Entrepreneurial Thinking In A Divided World

October 21, 2025

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

Are you navigating division in your business or community? Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff explore how entrepreneurial thinking helps bridge the gap between opposing sides, keeps innovation moving, and fosters practical empathy. Learn how to find common ground, how to stay curious during challenging times, and why focusing on what you can control leads to real progress.

Show Notes:

American identity is complex, shaped more by shared beliefs than by politics.

Deep divisions often go back generations, but most people want similar things: safety, health, and prosperity.

Entrepreneurial thinking is about agency—owning your choices, not chasing quick money.

Entrepreneurship is a patriotic act, showing belief in the country you’re in and its future.

The entrepreneurial journey is a lifetime commitment; few ever return to “normal” jobs.

Genuine curiosity and empathy help bridge gaps between differing viewpoints.

In many ways, being American feels almost like having a shared faith—it’s deep, personal, and instinctive.

Americans define themselves by their nationality, while Canadians mostly just know they aren’t American; there’s less focus on a single national identity up north.

Informed, vigorous debate is healthier than shutting out people who disagree with you.

Find common ground with others; sometimes, a practical approach gets the bills paid and the team moving forward.

Agency and passion, not money, are what keep entrepreneurs motivated over the long haul.

Challenging experiences build empathy, resilience, and a shared humanity among entrepreneurs.

Resources:

Learn about Strategic Coach®

Learn about Jeffrey Madoff

Casting Not Hiring by Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff

Episode Transcript

Jeffrey Madoff: This is Jeffrey Madoff, and welcome to our podcast called Anything and Everything with my partner, Dan Sullivan.

Dan Sullivan: We were discussing when you get into a situation as we are experiencing somewhat in the United States right now, there's a contention, political contention, and it's talked about the most divisive period the United States has ever been through, but actually that was the Civil War. You know, we're throwing words at each other today, but we're not shooting, we're not killing. But the question is, is there a way of bridging the gap between two sides? And my thought was that the great advantage of life in America is new things are going to be created in the marketplace, which force the political sides to actually adjust. They have to kind of constantly adjust. It's hard to maintain a fixed political position when the very landscape, the very environment in which you're living, is changing with new products, new services, new ways of going about things.

So that's been my experience, and I feel that, having lived outside of the United States for more than I've lived inside, that America has more of that than Canada does, for example, or Great Britain, which is another country where I do business and the things are more fixed there, where in the United States, things are changing sufficiently economically, technologically, scientifically, that it keeps things moving.

Jeffrey Madoff: So is it correct to say that you're a foreigner, or do you have dual citizenship?

Dan Sullivan: Dual. Babs and I both have dual citizenship, yeah. And it's useful, because when we go into the United States, we're Americans, and when we go into Canada, we're Canadians. And just solves a lot of bother, but it's interesting. People ask me a lot. They say, What's the difference between Canadian citizenship and American citizenship? And I said, Canadian citizenship is like having a really good mall card. You know, it's like, the parking is better. You get early sales. You know, it's got all sorts of convenience. It's kind of neat.

And American citizenship is like religion and how so much more fundamental … I mean, the belief system and everything. Americans know what Americans are. Canadians know that they're not Americans, and it's a real problem. There's no identity here. Their identity has been defined in terms of the British for a long time, and then their identity is defined. There isn't a really Canadian identity. Except we're not this.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, and I guess the latest version of we're not this is we're not the 51st state. That's not what we're interested in. did that unify in ways?

Dan Sullivan: Enormously. It said we're not the 51st state. Yeah, no, I can just buy the Canadian flags. I have a thing of paying attention to flags, whether there's a lot of flags out, and I would say, up until that incident, the statement when Trump called Canada the 51st state, or suggested that it might be—in our neighborhood, there's about a 15-minute drive until you're out of our area into the next area. And I would say there might be 18 flags. And I counted on Saturday, and there were 43 flags, which I think is a good thing. I think people should fly the flag.

Jeffrey Madoff: Did that surprise you?

Dan Sullivan: No. I think, well, first of all, it happened right when an election was happening. So I think that, you know, we were having a Canadian election. And the Liberal Party, they've sort of based their—who won the election, and they are generally the winners of the elections. Their symbol is very much like the Canadian flag. Actually, it was a Liberal government that brought in the Canadian flag. It used to have aspects of the British Union Jack on the flag and everything, and then they switched over the completely new design. But it just happened that the Liberals adapted more or less the same design for their party at the same time as the new Canadian flag. Was tricky. They're tricky party anyway.

But, yeah, it did. And, you know, I'm very much for people having their flag, you know, like I was really for Brexit because of that weird European Union with all the stars and everything else in England, when you would go into Whitehall, where the government is. And then as soon as Brexit happened, all the Union Jacks came back, and I said, I like the Union Jack better than the European. I don't know what Europe is. You know, I know French, I know Germany. I know I don't know Europe. Never met a European.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, you know, it's interesting, because one could, like, and, well, it's not really, no, it isn't. One couldn't … who was informed, one couldn't—strike that whole thing.

Dan Sullivan: But you know, I don't know what you were going to say, but I could tell I was going to disagree with it.

Jeffrey Madoff: So good point. You knew we were going to disagree about it. Yet somehow, whether we are far apart politically or not, there is a genuine curiosity. We both have a desire to learn and understand that we both have, that we are not repelled by other ideas, and both believe in informed, vigorous debate on those things is much better than just either shutting down or not associating with, and how did we establish that? How did that come about?

