Why Bigger Isn’t Always Better In Business

November 11, 2025

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

Is growth always the goal, or is there wisdom in slowing down? Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff share how real breakthroughs happen when you pause, build new capabilities, and stop chasing cookie-cutter success. True progress as an entrepreneur means playing your own game and having the freedom to shape your life, not just your business.

Show Notes:

Growth comes in two forms: expanding outward and building new capabilities internally.

It's difficult to maximize your existing capabilities and create new capabilities at the same time.

Lasting breakthroughs often start when entrepreneurs get bored and look for new challenges.

Every capability, even the ones learned under pressure, adds to your entrepreneurial tool kit.

Treating your capabilities as unique assets, rather than just checking off boxes, leads to bigger, better opportunities.

Strategic Coach® draws inspiration from the entertainment industry, not the corporate world.

Not every business needs to scale endlessly; staying small can give you more freedom and satisfaction.

A tightly scheduled entrepreneur can’t transform themselves.

Most people want to retire because they need time off, but entrepreneurial growth happens when you realize you can take time off now.

If you want your business to support the life you want, be deliberate about choosing both growth and downtime.

Resources:

Learn about Strategic Coach®

Learn about Jeffrey Madoff

The Entrepreneur’s Guide To Time Management

Your Business Is A Theater Production: Your Back Stage Shouldn’t Show On The Front Stage

Who Not How by Dan Sullivan with Dr. Benjamin Hardy

Always More Ambitious by Dan Sullivan

Episode Transcript

Jeffrey Madoff: This is Jeffrey Madoff, and welcome to our podcast called Anything and Everything with my partner, Dan Sullivan.

Dan Sullivan: Jeff, we were talking about growth, especially entrepreneurial growth, and is it desirable to always be pushing for growth? And I live in a big entrepreneurial ecosystem here at Strategic Coach. And my attitude is that in an entrepreneurial company, there's all sorts of different areas that can grow. But I see it as there's internal growth and outward growth. There's growth of results and there's growth of capabilities. And oftentimes you have to not push as hard for economic growth in order to grow new capabilities, which will then create much greater growth at the next cycle.

So that's sort of my attitude is that you, I call it development and expansion. It's hard to be maximizing your existing capabilities and creating new capabilities at the same time. I think there's sort of a loop. You go up, you maximize what you have, and then you go back and you develop more capability, which you'll maximize later.

Jeffrey Madoff: All right, let me ask you a question. You have a very successful business with Coach. There is a high likelihood if you wanted to, which I know you don't, but if you wanted to either sell the company, put it on the marketplace, or any number of things that you could license and do separately. But it's always struck me, and it's more reinforced since we've gotten to know each other over the last 15 years or so, is more important in growth to you is doing what you want to do. So have you pushed it? I mean, you've had a natural growth of the company, but what was the priority? What was the driver?

Dan Sullivan: You know, it's an interesting thing. My approach is to always be creating new things. So there's been a constant growth of new offerings every quarter, and that's right from the beginning. So we're in November to be 36 years that we've done it, and it's been continually profitable. You know, we've had a couple of flat years, ‘08, ‘07, when the subprime crisis was mainly in the United States. And COVID, we had a flat year, but generally the years have been profitable, more than generally, almost all the time.

But the big thing is that my big emphasis is that in the coaching world, and this is an observation I've made because I've been in the entrepreneurial coaching world as long as there's been an entrepreneurial coaching world, you know, since 1974, that the tendency in the coaching world is you get a fixed cookie cutter, and then you just pump out cookies for the rest of your career. And my attitude is that there are some things that people would like to see all the time, and you keep them the same, you know, particular ideas, particular concepts, and they like going back over them again. They like having them reinforced.

But you always have to have something new, you know. And that goes into your world, two worlds that you've been in, the fashion world and also the entertainment world. There are some oldies but goodies that people always like, but they also want to see something new all the time. So you got to satisfy both of those. And my greatest pleasure is creating the new stuff.

Jeffrey Madoff: Which are the tools, right?

Dan Sullivan: The tools, yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: But, you know, in terms of, let's take the tools, do you create new tools because you feel the pressure that you have to create it to keep your business growing, or is that a by-product or development of capability as a result of you doing this that you derive pleasure from that?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, at this stage, I would find it hard to separate the two. I mean, we have a reputation in the coaching world of being the company that constantly creates new things. And I want to maintain that reputation. The reputation is very important. But for me, it's just the pleasure of creating something new. And a great gift of COVID was that in order to make up for the fact that people couldn't see us personally for, you know, basically two years, we were always a live event company. You know, you came. You were a member of a workshop group and you came at least four times a year. And that was taken away by the COVID restrictions.

So what we did is that we maximized the use of Zoom to give them little short workshops, like two-hour workshops. And that has turned out to be a tremendous capability. It was forced upon us, but we took advantage of it. And the thing about it, it allowed me to speed up the production of new tools where I could, for example, I have three of these two-hour sessions next week, and I'll have two new tools that I can just test out. So it speeded up the process of just create a new tool, try it out, see what people think about it, you know. And I've never had one that got rejected from that process, but I've had a lot that got improved by that process.

Jeffrey Madoff: But what I'm wondering about is, you love what you do.

Dan Sullivan: I do.

Jeffrey Madoff: And that you derive fulfillment from it. There's a status that comes with that. And there's the financial reward that comes with that, too. So you've got a great setup. That's highly desirable. If you put the pressure on yourself that you wanted to grow your business every quarter by X percent, or every year by X percent, would you feel motivated to do that for the sheer ending of, yes, we're up 18% this year and we were up 12% last year, or is it, I love what I do, I do well at it, and there's a natural growth that comes of it, but my focus isn't just on growth?

