoma City and now to the two powerhouse metropolises in the United States.

But there's one player on Indianapolis in the most crucial game in the first three series has hit the last shot with one second left on the scoreboard and won the game where they were the underdogs. So three times he's done it and they just started the new series. They're vast underdogs and they were down by 15, they came back and he won the game. So four times in a row he's done that. History will call him a clutch player. So what I'm saying is, clutch is a historical interpretation, it's not a future interpretation.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, that's right. And the notion of that creates a certain mythology, you know, which wasn't really true. Now, probably, to use your example, get the ball to him in the last couple seconds to take the shot. So he has more opportunities than maybe he had before they deigned him a clutch player. You know, it's kind of interesting because those kinds of things tend to take on a life of their own. And it becomes, you know, just like the notion that the celebrity deaths come in twos or threes, whatever it is.

I mean, that's not really true because it ignores what happens the vast majority of the time is this person died. It wasn't anybody else that died that day that was that famous. But it becomes these kinds of myths that we buy into. And I think that it takes us back to the economics we're talking about is the myth of value. And it's not a myth, it's a true value comes from an agreement between at least two parties. There is value there.

Dan Sullivan: But let's go back to one of the stories that you were using for proof of the power of casting over hiring, and that's Billy Bean of the Oakland Athletics. He was doing, from my reading of what I knew and what you've told me, is that he's doing a reader under these circumstances, this person will perform better than other people.

Jeffrey Madoff: Not quite, really. What he did was looked at, the primary question he asked was, how do you win ballgames? And you win ballgames by getting people on base, because then they're in the position to score. So, and I love this example. So he looked at what was considered kind of a neutral event, which was a walk. And if you got a walk, you got on base. So he did look for people who had a record of being walked a lot, because that not only got somebody on base, you forced the opposing pitcher to throw more pitches. So fatigue physically and then the mental frustration that the person's getting on base and they reverse the count and they ended up taking the four balls and getting on the first and moving everybody along.

So he wasn't looking for a particular skill as much as looking at, here's the result, and how do we get that? Like the pitcher who we talked about, who his father had had a stroke, so the guy's form was so weird, even though he was a very effective pitcher, none of the scouts thought that he looked like a real baseball player. And then, you know, Bean drafted him, and he was terrific. So it was looking at the circumstances, and then really drilling down into, okay, forget the mythologies. How do you actually get people on base?

Dan Sullivan: Well, I think there's a different question. How do people who get on base a lot do it? It's very clearly that some people have a better ability to get a walk than other players.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. That's a clutch walker. Well, there, you know, it's called controlling the batter's box.

Dan Sullivan: But if you had to choose five players, you had to offer, who are we going to put up there to get on base? You're going to pick one of them based on some sense that they're better at it than others. Better at getting on base. Because before Billy Bean discovered the secret, there were a lot of players who already knew the secret.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, Billy Bean, what he looked at was all this guy who worked at Green Giant Cannery was just obsessive about the statistics that, you know, how he mapped out these things and discovered these particular patterns, which was absolutely fascinating. And I just love the fact of looking at something radically different and seeing as a different pattern emerged. And that coincided to our listeners. Moneyball is a fantastic book, really, really interesting. And if you want to read two other books that'll just give you a really interesting insight into how decisions are made, Freakonomics is another one, and Heuristics and Biases by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, which is how we make decisions, usually badly, but how do we make decisions.

And that whole area there was actually created by Kahneman and Tversky, which is called behavioral economics, which is how we decide on things, which is really, really interesting, too, which we'll be having some of that in our book, by the way, Casting Not Hiring. But I find all of that stuff really interesting. I mean, I would rely on as if I know, because I don't even watch baseball anymore. I used to. You know, it makes sense to me that the guy who knows how to draw a walk against a particular kind of pitcher would be the way to go to try to get that person on base in an important situation. You know, who can I put up there at that time?

There was a really fascinating part of it. We never spoke about this part, but I loved it. This obsessive character who kept all these stats, which being bought, he did these drawings of the perimeters of where like the outfielders and the shortstop and so on would make plays. So if you had a high error rate, that would be a disqualifier for most people scouting players. What he recognized is that the people that had the lowest error rate had the smallest perimeter in which they would try to make a play because they didn't wanna screw up their low error rate. And the people who had a much higher error rate is because they often made extraordinary efforts to get at a ball and make a play, which they often did.