Dan Sullivan: Well, we're both interested in a lot of things, okay, but the other thing is that my attitude toward politics is that everybody comes to their political beliefs for very good reasons, and those reasons go back decades and decades. I mean, in our case, they go back, yeah …

Jeffrey Madoff: I would say generations.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, generations. And the only thing is that, for practical reasons, you have to find common ground as you're going forward, because the bills have to be paid. In the case of the U.S., there's some central beliefs that are just American. They're not Democratic, they're not Republican, they're just American beliefs. And, you know, I think we're fundamentally the same on those set of beliefs.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, it's just, I know people who have ruptured close friendships, sometimes even familial relationships, because one side finds the other so intractable that there's no, at least they haven't discovered yet, a way to talk to each other. And I think we all lose.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, yeah. And I think the other thing between two of us, I think my political beliefs are really based on entrepreneurism, whatever is encouraging, supportive of entrepreneurism for those political beliefs, and I don't care where they come from.

Jeffrey Madoff: And I guess I would say to something like that, I guess it comes down to, what do we believe the role of the government is in our lives, you know? And because there are many things that have nothing to do with entrepreneurism, which, by the way, I think entrepreneurism, and we, I'm sure, agree on this too. I've said it before. It's a patriotic act. It shows a belief in the country that you're in, a belief in the future, that you hope you can create, that creates jobs, creates wealth. There's all kinds of reasons for that.

Yeah, I think there's a lot of mythology about entrepreneurship, mainly because that mythology comes from the false notion that you can get rich quick if you're born into the right family. Otherwise, it's hard. You know, you have to work hard to build a business and to sustain a business and all of that kind of thing. And I don't know that there's been a time in recent history where the notion of business has become so much on the forefront, you know, I mean, there were always businesses being created. But I think, and I don't, I'm not sure where it came from. It's interesting that I think a lot of people during COVID became entrepreneurs simply because they had no choice.

Yeah, I think that's happened during, by the way, during financial downturns, like in 2008 with the savings and loan collapses that couldn't find a job, you got to do something to provide and you figured something out. So I think that entrepreneurship, I am one, I value it, but there's other aspects of how we interact as a country and with our government, and what does, what does that do? And what is, what is the role of the government in those situations?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, you know, I actually grew up in a Democratic family. They were Roosevelt Democrats my parents, and then there was eight years when they were for Eisenhower. But everybody was for Eisenhower. Yeah. Okay, yeah, I mean, Eisenhower was a different case. He had been a war hero, and he could have been either side, you know? I mean, he could, he could have been a Republican, he could have been a Democrat when made the difference. And so I grew up in that family, but when I got into business, I didn't really become an entrepreneur until I moved to Canada, and I just noticed that the Canadian government is not really supportive of entrepreneurism, you know.

It's a very bureaucratic country, you know, and I think it has to do with how far north Canada is. I think it's the more you have the chance of freezing to death, the more you need government. You know you have to take care of things. It's Scandinavian. Canada is very Scandinavian. I've been in well, people who live in the north, you have to socialize. You have to do things together, if you try to go your own.

But I'll give you an example that Canada is very, very bureaucratic. And you know that civil servants are really cultural heroes up here, like the Prime Minister, who was just elected, he was the governor of the Bank of Canada, he was the governor of the Bank of England, and he's a bureaucratic rock star. Mark Carney. You’d never see someone like that in the United States, like a bureaucrat, who is a lifetime bureaucrat, who would be a cultural hero. Can you remember any? I can't remember.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, I don't know that I examined that criteria sufficiently to give it …

Dan Sullivan: Well, I think you know you would know them. But here you would know them. There's famous people in Canada, and they were all like the head of institutions, and you wouldn't see that in the United States. I mean, it's mostly entrepreneurial, or it's military. I mean, for a long time it was military. Famous generals, you know, Eisenhower would have been the last of the famous generals. But the other thing is that there's a general trust of government in Canada, where that's not true in the United States, and I don't think that trust in government's been there from the beginning in the United States. I think there was a distrust right from the beginning. And that's a different culture.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, when you've got a country that was founded on revolution, you know, the seeds of discord were already there, yeah, yeah. And so I think that, I think that you're right. I think that the divisions have grown deeper in recent history, although through my lifetime, they've always been there, but I do think that they have grown deeper and more intractable for not good reasons, but because of how we are all so bombarded with information.

Dan Sullivan: The difference is the media coverage of it has changed drastically.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes, yeah. Now, how do you think it's changed differently?

Dan Sullivan: Well, when I was growing up, I would say that if I had to characterize the media in the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s, I think it was left of center. I mean, if you look back, they were tied in very much with the intellectual community, like the universities, they were connected, but there was a general support. Interestingly enough, I think the thing that actually changed the political from the standpoint of how it was reported had to do with radio. That at a certain point, FM became available, and FM became much more the communication medium of university towns. Okay, like almost every university had an FM station.