Dan Sullivan: My focus is on creating the new tools.

Jeffrey Madoff: You have turnover in your clientele, so there's always new people that you're meeting also, which is, I think, probably a real pleasure too. That's why I enjoy that in what I do. What I'm trying to get at is there's so much emphasis on growth in business all the time. And I think that there's a lot of businesses that are fine the way they are. You know, like a good friend of mine is an incredibly talented musician, and I don't use this term lightly, as an arranger, he's a genius. It's the Ed Palermo Big Band I told you about, who I hope we'll see together at some point.

And we were having a conversation, and I said, so, Ed, you teach at a school of music. You also have your private clients. You do two gigs at two different places that you like working at. But have you really ever had the desire to really build this into something big? And he's one of these people that you would call a musician's musician. He's just so good and so incredibly creative. And he said, no. I said, I'm just curious, why? He said, because I'm very clear about what I love doing. What I'm doing allows me to do that. So has that enabled me to amass great wealth? No. But has it enabled me to do what I love doing the way I want to do it? The answer is yes.

And I have another friend who could have been an Olympic coach or a high-level college coach. He's a high school coach in track and cross country. He was solicited, he was even brought to Germany to do coaching, you know, for this summer thing. And it's really interesting because we've been friends since we were little kids. And I'm friends with his brothers, too. And Lee happens to be incredibly satisfied and fulfilled with what he's doing. And he has no desire to try to make it more so. And I didn't see it as, well, he doesn't want to take on the challenge. He loves being the big fish in the small pond, and that's very satisfying to him. And so I wonder, in seeking oftentimes that elusive idea of fulfillment and the pressure that there often is for growth, how do you bridge that? I mean, it sounds like you've united it all.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I think, you know, and I'm just using your question here. And one of the reasons why entrepreneurs come to Coach is to grow. And, you know, I mean, there's a scoreboard issue here, you know, revenues, value of company, you know, profitability, and that; these are all measures that they have and their sense of growing is doing it. But one of the things, for example, that we are probably kind of unique in is that back in the, this would be late 80s, we just noticed that if you took more free time, you made more money.

And we have this marketing line, double your free time, double your income. Okay. And it was a hit. I mean, it was an enormous hit when we first started. And for the most part, we kind of worked out a way of thinking about this, that it actually happened. And that most of the reason why the entrepreneurs who were coming to our workshops is that they had maxed out. They couldn't work harder and they couldn't work longer. And, you know, it had cost them health, it had cost them relationships, especially marriage and everything.

And I said, you know, you're all operating, you're entrepreneurs and you made a decision that you're going to be an entrepreneur. And you separated yourself from the employment track. You know, at a certain point you made a decision that all my friends are getting jobs, you know, and they're employees, but I'm not going to do that. I'm going to have a direct relationship with the marketplace and I'm going to, I'll be responsible for how much I get paid. But they did this in their mind. I'm talking about how they were looking at it so that we could talk to the conversation they were already having with themselves, is that they would have to work harder, they would have to work longer, and they couldn't because they had maxed out.

And we said, you know, I don't base our company on the corporate world, I base our company on the entertainment world. And I said, entertainers have a totally different time structure than corporate people do. Corporate people have weekdays, weekends, you know, vacations, not much and everything. Actors have performance days. They have rehearsal days, and they have off days. They're between productions. So we're going to have three days.

We'll have a Free Day. A Free Day is where you don't do anything related to business. You have a Focus Day when you're 100% on the business that really produces the results. And you have Buffer Days, and Buffer Days are back stage days. changing things, learning new things, you know, everything like that. But you're not required to produce results on those. What you're doing is you're actually simplifying things where they've gotten too complicated. You're bringing on new team members and they have to be brought into the system. And it really, really worked. And just that separation really, really helped.

And what they found was, I gave them an example once. I said, you've scheduled a vacation, okay? And you, at the last minute, you say, you know, that five days I was going to take on vacation, If I didn't take them and I actually did what I do, I'd be further ahead. And I said, I want you at least once to resist the temptation not to take the vacation days, but make a list of everything that you would do while you were on vacation if you didn't go on vacation and write it out and then put it in a place where you can find it when you come back and then go off and make the …

But during the vacation, don't be working. Don't be on your computer. Don't be on your cell phone. Don't be planning anything. Just go off and kind of actually have a vacation, which is hard for most entrepreneurs to do. They can't remember when they ever had a day when they didn't work. And that goes back to 12 years old. It's not just when they got into the marketplace. So anyway, and I did it once, I said, Babs and I are going away. I mean, if Babs says we're going on Free Days, we're going on Free Days. But I said, I'll just tell you, this is the list that I wrote up that if I had not gone on Free Days, I would have done all this. This is the list.

And when I came back, I looked at the list, and three or four of the issues had solved themselves when I was away, so I didn't have to solve them, so I didn't have to spend time on it. Then I looked at the list, and although they seemed like crucial issues when I wrote it down, they didn't seem crucial when I got back, so I just said they're not that important. And there were two or three which were really crucial, and I did them in the first three days when I got back, because I was feeling fresh. And then there were three I didn't even understand what it was that I'd wrote it down.

So I said by taking the week off or whatever it was to do it, I had actually gotten an enormous amount of work done and saved myself a lot of bother. Because I was fresh when I came back and when you're fresh—but I said a tightly scheduled entrepreneur cannot transform himself. You know, you just can't transform yourself. You don't have any energy for transformation. You can just keep repeating what you've been doing over and over again.