But the consequence of that was they had a higher error rate. Well, they were immediately discounted. And Bean saw, no, actually, they make more extraordinary efforts to go after the ball. So, of course, they're going to make more errors. They're also going to save us more games and more runs. And then I looked at a doctor situation. And it was really interesting because what I saw, I won't go into the whole story, but it was with my daughter. And, you know, my daughter has Crohn's disease and there is no cure for it. There's maintenance. Unfortunately, that's worked well.

The doctor that we first went to who was very high profile at a certain point did not want to take the case anymore. Now, part of it was he and I didn't get along because I asked questions and how dare you ask questions of a doctor. And I talked to another doctor, great man about this. I told him that story and he said, it's like in baseball. There are doctors, there are lawyers that they're not going to make any extraordinary efforts because then they can claim to have a very high cure rate. And that's part of the reason for that. That's part of the reason why you didn't like them, that they only, so anything that could possibly affect

Dan Sullivan: Oh, padding your batting average in baseball.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right, that's right, by not taking on the difficult tasks. And so I think that's really interesting. You know, you want those noble failures, those things that you go after that you don't know what the outcome is gonna be. It's like what you've talked about in terms of courage can turn into a capability and it becomes confidence.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. That's the way it always happens.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, which I think is fascinating.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Well, it starts with a commitment that will enable you to be courageous before you have the capability.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right. No, I love that. I love that. And the thing is, I start seeing patterns outside of whatever particular world I'm focused on. Then you start seeing that in a lot of places because, you know, one of the phrases that I always hated hearing from the time I was a kid in school in art class, and I'm sure you hated it too, was, I'd say, well, why do we have to do it this way? And so, well, that's the way we've always done it. Like, yes, so? That didn't answer my question. You know, that's not a really good answer. And yeah, I think that the courage, the commitment, the courage, the capability, the confidence.

Dan Sullivan: And you rinse, you … you're on to the next level, you know. And I think that's the thing that I most look for in team members. I look for them in clients that I like to engage with. And that is, do they have a stopping point in the future? They're going to get to a certain point and then they're going to stop. And the opposite of that are people who just never stop. I'll make 10 times more investment in them than the people who have a stopping point. I'm not really interested in people's stopping point.

Jeffrey Madoff: So I think we got into a few different things today. What did you get from today?

Dan Sullivan: Well, I think the big thing is that, one, going back to another idea that we've had previously, that in any situation, you're guessing and betting with the hope of a payoff. And all transactions in the marketplace, sales situations where there's a seller and a buyer, both are guessing and both are betting and both are looking for a payoff, you know, of one kind or another. And my sense is that the people who are best at this are the people who spend most of their time comprehending what the other person is looking for. And making a decision right off the bat of whether that's possible or not.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. It also makes me think about mythologies that we believe in like that aren't true. You know, because I think that the bane of any creativity or innovation is we do it this way because that's how we've always done it. And assembling the right people and pieces of that puzzle to keep a business creative, innovative, and vital is, as a leader in the business, having an idea of the ensemble you want to put together and not having that made up of people who only agree with you. Because I think the great ideas can also come from, and I underline that it's always about respect, it's about listening, and also understanding, as you were just saying, what the other people want out of it. But I think that all of these things become not just business lessons, I think they're life lessons.

Dan Sullivan: Yep, yep.

Jeffrey Madoff: And it's all negotiation. It's all negotiation. All right. So I think we stuck within the perimeter of anything and everything.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. You know, we can always expand the everything.

Jeffrey Madoff: With anything, that's right.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, with anything. Yeah, I don't have any problem with bringing in something new into the conversation. But I think there is, in the 4x4 tool, the first quadrant of the 4x4 tool that is the method in our book, Casting Not Hiring, it's alert, curious, responsive, and resourceful. Okay, and my sense is it means that you're present to what's going on at the time. You're fully engaged with what's going on and you're alert to anything new, you're curious about something that's happening that's different, you can respond to it, and you're resourceful using what you already know to respond to a new kind of situation.