But the other thing is, the range of FM is so much shorter. I mean, FM goes 25, 30 miles. I think that's, you don't get a really good FM station and they abandoned AM radio stations for the most part, the media, and left it wide open. And the religious right got hold of AM radio, and that's if you look back and see where the beginning of the Moral Majority Rush Limbaugh on that it was because the AM radio had been more left, people didn't want AM radio. They wanted FM radio. Like New York City has great FM stations, all the big university towns. I'm sure you went to college in Madison, and I'm sure Madison had a great FM station.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and I thought of those more to do with, they would play, you know, AM radio had a maximum of, like, under three minutes for the music they played, and there wasn't a lot of talk, yeah, DJs, you know. And over the past probably 20 years, those stations have been bought up or even lost. Within 20 years, they've been bought up and consolidated and all of that sort of thing. And I don't know this, but it makes me think about with the demise of local newspapers. You know, was that an opportunity for radio with give because it's still in this country. I'm not part of it because I don't drive a car to work, but those who will commute to work and all that, you know, everybody wants to hear the weather in the morning, if their teams won. And, you know, it's on kind of a repeat loop, all of that sort of a thing. But I think that the way that news was covered then, it wasn't 24/7, and I think one of the problems with 24/7 is, how do we keep people's attention?

Dan Sullivan: CNN was the pioneer there.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, yeah. When Ted Turner ... I mean, he was an interesting pioneer. He was also thought to be a fool for buying the MGM library that would became the foundation of TCM Turner Classic Movies. And ended up, of course, he made a fortune from that, but everybody thought that was his folly, and then what followed is every major media outlet trying to buy up libraries like what's happening in music now that, you know, Bob Dylan has sold his catalog, and you know all the different musicians that have sold, pop musicians, The Beatles and Michael Jackson and all their catalogs being sold. And it's, I'm wondering, though, if information is being provided by those stations. Because I think local radio stations are doing, I'm not positive this, but I think they're doing relatively well.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, yeah. Well, as you say, newspapers, it was divided between local newspapers and local radio stations. And you know, the advertising, and I mean the newspapers are gone for the most part. I mean, as we knew them, they're mostly gone.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, you and I both had paper routes.

Dan Sullivan: Entrepreneurs got to have that.

Jeffrey Madoff: Along with Kathy Ireland. I mean, not along with her, although that would have made the route a lot better. Yeah. Do you remember on the back of comic books, there used to be that newspaper called Grit, had a guy with a canvas, you know, bag, like I said, deliver the acronym.

Dan Sullivan: Oh yeah, that was, that was, was that a newspaper, Grit?

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, although I never saw it, yeah, real life, but you could sign up for it on the backs of comic books, especially on the other side was drawing a chihuahua in a teacup. If you can draw this, you can make a living as an artist. Yes, I think that's how Da Vinci started, if I'm not mistaken, on the back of a comic book.

Dan Sullivan: It's one of the great heroes of the Grit world. The other thing was that I think what happened there's really interesting thinker that I like watching his—he has video podcasts and he writes interesting books. Peter Zion, have you ever come across him from you, I know, yes, his whole contention was that the world from 1945 to 1991 was an unnatural world. It was the Cold War, essentially, but the U.S. basically did a deal with the rest of the world, that your military strategies would be on our side, and we would essentially bribe you to do that by, first of all, creating enormous capital markets for you to rebuild your economies after the Second World War, the Marshall Plan.

Marshall Plan, and then you could ship your goods into the United States without tariffs, and the U.S. Navy would provide all protection of trade routes around the world. So have the global Navy. It was great navy, but that was so that the U.S. didn't have to go to war with the Soviet Union in Europe. So they built basically a prosperity curtain around the Iron Curtain, and it stopped things.

And so you had everybody who talks about, you know, politicians used to get together. They used to go to dinner. It was during that period, ‘45 to ‘91 that that was true, because you always had the bigger outside enemy. And then in ‘91 the Soviet Union collapsed, without anyone's permission, by the way. But the deal that had been set up was a good deal around the world, but it wasn't a good deal for the United States, except for security reasons. It really wasn't all that good. The U.S. doesn't do that much business with the rest of the world, it's about 10% of the GDP has to do with foreign trade. You know, most of America is just, you know, Americans making stuff, Americans buying it.

So I think that most people's perception of how politics was and how politics was is framed by that 1945 to 1990 period, and it's been falling apart now, with the Soviets gone, and it's gone country to country again. You're back to, you know, lot of issues. It's not that bipolar world that we had before, and I think that has a lot to do with what domestic politics are like. It's that … I think things have become more fractured.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, that's for sure, you know.

Dan Sullivan: But if you read American history, it's very contentious. It's a very contentious history.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, god, yeah, yeah. Although I think that in total, if you look at the history of most countries, it's a very contentious world. And I think that the old stories and the mythologies we know better now, and I think that a lot of the distrust has gone away, as the curtain has been pulled back on a lot of different activities, have revealed things that may have been going on before, but we certainly were not aware of it. And I was going to say when I was in the fashion business, when I was designing and manufacturing, which was in the early to mid ‘70s at that time. Can you guess? I don't know if we've spoken about this before, but can you guess what percentage of fashion goods, apparel, shoes and so on, what percentage was made in the United States, and what percentage was and what percentage was sold?

Dan Sullivan: You mean American made goods? How much of the market?

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes, how much of the fashion market was made in United States at that time?

Dan Sullivan: I don’t know, 50?

Jeffrey Madoff: 95%

Dan Sullivan: Wow, wow.

Jeffrey Madoff: And by the 80s, there was 5% was made here. And you know, fashion, it's interesting because there's a huge gap between the images you might see if you look at Vogue magazine or the red carpets and the desire for cheap labor, which is, you know, what the fashion industry when you go to The Gap, when you go to, you know, all these massive stores, you know, things are made in China. They're made in Cambodia, Turkey, Vietnam. All of that dramatically changed. And I got out of that business, not because of that, because another opportunity getting into the film business surfaced, and I found that at that point more interesting, but the change when I used to come to New York—Did you used to come to New York much like in the in the ‘60s and ‘70s?