So one of the things that we've really introduced this whole notion is that constantly have one of the things that grows in your success as a result of your success is the amount of free time you have when you're not working. But as I said, most people want to retire because they want some Free Days. We're going to introduce retirement where you're always working. So Babs and I, you know, we take off the equivalent of about 20 weeks a year every year out of 52. So we work for 32 weeks and we take off 20 weeks and we've done that for 25 years.

Jeffrey Madoff: So before that first time, I was writing down something when you said that and you went through the whole list of this took care of itself, this don't even know what I meant when I wrote it, the filters. Had you ever established filters for what it is you did or didn't do so that on an ongoing basis, you had a criteria for assessing just how important something is to tend to or not?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I've got three filters. The first filter is, can I solve this by doing nothing? And the answer is usually no, you have to do something. And usually the thing you have to do is you have to communicate clearly to somebody else how they're going to do it. Okay, and then the next question is, what's the least I can do to solve this? And that's usually that someone else is currently engaged with what you want it done, or a series of people are. And the third one is, can someone else do the least that I have to do?

But there's a tendency for entrepreneurs to build up the amount of time it takes to get something done when they're tired. If they're not tired and they're fresh, it actually doesn't take very long to do. But since they demand that they be there, you know, that you got to put in the hours, you got to put in the time, their brain brings them down to a low level of productivity. And then they get into a chronic state of semi-exhaustion. You know, I mean, you've been to many business situations where people are not operating at top productivity, top creativity, and everything like that. And so that's the way we do it.

Generally, what this happens, you know, as a result of our time system, that's one of our time systems. We have a lot of different time systems. But one of the time systems is that they don't burn out. And I mean, I have clients, the longest continuous client that I have, that I've seen every quarter, I've seen him every quarter since July of 1987. And he's 72, 73 and top of his game. He runs six marathons every year, you know, and he has no idea of retirement whatsoever. He's just got this activity he loves doing and he's in good shape.

And so it's an interesting, I said, you know, the entrepreneurism, I said, you appreciate, don't you, that when you decide to be an entrepreneur, that it's a life sentence. The life sentence I said, one is that you could never go back to employment. I mean, if you've had a job in the past, you can never go back and do that. But the other thing is they wouldn't have you back. I mean, I'd never hire an entrepreneur as a team member.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. I mean, I think that's true. And I think there's also just a different way of looking at things. If you're an entrepreneur, as opposed to, let's say employee, there's a difference. And I wonder if that difference has changed. I mean, when you and I were growing up, and actually, we're well into our adulthood, there were those careers and job security that just don't exist anymore anywhere. And I wonder if entrepreneurship has also the increase. Is there an increase in entrepreneurship?

Dan Sullivan: No.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I didn't think the numbers had really grown on that.

Dan Sullivan: I mean, I did, when I started the company in ‘74, you know, my first, it was a one person company, but I did it. There was just an accountant that I knew. He wasn't a client, but he was an accountant I knew. I said, is there a way of detecting what percentage of the working population is entrepreneurial? You know, some form of entrepreneurism? In other words, no guaranteed income unless you produce results beforehand. And he said, yeah, he said, I can check. He says, there's IRS statistics, there's ways of looking at this. He says, they're in a different tax category, so you know immediately that they're somewhere else.

And it was 5% in 1974. Last year, I checked again, it was 5%. Pretty steady. And the reason is the world doesn't need any more. It doesn't need any more entrepreneurs. It doesn't need any more entrepreneurs. That's enough. And I'm sure it's different from country to country. And in some countries, they probably have just as many entrepreneurs as another country. But it's illegal. They're criminals.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think the entrepreneurs, you can say there isn't a need for them, but I would say that what entrepreneurs do, if they're successful, is convince the marketplace there is a need.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, but it's not bureaucracies that create new useful things. I mean, there's a need for new useful things. One is that there's a market for new useful things and, you know, somebody is going to take advantage of the opportunity.

Jeffrey Madoff: It's interesting, by the way, when you're talking about these filters and things that you could have other people do and delegation, which is also, I think, a weak point with many entrepreneurs is they don't know how to delegate. They think they're the only ones who can do it right. So they oftentimes have high turnover and everybody's an idiot but them, even though they're the ones that are having trouble every time.

Dan Sullivan: I've been guilty on all accounts.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, well, me too, me too. But, you know, I gained that wisdom by doing that. And the interesting thing about the film production business, the same thing with even when I was manufacturing clothing, you know, designing and manufacturing. And it's true with the play, you know, to use, plug your book, Who Not How, you know, setting up a lighting board, you know, wardrobing, set building. I mean, all of these different things. I know that those skills are necessary. I don't know how to do them, but I trust my taste and know when something is well done.

And so that Who Not How, that's how those businesses operate. Who does that? Because if you try to do everything, you're sunk. And when you're in the kind of business that has a more generalized skill, I think it's easy to convince yourself that only you can do it. And I think that's a big problem.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I mean, and you can go back to you're in your twenties and you've created a fashion company. And one of the things that keeps entrepreneurs small is what happens during the first three years when they're an entrepreneur. I believe that certain things get hardwired in the first three years. And that is there isn't anyone else to do them. And besides, you can't even afford to have anyone else. And so you become the all-purpose problem solver and you pay for it with working nights, working weekends and everything. And you get hardwired. It's like doctors are the unhealthiest people in the world because they go through residency when they're working 80-hour weeks, 90-hour weeks, and they get hardwired to this. It's always gonna be like this. It's always gonna be like this. And so we never take an entrepreneur until they're at least in their fourth year of business.