Jeffrey Madoff: Absolutely, and I would say also that you know who to talk to, who will ask you hard questions and help you gain that kind of knowledge or insight that's needed, as opposed to people who will just tell you what you want to hear. I think that's important. And not being threatened by that. So much of that just has to do with how that's delivered. But as always, this has been a fun exploration, Dan Sullivan, and me, Jeff Madoff. Thank you for listening. Tell all of your friends, family, and anybody you ever meet, as you're driving down the street, roll down your windows. No, nobody rolls down windows anymore. What am I talking about?

Dan Sullivan: And shout.

Jeffrey Madoff: Shout, yes, shout. Shout what you're doing there. That's right. And tell them about Anything and Everything.

Dan Sullivan: And if they don't pay attention, go around the block and tell them again.

Jeffrey Madoff: That’s right. Thank you all. Thanks for joining us today on our show, Anything and Everything. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend. For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

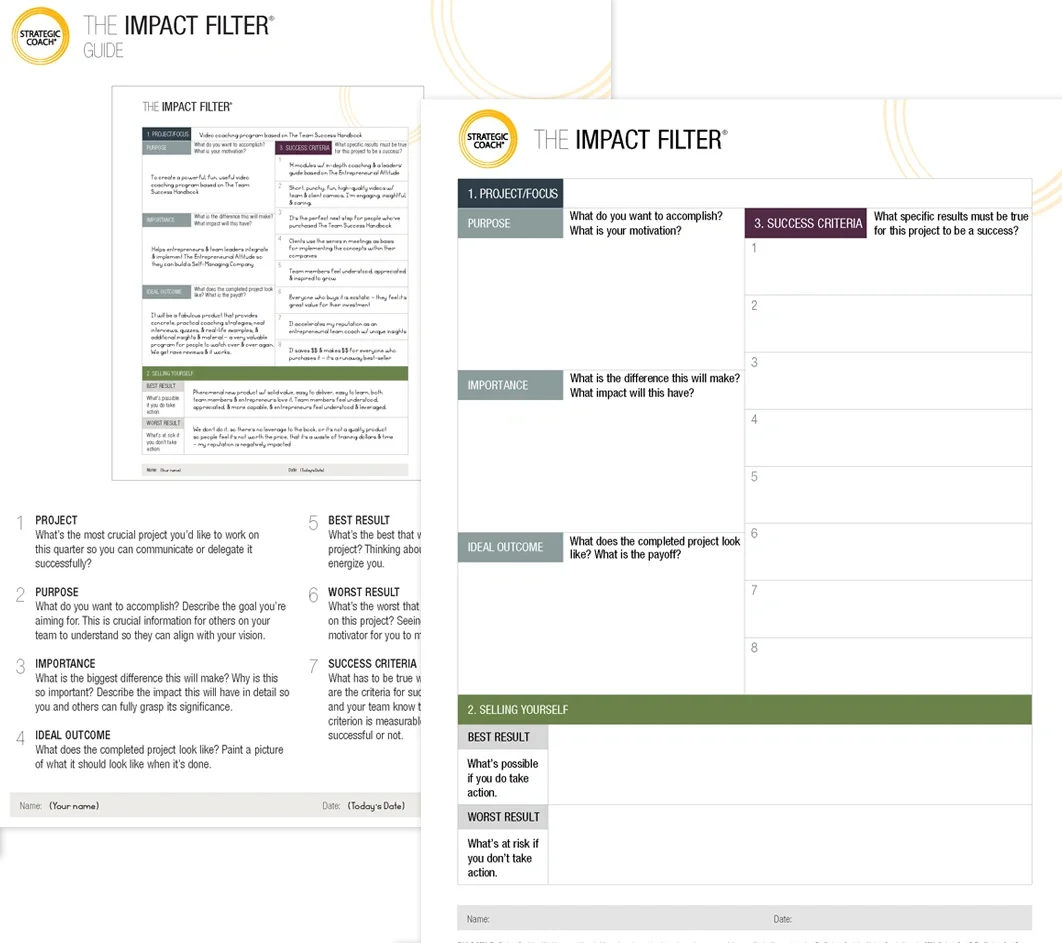

The Impact Filter®

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.