Dan Sullivan: ‘60s, started doing it at the end of the ‘70s.

Jeffrey Madoff: It was going through the garment center. That was really interesting, because you would hear Yiddish, German, Italian, Greek, all these different languages. You'd see all these people, these cavernous restaurants that were in the garment center, people that looked like they were never young. And you'd see many newspapers, you know, they'd be selling, you know, the Jewish daily forward and Il Giorno from Italy and all of this. And it was this truly the melting pot. And the fashion industry was, the apparel industry was a way to enter into the middle class at that time. And there was a hustle and bustle in the streets and people pushing racks, and it was just so vital and active.

Dan Sullivan: So where was that 15th Street?

Jeffrey Madoff: No, no, basically from like 34th Street to the mid 40s, low 50s, and which avenue, so would be on Seventh Avenue for the most part, and Broadway. So I had offices in the Empire State Building, which is 34th and 5th. And then I had offices at 1407 Broadway, which is around 40th Street and 1411 Broadway, but it's all just offices now. There's no manufacturing, none of that is going on. And that was an essential middle class entry point for immigrants, you know, coming into this country, yeah. And it just changed dramatically, not unlike the film business, yeah, where the hustle and bustle of the major studios, it's now just offices.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I think that a couple of things that facilitated that. One is that China came into the game in the early ‘80s after Nixon went. And visited in China with Kissinger early ‘70s, but China came into the game. But the other thing was, the very interesting creation of the Vietnam War was the uniform container for shipping. That was, do you know the background to that?

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, yeah.

Dan Sullivan: Well, the Vietnam War, they shipped enormous amounts of materials into Vietnam, and the harbor down at the bottom, where Saigon was, was very shallow, and they couldn't get the big ships in and so, but they made a rule that if you shipped anything, it had to fit in a container. And they could just put lawn piers out, and the containers could come in, and within about five years, just because of the U.S. Defense Department requiring that everything shipped, all of a sudden, the worldwide shipping industry adapted these 20- and 40-foot containers, and it destroyed the longshoreman’s union, actually, because you could put piers anywhere.

They used to have to take every piece of something out of a ship and put it into a warehouse, and then it would put in another ship. And it was like an ATM for the longshoreman’s union, you know, which were controlled by the mobs, basically in New York and Baltimore and elsewhere. But that thing of the uniform container thing just globalized trade, because you could have on board ship, you could have boxes going to 100 different places, you know, and boxes could be filled up with materials from 100 different companies, you know, as they did that, and it was all tracked electronically and everything like that.

So I think that really changed the clothing industry enormously. I remember I went to Manchester, New Hampshire. Manchester was where Levi Strauss started. The big Mills for Levi Strauss were in Manchester. And if you go there, it's quite remarkable. They have these amazing brick buildings, and they probably have 20 or 30 of them, and fortunately, they haven't been torn down. But this was part of the big fabric industry, which was mostly in New England. It was mostly New York, Boston, that area. And then they had a strike, 1927,1928, and overnight, Levi shipped everything to North Carolina and South Carolina. It all went south. So that was probably the first jump where you were going from one place in the United States to another, going for cheaper labor, I suspect. And then in the ‘70s and ‘80s, probably another jump, you know, overseas, where that went.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, you know, it became part of the branding, some who probably put Made in the USA.

Dan Sullivan: That's coming back, by the way. I mean, it won't be major, because there's still economics involved here.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I don't think that the global economy existed back then the way it does now. You know, that's probably the most compelling reason why, except for some players, many people realize that that mutually assured destruction actually gets everybody, you know, it's not a great idea to do. But Margaret, my wife, went with Halston, who was the first American designer, and he was a guest of the Chinese government. And he went there with 20 some models. I mean, just this incredible entourage. And he was the first American designer that, you know, started doing business over there, and it was as a result of, you know, Nixon opening up trade relationships and so on. So, yeah, you know, politics and economics are never very far away from each other, and the things that are done to help industries get a foothold, or if they have enough money to pay lobbyists to get them a bigger foothold, or whatever.

It's just kind of fascinating how it all works and how interconnected so many things are. And that the term which I didn't hear until I don't remember when I heard it the first time, but supply chain, it was a lot easier before everything was going overseas. And you know now it isn't, and that's, you know, each radically different thing that has happened and affected businesses. There were things that happened as a result you couldn't imagine that actually then created new jobs. And you know, other ways for people to make money, which is also kind of interesting, because everything becomes the next big threat or the next big opportunity.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, yeah. Well, the other thing is that, as entrepreneur of owning your own company, you're constantly paying attention to, how does cash flow happen over the next quarter? You know, where's the money coming from? And you're adjusting your communications. You're adjusting your teamwork. You know, you're adjusting outside relationships with vendors and everything like that. And there's millions of business people who are making millions of decisions, and they're all doing it for very specific, fairly short-term reasons.

Jeffrey Madoff: Did you become an entrepreneur because of, how can I say it, the lure of entrepreneurism and the hopes of making money, or did you become an entrepreneur because you wanted to have more agency over what you did?

Dan Sullivan: The latter, and it was because I wanted to do a particular type of activity that I thought had—coaching, you know, like I was already doing it, you know, doing it without getting paid for it. You know, it was a particular type of activity that you could help people get clearer and more confident about their future, if you ask questions, and you could document it in a certain way, graphically, you could document it. You could do it in text and everything like that. So it wasn't about, I mean, I think you made money so that you could keep doing it. In other words, it was just an activity that I thought I would love doing.