Jeffrey Madoff: So that, because you have to break down the habit patterns.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, they have to get over that initial period where they're doing everything, you know, and we require a certain income. So, you know, right now it's $200,000. You have to be making more than $200,000 personally to qualify for the Program. Well, if you're in the fourth year of your entrepreneurial career and you're making $200,000, I can guarantee you've solved delegation or you've made great inroads in knowing how to hire. You're not doing that on your own.

I mean, you might be selling drugs or everything else you could make it, but robbing banks or something like that. But there's a certain thing that we look for in terms of success. We're not trying to turn people who aren't entrepreneurs into entrepreneurs. We're not trying to turn mediocre entrepreneurs into good entrepreneurs. We're trying to take people who are already really, really good entrepreneurs into much, much better entrepreneurs.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, now I don't claim to know the coaching world that well, but I've certainly been exposed to a lot of people that call themselves coaches. And one of the things that I wonder about is so many of the people that I've seen that consider themselves to be coaches, they're motivational speakers.

Dan Sullivan: Yep.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yep. Coaching about anything, unless you feel like hearing platitudes constantly is a way to coach people. And the thing that's always struck me about what you're doing is that these are practical applications to learn how to listen to yourself. So you can learn how to solve your problems and tools to help you think about what you're thinking about in order to do so. Is that accurate?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And, you know, over 51 years that I've been doing it myself, and then 36 years, we're in our 36th year of the company. The biggest thing that we show them is how to create a very, very sharp distinction between their work life and their personal life, and that their personal life is getting better and better because of the success of their business life. That's the biggest thing.

And then the other thing is how their role in their own company is getting simpler in terms of the number of activities that they have to do. Okay. And that means teamwork. You have to have a teamwork. And those would be the two things we go after. And I don't think there's another coaching company in the world that actually takes those two approaches.

Jeffrey Madoff: So, yeah, I mean, that's one of the distinctions that I saw that I haven't seen replicated. Is there anything wrong with the notion that I have my business, it does well, I've got sufficient time with my family and friends, things I do outside of work and interests that I have, making enough money to live quite comfortably without having to worry about things, but I'm not amassing a fortune? As opposed to going back to the beginning of this, pushing for constant incremental growth.

Dan Sullivan: I think there's another consideration I'd like to add to what you just said, and those are the getting blindsided by the world. And you have enough reserves as a company. So right now we could go an entire year without making any money and we could keep everybody on staff. And we've worked towards that. It's like a life insurance policy for your company. Because ultimately, banks only want to talk to you when you don't need them. The only time banks want to talk to an entrepreneur where they see an enormous amount of cash flow coming through and the bank isn't getting any of it. Then they want to talk to you. Then they want to talk to you.

So my sense is that in the 50 years that I've been coaching, 51 that I've been coaching personally, we've had seven situations where we could have lost it all. And it really gave me enormous motivation to stockpile cash. Because the big thing is you never want to lose your team.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. Yeah.

Dan Sullivan: So my motivation for growth is to always be able to guarantee that I have my team, which I think is a very worthwhile motivation because otherwise you're always starting over.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. Yeah. Well, what's your take on people that, you know, there's a term serial entrepreneur. Now, there are people that really, you know, to me, it's sort of like the Vegas tables, you know, that they like playing in a lot of different games and the adrenaline of starting something and trying to grow it and oftentimes having to quickly pivot to something else. What is your take on the, I don't know if this is a fair term, but the restless entrepreneur? Because sometimes I think people just give up too easily and too quickly. And then they try to do something else. But there's a sameness is that there is oftentimes a bridge from one to the other is a desperation. And this one better work.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well first of all, there are restless human beings who become entrepreneurs. No, I'm not particularly restless. I mean, we have essentially the same, as far as the company goes, we have exactly the same business model. We have exactly the same target market, you know, for 36 years, it's exactly the same. But I've had a lot of conversations with people, you know, who've gone through, you know, had this business for five years, had another business for five years. And I say, I'm really interested because I don't think that's what you've done. From my perception, I don't think that's exactly what you've done.

My sense is that you've got a base creative company that explores different kinds of products, explores different kinds of presentations. And I says, what if we looked at your career? Because it bothers them, serial entrepreneurs, it bothers them. There's a part of this switching from one thing to another that bothers them, okay? And the thing that bothers them is their reputation. Because to a certain extent, the marketplace likes to see consistency and they like to see continuity. Because they wouldn't want to be in the middle of the project when you decided to stop this business and go do another business.

And it's not just that, first of all, there's a high incidence of what's called attention deficit disorder among entrepreneurs, that they like shiny new things. They like shiny new things. And I would say we have about 3,000 clients, and I would say just based on the way that the medical community or the psychological community looks at ADD, more than 50% of my clients would be on them, you know, would do that. Very different. I mean, some of them, it's high activity, you know, they're very restless. Other words, it's just a very, very busy mind that's exploring different things.

I'm clinically diagnosed with ADD, and I went through three days of testing and there was a psychiatrist who was the coordinator of this whole program. And at the end of the three days, she said, you know, it's kind of funny, she said, because when you filled in your questionnaire, she said, you have to do a questionnaire and you have to fill it in, which immediately screens out probably 80% of the ADD people because they can't complete the questionnaire. She said, sounds like you lead a fairly orderly life. You don't seem to have a lot of stress. And she says, there seems to be a lot of structure in your life and everything else. And she said, but our tests say that you got a 10-ring circus going on inside your brain. She says, it's all over the place. And she says, so what do you do for a living? So I described it. And she said, well, I don't know who else you'd create all these thinking tools for, but you certainly created them for yourself.