I didn't do it enough that I knew I loved it, but I got a sense of it, and I can remember talking to my creative director, who was the half owner of the ad agency. And I said, I've got this idea of a particular business I want to create, and he's the one who hired me in the first place. And he said, If I say no, I don't want you to do that, will it make any difference? And I said, no, it won't make any difference. I'm going to do it. And he said, well, he said, I did the same thing 25, 30 years ago with advertising. So he said, how could I be against it? And, you know, but it's always been about the activity. It's the passion for the activity. And then how do you pay for it? Right?

Jeffrey Madoff: The same with me. It was not about, I mean, I had to make money to survive, of course, and keep the business going, but to your point, it's so you could keep doing what you wanted to do. Yeah, and that's what it is with me too. That was the biggest thrill to me, is having that kind of agency over what I did. And that's what was the lure was, not to mention that. Why do people always say not to mention, then they mentioned what they were not going to mention that? You know, my parents were entrepreneurs, and so that wasn't an unusual thing for me to want to do, you know, to somehow create my own businesses. That's what they did.

And so I was used to that, and probably had more familiarity with how a business is run on a minor level, you know, but seeing my, hearing my parents talk about business at dinner, in the day's receipts, and, you know, all that kind of stuff, it kind of the main lesson you learn is, if you want to keep doing it, you got to have more money coming in and going out. There's a story of my great grandfather who I never met, but he was in New York, and he would, on the Lower East Side, and he had a wagon, and he would buy socks for $1.50 a dozen, and then he would sell them for $1 a dozen. And my great grandmother said to him, how do you think we're going to stay in business if you keep selling it for less than what we paid for it?

Dan Sullivan: With volume?

Jeffrey Madoff: That’s right. Volume, that's right. But you know, it's interesting, because

Dan Sullivan: I always wondered where that story came from. Now I know.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, it was actually my great grandfather, [inaudible] was his name.

Dan Sullivan: What are we talking about? 1870s, 1880s?

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, something like that, 1890s even. But, yes. But you know, the thing is, whether we're talking about, we're doing what we do, because we love doing it. And the initial thing was not, I'm going to make a fortune. It's, I want to do this. This is cool.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I think it's why both of us are fascinated with theater, because you would never do it for the money.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right.

Dan Sullivan: No, it's such a risky business. I mean, unless you you might find one person out of 20. You know, I'm going to go into theater because that's where you make the money. I can't believe it. It's got to be a deeper passion than that. I mean, and I have—we've had 25,000 entrepreneurs, you know, who were in the Program for at least one year. But the ones who do it for money don't stay long. Where the driving passion is money, I can't remember one that really impressed himself or her. That's mostly him, himself on me. You know, I said there's a great entrepreneur. It's always the agency is really the main thing. And it's the main language on how different entrepreneurs talk to each other. It's the agency you have over your future. That's why they do it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and, you know, as we're talking about this, and even the story about my great grandfather, it's, there is a sense of empathy because we've both hit on hard business times, and the ability to both recognize that and to be able to also laugh about it. Because, fortunately, things worked out ultimately, but not without obstacles along the way.

Dan Sullivan: Not without mistakes.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right, that's right.

Dan Sullivan: I've never had a mistake I didn't pay for.

Jeffrey Madoff: No kidding, yeah. Otherwise, how would you gage it? Right?

Dan Sullivan: Somehow, I never had a free mistake.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right, I haven't either, because then I wouldn't have recognized it as a mistake, right? Yeah, I think that that kind of curiosity, that kind of empathy, in terms of knowing what other people's struggles are, these things come under the umbrella, to me, of like a shared humanity, and that shared humanity, to me, is something that can also help narrow a divide. I will, I'm sure, go to my grave thinking about that and thinking about because, you know, I like the fact that I'm pretty comfortable talking to just about anybody, about anything, and that I don't assume anything.

I was going with my girlfriend at the time, this is back in 1970, went into the mountains of Colorado, and we were hitchhiking, hiking to her brother's place, and hitchhiking in the mountains. Then I had hair. Then it was down to my shoulders, and there was not much traffic going up there. And what was going on at that time was certain mountain picture being blasted out because it was becoming a real ski center around this area in Colorado and Breckenridge, which is where we were going. Anyhow, there's a truck. You know, pickup truck slows down when we're hitching and maybe there was a car every 20 minutes or something.

And so I said to my girlfriend at the time, I'm going to get in first. So if anything happens, I'm next to him. And it was “America: Love her or leave her” on the bumper sticker. And you know, it looked dicey, but we were sick of being out there. No not enough traffic anyhow, again. And we started talking, and he said, you know the .45 Magnum is? I said, yeah. He said, you ever see one? I said, I mean, in the movies? And he reaches under a seat as he's driving, and he pulls out a .45 Magnum, holds it like that. Said, this is a .45 Magnum. And Vicky was getting really nervous, so was I. He said, you know, this is the only handgun that can stop a truck. You can put a hole in an engine block with it. I said, I guess that's useful if you're hunting trucks. And he laughed, and I said, here, and he handed it to me.

He was just showing me a prized possession. There's nothing threatening about it. And so you know, which is a big gun. So anyhow, he goes on, and he said, if you guys had anything to eat today yet, and we hadn't. And he said, we're going through this area where I work. We'll stop and get something, then we'll continue to Breckenridge, and we go in and, you know, he had tattoos before they became a fashion statement. It was if you were in the Marines or, you know, something else, or not part of the services, but part of a gang.

And we go into this place. And so people start saying stuff about me because of my appearance and her, and he was clearly a person with some influence. And he said, shut the fuck up. These are my friends. And so we sat there and we talked a bit, and he said, you know, Jeff, I don't have any use for hippies, but you're all right. You two are okay people. I said, well, thanks, you're okay too. But did you ever think that maybe a hippie is just somebody with long hair that you haven't talked to before? And they said, you have a point. And he drove 30 miles out of his way to drop us off. Really nice guy. And I felt like that was a real moment.

And it was interesting, because I think those moments you build on those little shared experiences and those kinds of things, because I think most of us want the same things. You know, you want to be safe, you want to be in good health, you want to prosper. You know, we all want those same things. I think the way some of us try and get it is different, and I'm not being Pollyanna here. I mean, I've always found that, and I've been in a number of situations that could have gone the wrong way, but fortunately, didn't. And so I find it really interesting, because ultimately, he was curious about us and I was curious about him.

Dan Sullivan: Well, he wouldn't have stopped if he wasn't.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right, yeah.

Dan Sullivan: I mean, he had a choice to stop and you had a choice to get in or not get in. He had a choice to stop. So you both did that.

Dan Sullivan: We stopped. By the way, I was wondering. He even paid for lunch.

Dan Sullivan: I think that should be a requirement. The one with the .45 Magnum has to, yeah. But he was also sending a little message just by showing you, because, you know, drivers have been killed by passengers, you know, like he was just letting a little signal by showing you the gun that I can take care of myself and everything like that. I understand that.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, there were three at that time, because of all the development that was going on. There were three distinct groups. There's the construction workers, which he was one of. There were the hippies who had, you know, places up there, shacks and so on. This wasn't a wealthy area. It was an area nobody was so you could live really cheaply. And there were the wowboys. And the common enemy to with the cowboys and the construction workers were the hippies, but neither of those two groups liked each other, either.

And you know, that evening, we were at this bar, and it was literally like from the Old West. It was like this cabin with boxes of beer bottles out on the front wooden porch of the cabin. And it was an interesting, interesting place. And there was a guy who was maybe 6’2, 6’3, and weighed about 280 pounds. Of course, his name was Tiny. He had a scalp lock, like just a single braid. His head was shaved. He was Asian, and as we're having a beer, all these lights come into the place, the headlights, and you hear car horns honking and all that kind of thing. So what's going on? And my friend's brother said, this happens all the time. This is what happens.

And I hear crowbar like hitting the wooden deck outside this bar, you know, with the baseball bat or crowbar, and there's like, seven or eight guys, three pickup trucks. And they said, this happens all the time. So what happens all the time? And they said they get drunk, and then they come up here and they want to beat people up. I said, what we're going to do? He said, just watch. And so as the yelling starts and all that, and then Tiny pushes away from the bar and walks out. I walk out behind him with a few other people. And these guys literally have, you know, baseball bats and crow bars. And Tiny says, I don't want a problem. You go, no fight, no problem.

And so one of them, they start to circle around him. I said, what's going on here, man? And he said, just watch. And a guy comes up to Tiny and he brandishes his crowbar. And said, I’ll fucking kill you. And Tiny knocks his nose up into his forehead. The guy goes backwards, another guy comes up, and this is like kind of a movie, and he takes three guys out in less than 10 seconds. It was insane. And he goes, you go home now. No more trouble. He picks a guy up and throws him in the pickup truck, and the guys leave. And I said, this happens all the time? They said, yeah, it's happens all the time. And Tiny always kicks the crap out of them, and then they want to challenge him again.

And I said, what about the construction workers? And he said, they're a lot smarter than the cowboys, and they never come over here and cause a problem. But you know, these people don't even know why they hated each other. I didn't mean to go on that reverie, but that brought up that memory to me after the truck.

Dan Sullivan: Well, it's this or television, Jeff, this was entertainment. It's entertainment, yeah. Well, you know, the world is not as we know it in the United States either. You know, you have that country. And I think one of the things that has really happened in my lifetime is that we got used to a particular world, okay, and then it changed abruptly. The big change was the Vietnam War. I think during that period, that was the big war. I mean, you had the Korean War, you had other wars, but the Vietnam War was a real dividing point, okay, because it happened with the biggest population that ever happened. It was the baby boomer generation that got there. And, you know, I went, you know, I was drafted in ’65, I went two years, never gave it a thought, came back and never gave it a thought, because I had three brothers that were in the military, and I never gave it any thought.

And I went through college, and everybody was talking about the draft and everything, but I never gave it any thought. So it never had any particular impact on me one way or the other. You know, so, but it really, really did. I mean, now every once while, I go back to a college reunion, and they're still living the Vietnam War 40 years later, the ones who were against it, you know, and I meet Americans who moved to Canada and, you know, it happened in the 1960s and they're still talking about it as a fundamental experience in their life. So I think that was a huge division that happened right then.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, there are many that think we're still fighting the Civil War here. You know, beliefs handed down generationally. I don't think it's so simple and binary anymore, but there are deeply-seated prejudices that, you know, I think we will be better if we can get past these things. But I think the U.S. is just a contentious country.

Dan Sullivan: Well, I think you're right. I mean, it's just what they're being contentious about. That changes, but there's a contentiousness there.