Jeffrey Madoff: And don't we ultimately do that?

Dan Sullivan: I think so.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I think it's a natural thing. I think we teach what we want to learn. But if we ever talked about how you actually do what you do, there would be thinking process after thinking process after thinking process that you've developed for yourself to get a handle on new projects, to make sure you know how to put the team together and make sure you know how to do scheduling, what cash flow was like, and you've just worked out. And they're unique to you. They're not something you would learn outside of it. It's through trial and error over 50, 60 years. You've just done all those.

Dan Sullivan: But what I got, and Mike Koenigs is a good example of the serial entrepreneur. He's a good friend of ours. He's a good friend of yours. And I did a podcast with him and I had him go through his first six careers as an entrepreneur. And it's about every five or six years, there's a jump. And I said, what if there is just a single company at the center that just explores new things, develops them and everything else and learns a lot. And then you take that learning and then you jump. And they're all technologically triggered.

Like if you look at Mike's career and we did a public podcast on this. So this is not inside knowledge. This is not secret knowledge. I said, what if you at the center of your company, there's an R&D company. Okay, and that company is just for R&D, research and development, and every five or six years you come up with a great new product and you sell it and you sell it off and then you go back to your R&D company. What if you always have two companies? You have an R&D company and you have a growth company?

So everybody in Strategic Coach operates on that model. They have an R&D company that is always theirs. They own it 100%. And it develops new ideas. It develops new products. It develops new processes and everything else. And then you find ways of selling it and making a lot of money on your R&D. And that's been very relaxing for the serial entrepreneurs.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I want to go back again to the idea of constant growth. And I may have mentioned this example to you before, but I was with this group of people who were just having drinks, and Hamilton was in the early stages, but they were on Broadway already, so it wasn't that early, and it was a staggering hit. And I may have these numbers wrong, but it makes the point. And somebody said to me, said, what do you think Lin-Manuel Miranda is making off this? And at that point, didn't have as many touring companies or anything, but I had read that he was at that time making seven and a half million a year.

And, you know, originally he starred in it, aside from having written it, he starred it too. He played Hamilton. Anyhow, and the guy was a hedge fund guy, says, well, that's not very much money. And I said, I would take seven and a half million he makes over whatever it is you make, if I got to do what he does and I had to do what you do. I'd much rather be doing that. And because at a certain point, what do you need? And I'm not talking about survival, I'm talking about to live a comfortable life.

And I think that a huge part of that comfort comes from once basic things are a given, is fulfillment. This is what I love doing. If somebody offered you five times as much money as you're making, and they said, Dan Sullivan, you would be fantastic. I want you heading up our HR program. You'll find people skills, you can develop tools for that, and you would be great, and we'll pay you five times what you're making at Strategic Coach. Would you think beyond a nanosecond of doing it?

Dan Sullivan: No, because I'm gonna make the five times anyway.

Jeffrey Madoff: And what if you didn't? What if you were pretty much at the level that you're at? And the reason I keep re-asking this is getting to what the drive is behind it. What's the flywheel that keeps it going?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I would say for me, growth is the flywheel, you know, I like growing, you know, I like growing, you know, and some of that shows up on the scoreboard and some of it doesn't, you know, in terms of results, but I'm, it has to do with my relationship that I have, like I have in our top program, which I'm the coach of the top program, the Free Zone. Like, it'll grow this year, we have 110 right now, so 12 months from now, we'll have 130. The year after, we'll have 170. Because we've got the farm club, we've already built the farm clubs with the two lower levels, and they're striving upwards.

And my great thing, and the thing that I find most fascinating, is they get three new tools every quarter, the Free Zone does. They get three new tools. And I go through this period of being really scared. Can I pull it off again? And then I, you know, concentrate and then I do it and I test it. I have these two-hour sessions. I test the tools and I pull it off again. But everything's growing as that's happening. So, you know, the big thing is which I think we've just pulled off and it's been a challenge for 36 years and it's the whole concept. Can you be both contented and ambitious?

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, yeah. Oh, I believe so. Yeah. I mean, I'm ambitious, but I also think that I'm reasonably content in the sense that I'm doing what I want to be doing.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, I'd say you are. The vast majority of entrepreneurs aren't.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, again, that goes back to, and I think it's truly a deep question if you really go into it, is why do you do what you do? You know, and the things that I do, the worlds that that has taken me into, and by the way, it also has been growth. I mean, the play, Personality, each step of the way. And, you know, we made that decision. This is to your point about, you know, having enough money to last a year if something happened and you were able to maintain everybody. I went through that in COVID. You know, and the fact that I was able to keep that creative team together, I am not only proud of that, I'm proud of them and value their commitment to the project.

But it's interesting. And I think the why do you do what you do, a lot of people don't. I think that sometimes the people confuse motion with progress and that there's a lot of wheel spinning that goes on, but the traction isn't really happening or there's a blip and you sort of chase the shiny new thing. And for me, I guess I don't categorize it as growth. I categorize it as I want to be able to keep doing what I'm doing. And that means I've got to have revenue coming in or raising funds coming in for the show or things like that. Because that's just the reality of business and survival.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Well, I think that, you know, for me, why I do what I do, part of the answer is because of who I get to do it with. I just like entrepreneurs. I mean, I've spent my last 50 years just with entrepreneurs, you know, and they're interesting creatures. You know, they're just fascinating creatures. They come in all sizes and all shapes, all kinds of different personalities, all kinds of different capabilities, what they do in the marketplace, you know, spread out over a vast number of different kinds of activities. But there's just an interestingness to the person who just decides that two things, what I love about entrepreneurs, if they've got their heart and mind in the right place, is that they're taking 100% responsibility for their financial security. And the other one is that they know that they don't get any opportunity unless they first create value.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, well, and that's a maxim that you often quote, which I agree with, because I think when you create value, true value, what accompanies that is trust, and when there's trust, you can build a relationship and grow that.