Jeffrey Madoff: It's like the movie with Marlon Brando, The Wild One, about the motorcycle gang, and they go into the diner. And the owner of the diner said, “What are you guys protesting about?” And he goes, “What do you got?”

Dan Sullivan: I did an AI search of what are the 10 most divisive, polarizing, contentious periods of American history and our present age is number 10. There were nine that were more contentious in terms of, you know, I mean, like the 1880s and 1890s the amount of violence, killing and everything that happened, you know, because you had the collapse of the agricultural economy over about a 30-year period, there were about five depressions from the 1880s to about 1910. I mean complete depressions.

I mean, everybody talks about the Great Depression. There were depressions about every seven years, people lost their entire livelihood, and then they had the issue over the, was it going to be gold or silver was the currency, and they just made a decision, it's going to be gold, and everybody was holding silver. The value of silver went down by 90% and they lost all their fortune. And, you know, there were riots and, you know, so it's been that way from the beginning.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. I mean, I don't think we're obviously, I think we've entered into a new era. That's how that is going.

Dan Sullivan: I think we're throwing words at each other, though, but we're not throwing, you know, weapon, and we're not using weapons, really.

Jeffrey Madoff: I think that there is such a thing as fighting words, and there are words that have great meaning, and those words, when turned into policy, can have a strong impact. And to me, it's critical thinking and the acquisition of knowledge as a result of curiosity and wanting to know how things go, not that necessarily figuring anything out, but I think that's a really a much more worthwhile pursuit than trying to vanquish parts of the population. Yeah, you know, but it's really interesting, because I do think there is a greater shared humanity, but it makes it impossible to recognize that there's such a den of what's going on.

And I watched a fascinating documentary on American masters. Do you know who Hannah Arendt was? Her major work was called The Banality of Evil. And that's as a result of her covering the Eichmann trial at Nuremberg. And it's really, really fascinating in Jerusalem.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, in Jerusalem, it was Eichmann.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes, yes. Thank you. She wondered why otherwise decent family people, working class and so on, how could they go along with the horrors of what happened in Nazi Germany? And you know, Eichmann was one of the famous, “I was just following orders.” And one of the prosecutors said, “So if you were given the order to kill your father, would you do that?” And he said, “Yes, I would.” And she landed on this notion, which I think is true of the banality of evil, and how it's just easier to go along. People do things because other people do them. And there's not necessarily much among the masses, not much thought about what they're doing. And people who stand to gain power, wealth, which is also power, but all these things, those can when the right things are orchestrated and the right fears are stoked, the wrong things can.

Dan Sullivan: The other thing, it was very interesting. I went to Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Museum in Jerusalem. And there are two things that I found interesting about our guide. And the guides are just, they're amazing, from what I learned from him about being a guide, because they have to know religion, they have to know history, they have to know economics, they have to know politics, they have to know archeology, everything, and they try to get a read on you as a customer of their services. They try to get a read, you know, where is this person? Because they have to adjust.

But I knew a lot, but I went to the museum, which was really interesting, and it was absolutely quiet in the museum because you have earphones, they don't have public tours of people talking or anything. It's all earphones. And they said that the Germans were very, very clever. They would just push and see if they could get away with the push. If they got away with the push, they'd give another push, another push. And they say, you know, it probably be better if your children at school weren't, you know, the teachers weren't Jewish, because they don't really know German culture. They don't really know and they would see if they could get away with that.

And then said, you know, we just went through the Depression. And wouldn't it be better if the shops that you went to, the stores you went to that they were Germans, they weren't Jewish, and they just started creating this separation. But there was no big move. I mean, the biggest move was Kristallnacht. You know, when the Kristallnacht happened. But that was move 51. There had already been 50 moves before that, and where they did that. And the other thing was that the Eichmann trial changed everything.

And the guide I had, he said, you know that the Sabras, the people who had been two or three generations in Israel, you know, who had come over as part of the movement out of Europe in the 1890s, 1900s, 1910s, and a lot of them had been born, and a lot of them had been there for centuries. Lot of the Jews had been there for centuries that they had very little respect for the refugees from the Holocaust. They were like second class citizens. And they said, how could people let them? How could you be pushed around like this? How could you put up with it and everything else?

And when Eichmann and they sat, and it was national TV, you know, everybody was just fixated by this trial, which went on for quite a while, and for the first time, they began to realize it that they wouldn't have been able to put up with the kind of pressure that the Germans had put on them. He said, that was a great moment, and that Eichmann trial was very, very important experience for the Jewish nation. Yeah, and when you go, you know, they have that garden. They have all the trees for the people who had, for no gain, had taken the great risk of helping save Jewish people and hid Jewish people and everything else that he said, they have a rule that no one can say how they would have performed in those situations. You could say, well, I would have taken care of my… he said, you don't know. He says, nobody knows you. You only know in the moment how you would respond to it, right?

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right, yeah, I think we live so much in an uncharted world of mythology and false beliefs, because I think that the recognition of certain things is frightening to people, to many people, and they don't even know why it's frightening, whether it's the demographics of the population changing, you know? I mean, supposedly this is the melting pot, you know. Are we going to continue to attract the best and the brightest in the near term? Anyhow, that's a big question in terms of research and science.

And just, you know, who knows. We have gone through periods before, and I'm sure we'll go through periods again. I think this is a very difficult time on many fronts, because I just think it's hard if you don't understand, or don't care, to understand what the other side is thinking. I think what that does is just build the walls higher. And I think that those who are curious and those who recognize our shared humanity are the people that want to bridge those gaps. I hope that happens. In the meantime, I want people to buy tickets to the play.

Dan Sullivan: And let's get the book down. Yeah, I was at a party, a garden party, two houses down, and we had just come back from the cottage, and, you know, they're all Canadians here and there. And they were interested, because, you know, they knew that we were dual, you know, and they were saying, this is bad and this is bad and this is bad. I said, yeah, but on the street, we have it pretty good, don't we? I mean, look at the beautiful weather. You know, we're having garden and, you know, everybody's talking, but they were fixated on what's wrong. And you know how things are going, you know, I said, a year from now, probably nothing that's going on in the world is going to affect you at all, you know.

Jeffrey Madoff: So what do you think is the takeaway today?

Dan Sullivan: Well, my sense is that I constantly look for where the common ground is, you know, with anyone that I meet, you know, and some people, there isn't much, there isn't much. And you make it short. You make the discussion. But my sense is that I think to answer the question, why we, in spite of having different things—one is that politics is not that important thing in my life. You know, I've got many other things that are much more important than politics, so it's not a defining issue in my life. But entrepreneurism is very central. And we have entrepreneurism in common, you know? And that's a rare experience. Not many people have the entrepreneurial experience.

It's about one out of 20 of the adult population make their money in a way that could be, in any way, thought about as entrepreneurial. So I think it's a unique group of people, and I don't know many people who aren't entrepreneurs, you know. I think that's the central issue. And I think entrepreneurism is a very, very clean way of approaching your life, you know? I just think that there's not many people who have the stomach for this particular type of activity and are willing to go decade after … I mean, that's a life sentence, too. You do it for 10 years and you're not going back to anything resembling normal life.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. Yeah, because you don't know how anymore.

Dan Sullivan: No, and they won't have you.

Jeffrey Madoff: It's almost like you've been raised by wolves.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, yeah, and everything. So I think it's really that, plus we have a passion for theater, so you just look for what's in common.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think that we have managed to fold that into the anything and everything of Anything and Everything, that is correct. Thanks for joining us today on our show, Anything and Everything. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend. For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

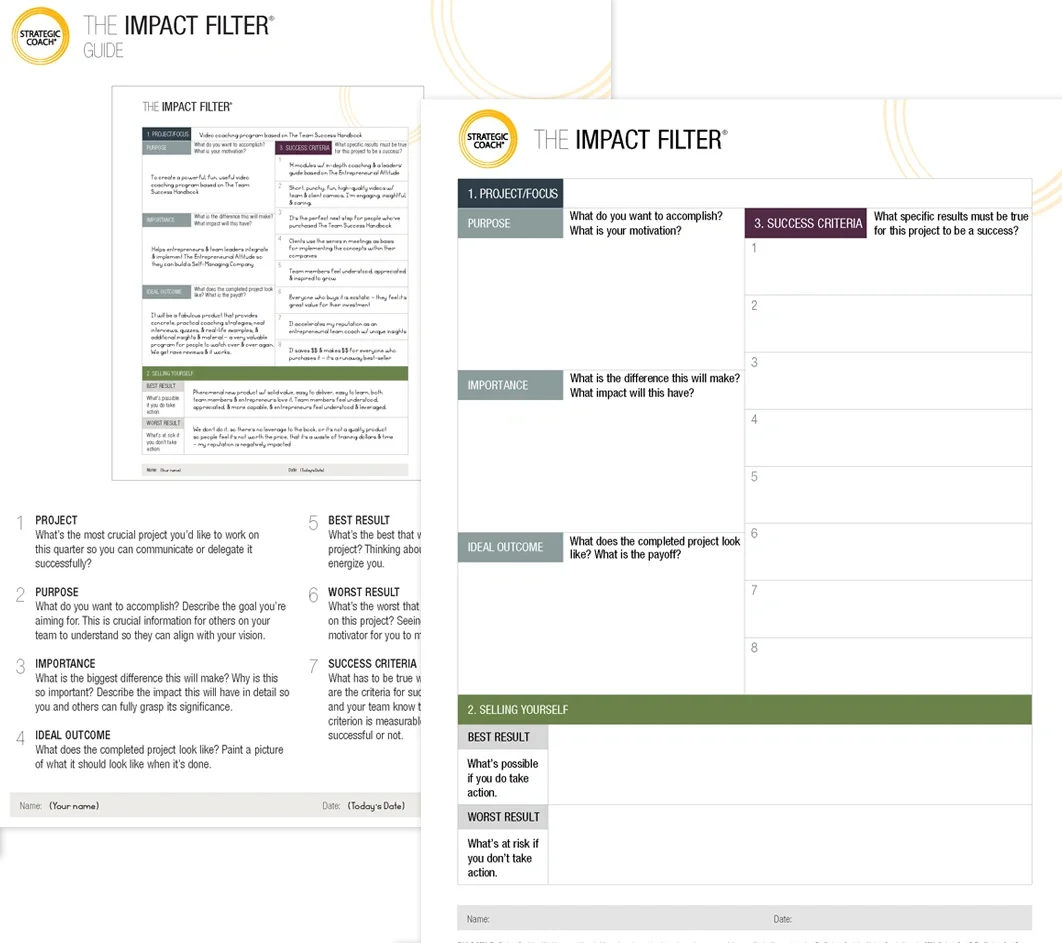

The Impact Filter®

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.