Dan Sullivan: And also that you have the ability to see the world from somebody else's perspective. That you can understand what would be of value to them.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, although it's funny because, you know, with the play, I am looking to satisfy myself and satisfy, because I respect him so much, Sheldon, and satisfy Adam, that we're all a part of something that has meaning. And that's really important. But in terms of the story that we're telling and how we're telling it, there is no compromise in terms of what I think will work. I'm telling the story the way I want to tell it with the people who I think can help tell it the best. And that's what's really important to me about that.

And that's another term that I think is so important. Before we started recording, you and I were talking about some actors, Brad Pitt and Tom Cruise and so on, which is, in order to be good at anything, you have to fully commit. You don't fully commit, ultimately, the structures you're building is gonna be too shaky and will eventually fall under its own weight.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Plus it's not gonna be very good.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. That's right. But I do believe there's an awful lot of people that can maintain what they think is commitment, maybe for 18 months.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I think you tend to hang out with people who are 100% committers, you know, so you've surrounded yourself with people who are 100% committed.

Jeffrey Madoff: To me, those are the only people that are fun to play with.

Dan Sullivan: Well, I know that.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, and so I guess it becomes kind of self-selection. You know, in terms of that, you're going to be attracted to people who recognize and embody the same values, and I think values is also, you know, one of these terms that gets overused, but when you talk about values in terms of creative commitment, respect, collaboration, those kinds of things, and a huge part of that is trust. I mean, Sheldon and I have talked about it, you know, because this project has taken time. It was a year and a half on hold because of COVID.

And then we made a decision, this is going back to what I was going to say before about when you said having enough to survive for a year. We've made the decision each step to make sure we had the reserve funds to make the bridge to the next step. And so as a result of Chicago, we did the showcases in London. As a result of the showcases in London, we're gonna be doing the concerts this October. And so there's been very prudent financial calculation and a strategy to continue and to be able to have to do that, which is a whole thing unto itself, as you know, owning a business.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, so going back to your question that got this podcast going is that I see you as someone who's into growth, constant growth.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and define what you mean by the growth.

Dan Sullivan: You're always growing.

And are you using that intellectually, creatively?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: I put on weight?

Dan Sullivan: You know, you picked out the guy who has the band. I bet there's part of him that's always growing.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. Yeah.

Dan Sullivan: No, I mean, the thing is, the vast majority of what constitutes growth for a person can't be seen from the outside.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right.

Dan Sullivan: Okay. I just finished one of my quarterly books yesterday and it's called Always More Ambitious. And I said, you know, ambition is really an interesting word because it's history. If you look at history, how it gets talked about ambition. Two things, it's kind of like a dangerous word and it's sort of like a dirty word. You know, it's kind of like a dirty word, you know, ambition and that people who are really ambitious, they say, well, you know, you got to be watching out that you're not too ambitious because people don't like people who are too ambitious and everything else.

And I said, you know, I got a feeling, you know, and if you look through history, it's generally, I would say, depicted as somewhat bad, ambitious, you know, I mean, if you go to Shakespeare, like the tragedies, it's the ambition that creates the tragedy in many of the cases. You know, in his history plays, it's ambition that's the key thing. And my sense is, and I really noticed, so, you know, in the years of coaching entrepreneurs, there's a real big difference between male entrepreneurs and female entrepreneurs. And what I've noticed is that female entrepreneurs at a certain point have to justify why they're still more ambitious. Male entrepreneurs have to justify why they're not more ambitious.

Jeffrey Madoff: And why do you think that is?

Dan Sullivan: Well, it's the gender, it's the different roles that women played in history up until recently, and the roles that men play. You want a really ambitious man because that's important, but women should only be ambitious in their role as women, which up until recently was in the home.

Jeffrey Madoff: As defined by men.

Dan Sullivan: Well, as defined by what was required to hold society together. You know, I mean, I don't believe in this, you know, that all of life happened because of the relationship between men and women. I mean, somebody saying that men determine this, but also it's true that men are expendable and women are not. That's part of the society we lived in, you know, that women and children got in the lifeboats, the men went down, you know.

Jeffrey Madoff: But I would say, though, about ambition, ambition is the key to drama. Somebody wants something. What are they willing to do to get it? Or what kind of fire trial do they have to go through to accomplish what their goal is? And so ambition is very much a part of the makeup of theater and film and books and so on. And I think that there's blind ambition, which purports to mean you will overcome anything that gets in your way, no matter what the emotional cost is or whatever.

But I would say that You can't be a successful entrepreneur without ambition. And even if your ambition is just to provide for your family, which is no small thing, I mean, ambition is, to me, that can become corrupted, but it is an energy force that moves you forward towards what it is you want. And if there's collateral damage as a result of expressing that, that's something that needs to be looked at. But I don't see ambition in and of itself as negative at all.

Dan Sullivan: But when I was talking to the entrepreneurs, I say, you know, if I go back and think about all the ambition conversations in my life, first of all, it's unequal. The people have unequal amounts of ambition. Okay. And the way I said, it's sort of pictured that when you're born, you're given an ambition tank. It's like a gas tank. You get an ambition. And some people just have little ambition tanks and some people have big ambition tanks. And the other thing is it's filled up at birth, but then throughout life, you know, the tank goes dry and there's a certain point where you're going to run out of ambition.

I'm just saying how I think it's generally described, you know. And I said, my sense is ambition is the capability that produces all other capabilities. It's a capability. It's a platform that allows other capabilities to develop. And that it's actually a muscle. It's not a gas tank. It's not a tank. It's a muscle. And the more you use your ambition to test out, to create new capabilities, the more the ambition grows.

Jeffrey Madoff: And I guess I would add to that, in the definition you're stating, is there's a fine line between ambition and desire, and the difference is that ambition is more active. But desire can be, and I think desire can morph into ambition.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. For example, I'm a lot more ambitious at 81 than I was at 51.

Jeffrey Madoff: And why do you think that is?

Dan Sullivan: Immensely more teamwork and collaboration. I just have access to capabilities at 81 that I didn't have at 51.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. Good point. Good point. So there are things that you're in a position to do that you weren't in a position to do back then. You know, which is also interesting because that takes us back to the growth of the business, but it also is a good example of the desire that turns more active, and I'd say more active desire is ambition, whether it's to build a company, create and manifest a new idea, or whatever. And I'm not exactly sure what that crossover point is, because I haven't said it before, but I do think there's an interesting transition point that happens between desire. A lot of people want to do things, they just don't, you know, because it either takes too much work, they don't have the discipline to do it, they don't know how to do it, whatever it is. But when that ambition, like my ambition to do this play, you know, you don't let ignorance stop you. You learn.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. But my sense is you didn't approach this any different than you've approached any new thing in your life.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's correct. Yeah. That's correct.

Dan Sullivan: I mean, this just shows up when you're in your late sixties as a result of everything else you did before that. I mean, you know how to create a production. You've been creating production. This is another kind of production.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right.

Dan Sullivan: You have a production-creating capability.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, and the thing about it is, is that recognizing and coming up with the story, and that where my desire to tell that story turned into the ambition to manifest it as a play. And then all the stuff that goes along with that. That's what you get when you basically go into different businesses, whether it's fashion design, film production, teaching, or whatever. It's when you don't know something. You know, I always approach those, I mean, my approach has matured because I know how to read the signs a lot better than I did when I was younger.

Dan Sullivan: Well, you have enormous higher levels of discernment now.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I hope so.

Dan Sullivan: No, no, you do. I mean, I've been more or less on this particular project's history with you. I mean, more or less from the beginning. And, you know, my sense here, first of all, you know incredibly amount more about what the theater world, what is and is not possible right now than you did when we had lunch, where you first introduced the project and told us about the project. I mean, your know-how about this world has gone through the roof. Which is also survival.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, it's also pleasurable.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, yeah. Yeah, it is. Nothing greater than knowing more.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, well, and the thing is, it's both an end in itself and it's never ending. That desire to want to know more, to learn more, you know, I think those are desires that have turned into ambitions for me. I think for you too, I think it's fair to say.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. I just don't see it ever stopping. For either one of us.

Jeffrey Madoff: No, I agree.

Dan Sullivan: And I'm doing my best, and I think you are, too. We're doing our best not to give death any assistance.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. Yes.

Dan Sullivan: You know, death is good at what it does, you know. It doesn't spin around. But I do know death goes for low-hanging fruit.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, don't give it any assistance. That's for damn sure. That's right. Yeah, it's all quite fascinating. You know, my wife just went through this knee surgery and her doctor told us the aftermath of knee surgery, it's one of the most painful experiences you'll ever have. And, you know, after second or third week, it backs off somewhat. But initially, you're going to have to make yourself do these exercises, which you're not going to want to do with a physical therapist who will be coming over, because it just hurts so much, you know, that you don't want to do it. But if you don't do it, you aren't going to get the long-term payoff of full range of motion in a mobile joint.

And Margaret has that kind of discipline that she can make herself do it even though she's crying during it because it hurts so much. And it's just, there is a desire to get beyond the pain, which needs to manifest itself in the ambition to make sure that you do the physical therapy. Because if you don't, as much as you don't wanna do it, if you don't, you're not gonna reach the goal that you have. And in a way, that's like life, you reach painful points and you gotta figure out, am I gonna get through to the other side of this? And getting through that other side is sometimes tough, but the overarching thing is progress and growth, like what you were talking about before.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, the knee is the one place in the body that takes the most pressure. Yeah. Oh, stress and pressure. The knee gets it all.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. The knee in your brain that takes the stress, gets the stress too.

Dan Sullivan: The one you can get a replacement for. That's true.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. Look at what Frankenstein did. You know, tried to replace that brain and screwed it up. Where'd you get? What'd they get?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. We've been yakking away here for an hour.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think I got a lot. I think that I had never thought before about that distinction between desire and ambition and the nuances to the term growth. Because, you know, it depends on what your metric is. So I think that those are all incredibly meaningful, you know, and those distinctions and those nuances, because I think the deeper you dig, the more you can understand about yourself and ultimately about others.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. I will say this, I think there's been a big growth of opportunity in the world since you and I were born in the 40s for being ambitious and growing in different ways. I think that the number of different things that you can do in this world has expanded enormously since the 1940s.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, it would be interesting to do sort of a survey of just, you know, what that is, or is it that as we ascended and traveled through our lives, the people we met, the opportunities we had and all that, you know, an opportunity is not an opportunity if you don't recognize it as one.

Dan Sullivan: But for example, when I was growing up during the ‘50s and ‘60s and early ‘70s, there was no such thing as entrepreneurial coaching. And now you can be an entrepreneurial coach. I mean, there's hundreds of them. I would say in our program, we have 50 or 60 entrepreneurial coaches who they're getting dollars that could have come to me. And I said, it's a big world, you know? You know, I've got 3,000, but there's a lot more than 3,000, so somebody should get to them. I think the possibility for creating new forms of value is much greater today than it was in the 1940s and ‘50s.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, that could be an interesting thing to do a future dive in. There are jobs that have gone away, and there are jobs that didn't exist before. And I think we have seen a world that has changed, and I think that's true in all different eras, but it would be interesting to see, because starting with television in the ‘40s, telephones and personal computers, and nobody was doing coding. You know, very few were doing coding until World War II.

Dan Sullivan: And hardly anybody's going to be doing coding from this point forward.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, well, because so much more has become plug and play, too.

Dan Sullivan: It's automated.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. Yeah, there's a lot. That'd be fun to sort of look into what has disappeared and what's come back.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, it's a really, really interesting thing. The uniqueness that I'm seeing of the way our entrepreneurs are developing their markets, there's just a tremendous uniqueness about it. They're not following best practices. They're creating their own practices.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I think what best practices are, the fundamentals, I don't know, have changed, but the day-to-day manifestation certainly has.

Dan Sullivan: I mean, one that hasn't changed, you should have more coming in than going out. Begin a business. That comes as close to a law of physics that I know, yeah. Anyway, I got a lot out of this, your question and everything else, because we're working on a model right now, and well, first of all, I'm gonna be seeing you Sunday of next week.

Jeffrey Madoff: You are, for a podcast.

Dan Sullivan: No, I'm gonna be seeing you for brunch.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right, but that's on the third, isn't it?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, on the third.

Jeffrey Madoff: So that is a week from Sunday.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, not this Sunday, but the next Sunday after that.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. Yeah. So great. That's great.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. In the flesh. I mean, it's almost like real.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes, we'll get to three dimensions. Yeah, because last I saw you, it's easy to remember because it was for your 80th birthday party.

Dan Sullivan: Right. Which was a blast. That whole trip was so much fun. That was great. So, yeah, this is this has been, I think, a very worthwhile exploration. Thanks for joining us today on our show, Anything and Everything. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend. For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

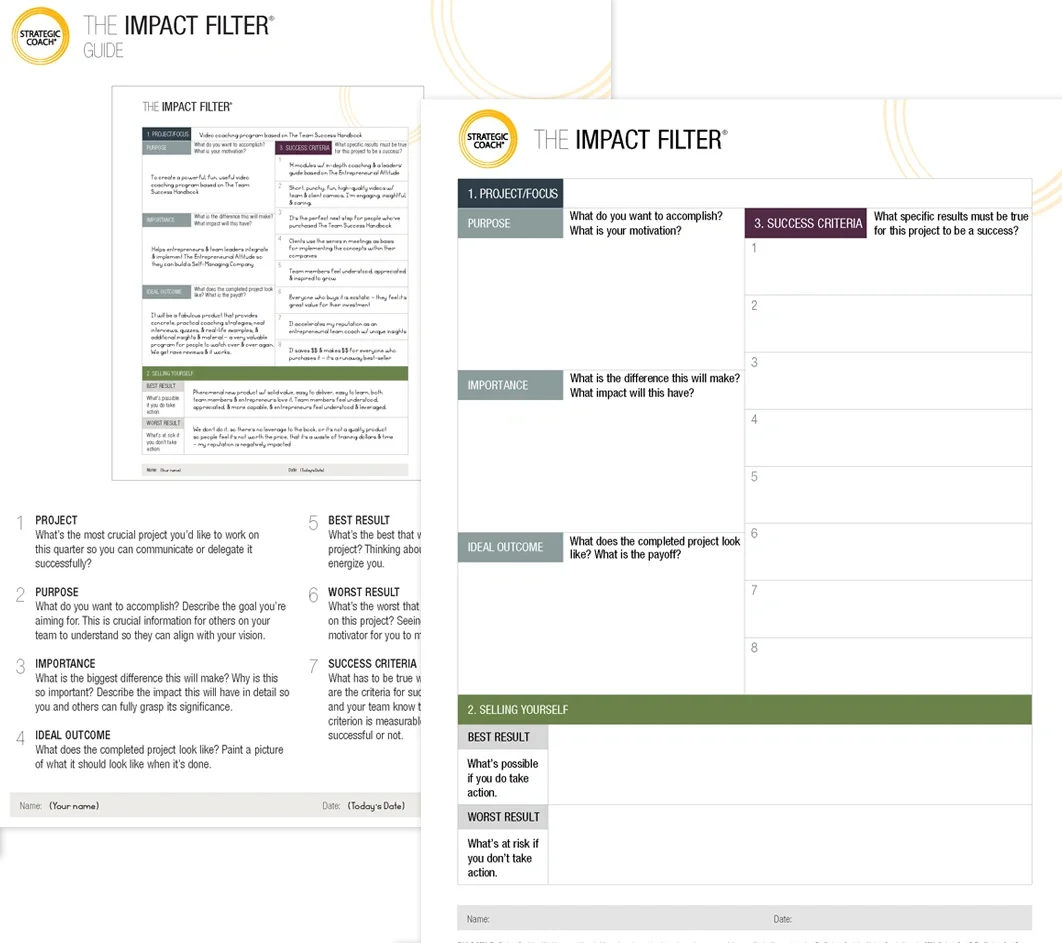

The Impact Filter®

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.